Most of us who went into philosophy didn’t know all that much about what it was; we learned via example and ostension: this, these texts, the writings and ideas of these people, is philosophy. We have been told various things to justify this particular set of people, these starting points and texts. But often what we were told is just something said on the first day or two of class, not rigorously questioned or challenged even by those telling us the story. We are all, after all, mostly philosophers, interested in philosophy, not intellectual historians, interested in intellectual history. Once we have some interesting philosophy in front of us, we might not be inclined to ask all that many questions about what we haven’t been shown and why.

This is the kind of scolding reason. It’s also a problem: none of us like to be told that we have to do anything. That’s why we got into philosophy! It’s also a disaster! Because—in my experience—every person I’ve seen encounter ideas and arguments and thought experiments from these other traditions finds something there to be excited about. There’s something for everyone, whether one works in ethics, epistemology, metaphysics, mind, language, political, social, logic, or anything else.

But another key part of the story is just a story of cycles of ignorance: your teachers don’t know about X, so they don’t teach you about X, so you don’t know about X, so when you teach you don’t teach about X, so your students don’t know about X… It might be that what falls under ‘X’ is a result of racism and sexism. It might also just be a matter of what is easily accessible at a particular time and place. We live at a time of unprecedented access to texts, ideas, and traditions from throughout history and from around the world, in addition to sophisticated scholarly commentary on and distillation of all those texts, ideas, and traditions.

To Be a Department of Philosophy

by Alexander Guerrero

Bryan Van Norden has put together a remarkable bibliography of readings on Africana, Chinese, Christian, Indian, Indigenous, Islamic, Jewish, and Latin American philosophy, including many helpful suggestions under the heading ‘Where Should I Start?’ for each of these areas.

A somewhat less obvious step, but one that I think deserves more consideration and discussion, is to hire (at adequate compensation) experts from other institutions to teach mini-courses, give lectures, and perhaps serve as outside advisors for students at one’s institution.

There is now a remarkable collection of syllabi collected by the American Philosophical Association on topics in all of these areas. These are excellent for making it easy on new instructors, so that you don’t have to start from scratch.

And for those of us interested in philosophical ideas, there is a more basic kind of excitement: meeting something new and beautiful and possibly bewildering that helps you understand something you are fascinated by and care about.

COMMENTS POLICY

This story of philosophy has been overwhelmingly male, overwhelmingly white, and, as Garfield and Van Norden are at pains to point out, overwhelmingly Anglo-European, dominated by Europe, the UK, and, joining later, the United States. Why is this the story that has been told, over and over again, to undergraduates moving through philosophy programs? Why is this the story that we continue to tell through our major requirements and PhD distribution requirements?

Obviously, there are tens of thousands more students learning philosophy at an undergraduate level than at a graduate level. But if departments of philosophy are ever going to change the story they tell at any kind of scale, it will need to be through making it easier to get a PhD in Philosophy while also working on philosophy from outside the standard story. This is also vital for creating philosophers who can work on these philosophical ideas and traditions as researchers, bring them into conversation with other philosophical work, and do so at a high level of sophistication and competence, learning the relevant languages, and so on.

