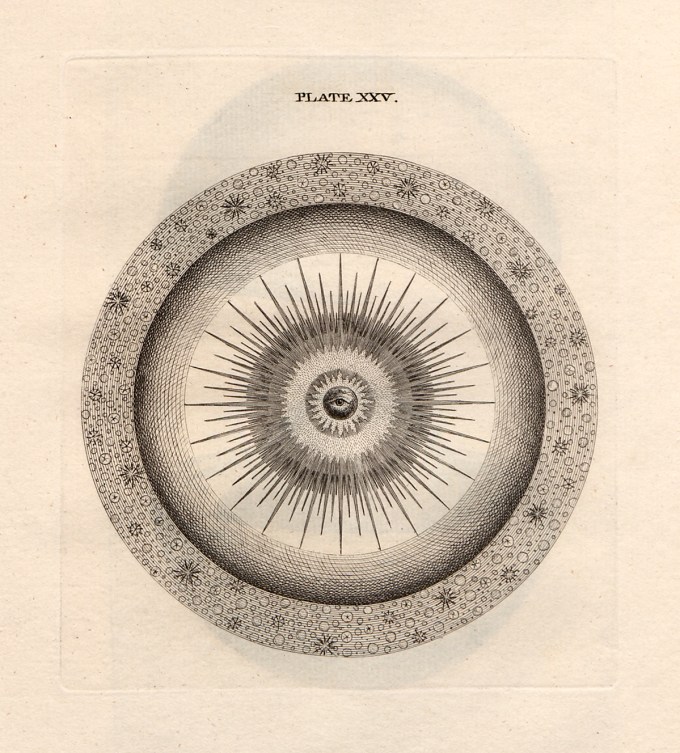

Because it is its own place, it can only perceive the rest of reality from that place: Our entire view of the world, including the recognition of otherness, is lensed through our own particular mind, ground into shape by its particular genetic inheritance, smudged by its particular life-experience. Everything we see — ourselves, each other, the universe itself — is focused into meaning by that lens.

In all of this, a paradox: A mind as complex and highly organized ours can perceive the fact of other minds, even more different from our own than the bodies they govern — an awareness haunted by Iris Murdoch’s reminder that the tragic freedom of our experience is the recognition that “others are, to an extent we never cease discovering, different from ourselves.” And yet the human mind is governed by a single organizing principle — self-reference, known often by its other names: memory, language, love.

At the fifth annual Universe in Verse — which explored through the dual lens of science and poetry the ultimate question animating these atoms with consciousness: What is life? — Frost’s poem came alive in a lovely reading by cognitive scientist Alexandra Horowitz — director of the Dog Cognition Lab at Barnard College, writer of some uncommonly poetic books about how canine minds see the world, creator and host of the wonderful new podcast Off Leash. She prefaced her reading with a poignant reflection on the limits of consciousness lensed through a point of view:

ON LOOKING UP BY CHANCE AT THE CONSTELLATIONS

by Robert Frost

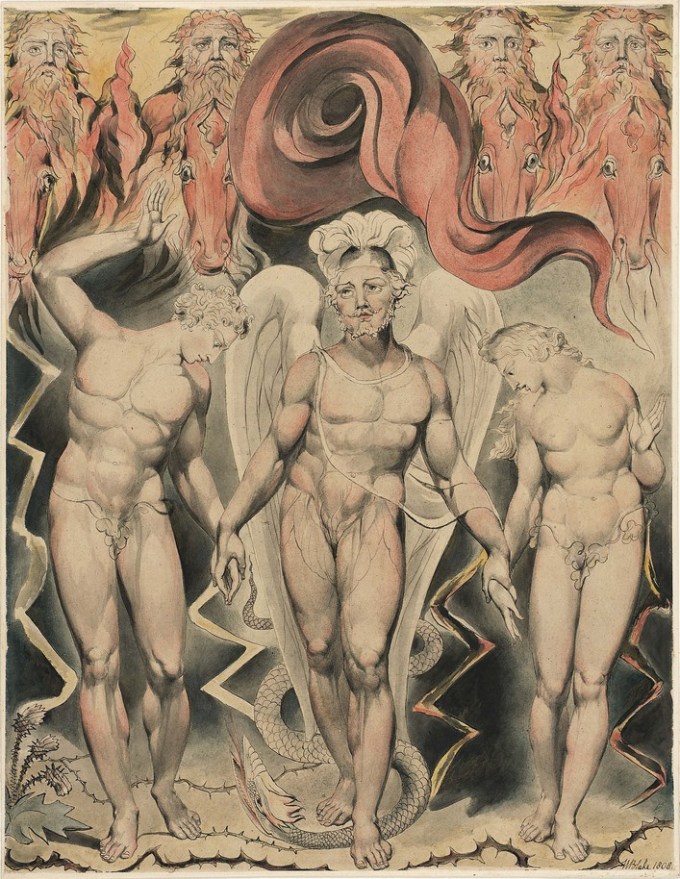

The mind is its own place, and in it self

Can make a Heav’n of Hell, a Hell of Heav’n.

The first English use of the word space to connote the cosmic expanse appears in line 650 of Book I of Milton’s Paradise Lost:

You’ll wait a long, long time for anything much

To happen in heaven beyond the floats of cloud

And the Northern Lights that run like tingling nerves.

The sun and moon get crossed, but they never touch,

Nor strike out fire from each other nor crash out loud.

The planets seem to interfere in their curves —

But nothing ever happens, no harm is done.

We may as well go patiently on with our life,

And look elsewhere than to stars and moon and sun

For the shocks and changes we need to keep us sane.

It is true the longest drout will end in rain,

The longest peace in China will end in strife.

Still it wouldn’t reward the watcher to stay awake

In hopes of seeing the calm of heaven break

On his particular time and personal sight.

That calm seems certainly safe to last to-night.

On this world, space has produced “atoms with consciousness,” in the lovely phrase of the later poet Richard Feynman. Minds. A world rife with minds, as various as they are numerous.

Space may produce new Worlds; whereof so rife.

Complement with Rebecca Solnit’s splendid reading of and reflection on the century-old poem “Trees at Night” from the same show, then revisit this rare recording of JFK’s tribute to Robert Frost — which is at heart a manifesto for the power of art to clarify, sanctify, and defend truth.

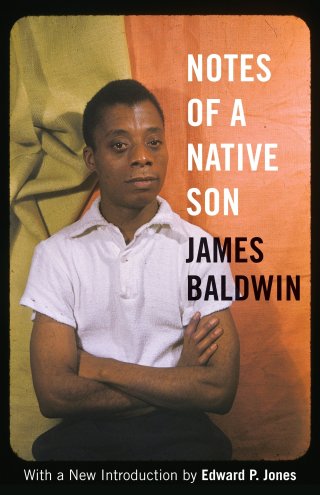

An epoch of lens-clearing after Milton, as we discovered that the universe is wildly larger than we thought and that our own world is wild with other consciousnesses, Robert Frost (March 26, 1874–January 29, 1963) took up this subject with great subtlety and splendor in his poem “On Looking Up by Chance at the Constellations.”

Elsewhere in his seventeenth-century epic of philosophy in blank verse, Milton formulated the quintessence of human experience:

Milton lived through a turning point in human thought — an era that cleared the inner lens into a discomposing glimpse of reality as Galileo turned the lens of his primitive telescope outward to dismantle our illusions of centrality, our puerile cosmic self-reference. By the time Milton visited Galileo, he was too old and blind to look through the astronomer’s telescope and marvel at its concrete revelations of other moons spinning around other worlds spinning around a shared star. But he saw the abstract truth beyond it: The universe is rife with otherness, every point of light a point of view.