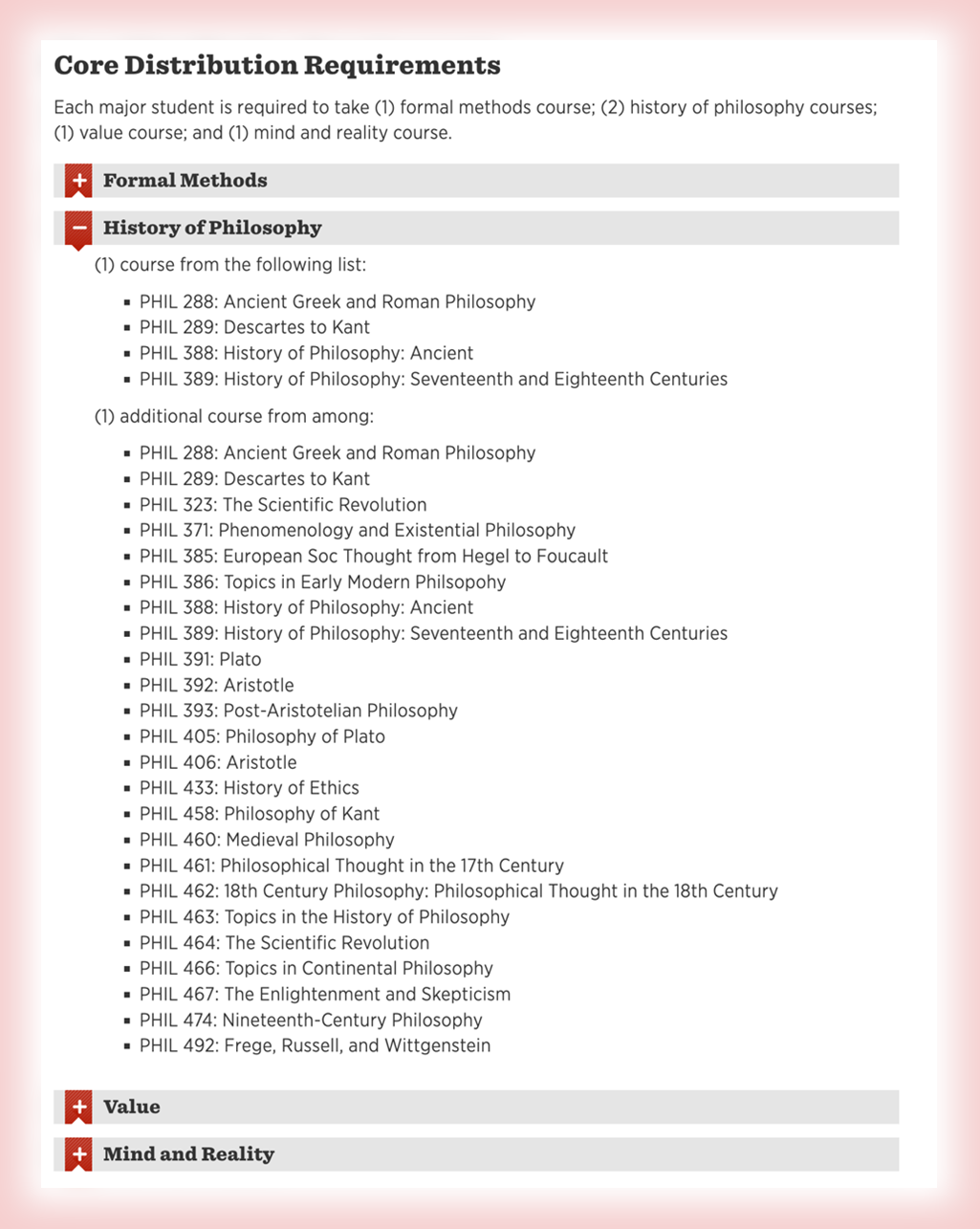

At many institutions, the Philosophy major is structured so that philosophy majors have to take something like 11 or 12 total philosophy courses, with 1 course in Logic, 1 course in Ancient or Medieval Philosophy, 1 course in Modern Philosophy, 2 courses in Metaphysics, Epistemology, or Language, 1 course in Moral or Political Philosophy, and then 5 or 6 electives, spread out over courses at varying levels. This is the basic pattern at Rutgers, Penn, and NYU (the three philosophy departments that I have spent the most time in, but also three pretty different institutions), but it is also similar to some places that have specialists on the Philosophy faculty who work on topics outside the standard story, like Michigan. Often, there is a list of courses on historical topics that specifies which courses can count as fulfilling the requirement, and that list almost always leaves off courses that aren’t part of the standard story. At Michigan, for example, these are the courses that count for history:

An additional obvious next step is to actually hire people who are experts and specialists on philosophy from outside the standard story. That’s not always possible, of course, but when one sits around in a department meeting thinking about what holes there are in the current program coverage, one should start to take these holes more seriously.

At many institutions, it is not very difficult to get a new course on the books. In my experience, it was very easy to get institutional approval for a new course on African, Latin American, and Native American Philosophy. (You can read about my experience in that regard.) Most departments at most institutions are already way ahead of Philosophy in expanding the story they present to students, and administrators are excited when this happens. My philosophy colleagues have always been nothing but supportive in this regard. I expect yours will be, too.

This kind of answer requires (a) that there is some kind of meta-philosophical view for sorting things as ‘philosophy’ or not, (b) that it is an attractive, non-question-begging meta-philosophical view, (c) that those telling this standard story agree on this view and use it to sort work into the ‘philosophy’ basket or not, (d) that this view compels us to include what we teach and require but exclude what we don’t currently cover, and (e) that this sorting just happens to include only Anglo-European work and almost nothing from non-Anglo-Europeans prior to 1950 or 1960 or something like that (at which point Jaegwon Kim and a few others get to become the very first non-Anglo-Europeans ever to do philosophy!). (Or perhaps there isn’t just one meta-philosophical view that all agree on, but, by amazing coincidence, the various meta-philosophical views are all such that they get extensionally equivalent results regarding (d) and (e)?) That is already quite a lot to swallow. I know that, at least in the places I’ve been, I would not expect any kind of broad meta-philosophical agreement, nor has there been any recent sorting or meta-philosophical discussion. What would the meta-philosophical view be? Something about arguments? Arguments about certain topics? Counterexamples—from inside and outside our standard story—abound. Garfield and Van Norden offer many of these.

The Center for New Narratives in Philosophy, directed by Christia Mercer, is creating events and other resources aimed at bringing work from outside of the standard story into view. This includes a book series, the Oxford New Histories of Philosophy (co-edited with Melvin Rogers), which brings both primary texts and secondary materials helping to make accessible and “available, often for the first time, ideas and works by women, people of color, and movements in philosophy’s past that were groundbreaking in their day but left out of traditional accounts.”

Related: When Someone Suggests Expanding the Canon, Philosophical Diversity in U.S. Philosophy Departments, End Philosophical Protectionism, Two Models for Expanding The Canon, Bad Arguments Against Teaching Chinese Philosophy, Why Don’t We Study African Philosophy?

Of course, to do work in these areas in a serious way will be hard (even if not impossible) to do without more direct expert advising. And there are very few people teaching in Philosophy PhD programs who are experts in these areas. This is not a trivial problem, given the current composition of faculty at most PhD programs in North America, the UK, Australia, etc. Most such faculties include no one who can advise a dissertation on these topics or traditions. (To find those that can, or to find potential experts to consult, you might look to The Pluralist Guide for some of these areas, or to the discussion on Warp, Weft, and Way concerning graduate programs in Chinese Philosophy.) And although departments could hire away experts from some of the other institutions out there, this won’t address the overall numbers problem. (It still might be an important signal to the profession if more ‘fancy’ PhD programs were to do this.)

Perhaps the single-most remarkable resource, The History of Philosophy Without Any Gaps project, now has extensive coverage of Islamic Philosophy, Indian Philosophy, and African Philosophy, thanks to the truly amazing work of Peter Adamson, Jonardon Ganeri, and Chike Jeffers, among others. The future plan includes coverage of ancient China with the help of Karyn Lai. It is helpfully organized chronologically but also indexed thematically, so that one could learn just about aesthetics or ethics or mereology.

And it’s not surprising that it is exciting. It provides a new dimension of interest and even a kind of validation to see that people in considerably different sociohistorical circumstances might have also been thinking about some of the same things that keep you up at night. Comparative philosophy, whether across history or cultural difference or both, is tricky, and it is easy to be too quick to see commonality even when the reality might be more complicated. But it is undeniable that there are many common questions and concerns, and many interestingly different and interestingly similar ideas and arguments.

But, even more decisively, we can tell that this isn’t what is really going on, because of the second difficulty with this answer: those who endorse it have either no or only glancing acquaintance with work from these other traditions, so the actual explanation for inclusion or exclusion can’t be some faithful, careful application of an attractive meta-philosophical principle. Nor can we defer to our wise forefathers (and they were certainly almost all men) who first crafted this story by using some (now forgotten) beautiful meta-philosophical sorting principle. We might not know that much about them, but one of the things we do know is that they, too, knew very little about any work that isn’t part of the standard story.

As some of the foregoing suggestions indicate, there are things that people should do even if they can’t bring experts in these areas into faculty roles in their department. But that is obviously an excellent thing to do if it is a possibility. Just as it is impossible for most graduate programs to be excellent in their coverage of every single area of even the standard story, it won’t be possible for graduate programs to cover all of these areas and philosophers. But departments can develop specializations and strengths in some of them, and if some of those are outside the standard story, that will do quite a lot to change the perception of the department and the field.

(1) Continue Your Philosophical Education

Fortunately, one thing that is changing significantly are the resources available to people for their own continuing philosophical education with respect to work from outside the standard story.

For some significant part of that time, many of those doing the pointing have plausibly had biases against work by women and work by non-White people. Racism and sexism are part of the story of exclusion.

Those parts of the explanation suggest good news and concrete steps for the project of beginning to tell a different story. I will suggest six such steps, concerning both undergraduate and graduate philosophical education. These might not all be equally easy to implement, depending on one’s particular local situation. But I hope that many of them can be taken up by those involved with philosophical education in almost any educational setting.

There is a new program, the Northeast Workshop to Learn About Multicultural Philosophy (‘NEWLAMP’), which has this as its central purpose. Twenty philosophy instructors from across the country will meet in July to expand their knowledge of African and African social and political philosophy. Future iterations will cover different traditions and topics. More such programs should be created.

Once you have identified courses being offered at your institution that expand the standard story, or once you and your colleagues have increased your knowledge and created such courses, start requiring your undergraduate and graduate students to take these courses.

Once you have identified what is already offered at your institution, think about what isn’t being covered, even if those courses are brought also into philosophy, and learn enough to create introductory courses on that topic or to bring that material into existing courses. This is actually one of the best ways to take up the first suggestion, as nothing helps one learn a topic more than teaching it.

“There are many reasons to expand the story we tell about philosophy. But a main reason is just that the best, most interesting, and even the correct answers to philosophical questions that interest us might be found anywhere.”

An initial, somewhat modest set of steps is to encourage MA and PhD students to take up the first suggestion, learning about philosophical work from outside the standard story in an area that is an AOS or an AOC. They might do this via directed reading groups, teaching their own courses on these topics or TA-ing for courses that faculty teach, or other mechanisms from your program that help to provide both time and support for those doing this. This has obvious non-instrumental benefits, but there also now is a significant demand for new faculty with competence or expertise in these areas. As Marcus Arvan documents, the number of jobs in ‘Non-Western’ Philosophy was roughly half what it was for all of Mind, Language, Metaphysics, Epistemology, and Logic combined. Developing an AOS or even an AOC in these areas might really help students on the job market.

The following is a guest post* by Alexander Guerrero, Professor of Philosophy at Rutgers University. It is the second in a series of weekly guest posts by different authors at Daily Nous this summer.

The main answer to this is a human one: it’s natural to feel defensive and protective of what you have come to know and love. The vital point—at least by my lights—is that the problem with the standard story isn’t what it includes: what we all have come to know and love is, in many deep ways, important and beautiful. It makes sense that we want it to be taught and studied forever. The problem with the standard story is entirely about what it excludes. Figuring out how to move forward, figuring out how to begin telling a different, broader story, requires looking backward to better understand these patterns of exclusion. The second kind of answer to the ‘why this story’ question—the debunking and historicizing answer—helps us in that regard.

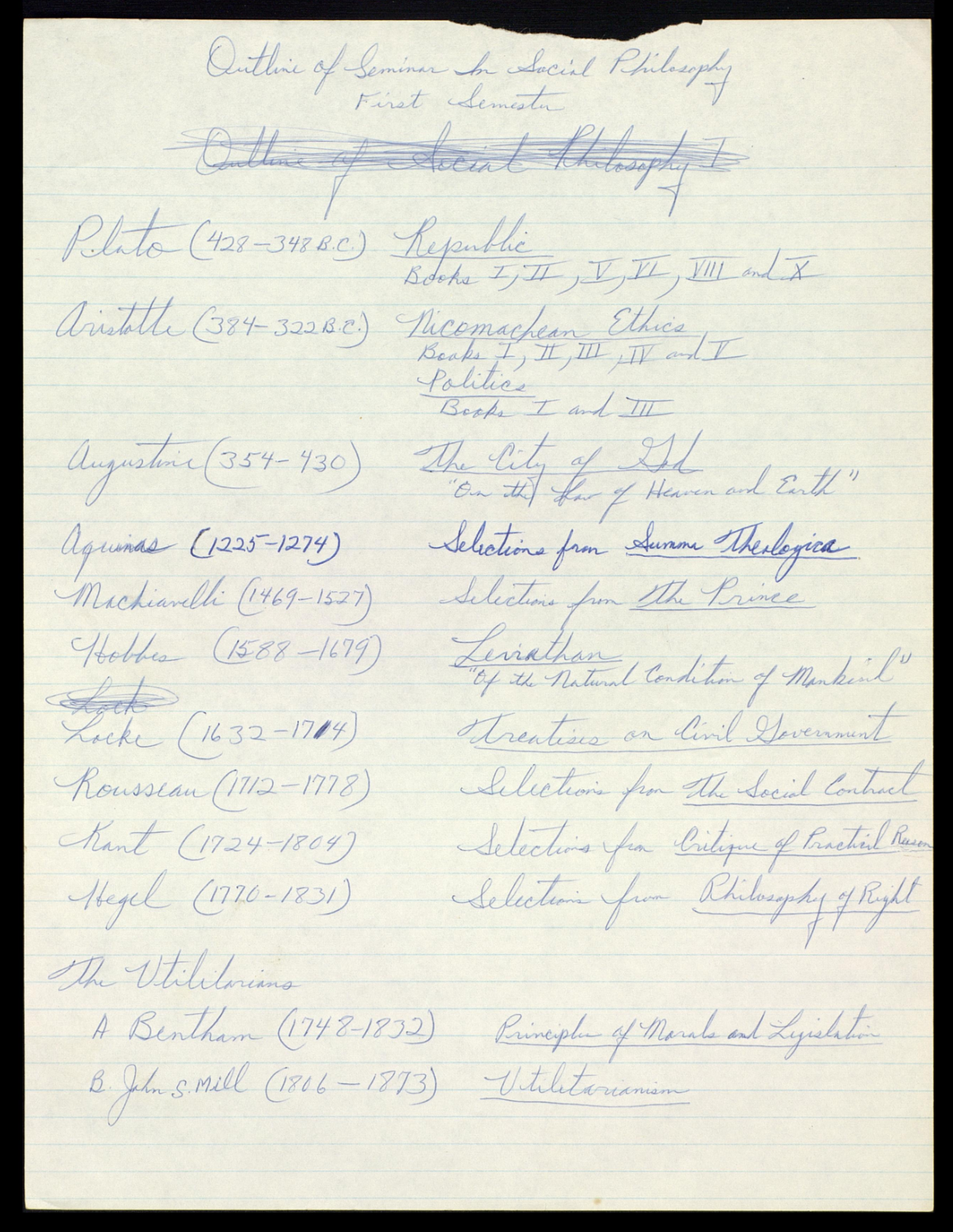

Martin Luther King, Jr.’s outline for his social philosophy seminar at Morehouse College

Given that many are very attached to everything currently required as part of the standard story, an easy initial recommendation would be to add in an additional requirement for a course from one of these other traditions, once those courses are being offered regularly enough at one’s institution. Prior to that, I would suggest pushing so that they can count as alternative ways of fulfilling existing requirements, but I know that is likely to engender more controversy.

To address this concern, an obvious initial step is to look within one’s institution, as suggested above, to see if there is expertise on these philosophical topics outside of the philosophy department.

(2) Make Connections at Your Institution

The profession of philosophy and the education of philosophy students—at both the undergraduate and graduate level—must change.

(3) Create Courses to Expand Your Department’s Story About Philosophy

If you think there are better and worse answers to philosophical questions, or even correct and incorrect answers to them, some worries emerge with the dominance of the standard story. The “streetlight effect” is the name of a kind of observational or investigational bias that occurs when people are searching for something but look only where it is easiest, rather than all the places where the thing might be (based on a story of a drunk person looking under the streetlight for his keys, even when he is pretty sure he left them in the enshadowed park across the street).

The first is already obvious, I would expect: if one of the main reasons we tell the story we do through our philosophy curriculum and requirements is simply historical racism, we should do something about that. Continuing to do nothing, to just run out the exact same philosophy curriculum and to produce students with the exact same limited understanding of philosophy, is to both be complicit in that racism and to perpetuate it. Perhaps one thinks that racism plays very little role in the initial crafting of the story; it was, instead, just that people taught what they knew about and what was available to them. That just makes us doing nothing all the worse. It is then our racism—or culpable negligence, or something close to that—that is keeping the story alive. Because work from all these traditions is, at this point, relatively easily available to us.

But there are also many things one can use on one’s own, or in a small reading group. Last Spring, I ran a reading group on African, Latin American, and Native American philosophy over Zoom. This was very fun and relatively easy to do. All the readings and plan are available here, and many other similar groups could be organized, covering all manner of topics.

To be a department of philosophy, we must change the story we are telling.

(4) Change the Official Story Your Department Tells – Undergraduate Level

There are familiar arguments that racism is inefficient: by only considering people from one racial group for hiring, for example, one narrows one’s search in an arbitrary way, missing out on brilliance and ability for no good reason. Here, too, in the quest for philosophical truth, racism is inefficient.

Familiar resources, like the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy and Philosophy Compass, are significantly expanding their coverage of philosophical work from outside the Anglo-European tradition. For example, Guillermo Hurtado and Robert Eli Sanchez have created a remarkable overview entry for the SEP on Philosophy in Mexico, there is a fantastic entry on metaphilosophical questions concerning ‘Latin American Philosophy’ authored by Susana Nuccetelli, and Stephanie Rivera Berruz has written a brilliant entry on Latin American Feminism. Philosophy Compass has new Section Areas on African and African Philosophy, Indian Philosophy, Latinx and Latin American Philosophy, and Native American and Indigenous Philosophy, to accompany the longstanding Section on Chinese Philosophy. Keep an eye out for articles that will helpful both for professors looking to get their bearings and for assigning to students. Also, check out The Philosophical Forum, as Alexus McLeod (a world expert on several different philosophical traditions from outside the standard story) has been brought on as the new Editor of that journal, and he aims to make it a leading forum for work from all philosophical traditions.

Very little has changed in this regard in the past six years. There are excellent people working in these areas, but there are simply not yet enough people who are experts in these areas, and the vast majority of PhD programs in Philosophy are not producing people who work or teach in these areas.

[Gaba Meschac – Globallon (detail)]

The second answer to our initial question of why this is the story of philosophy that we offer focuses on historical factors, explaining why we are in this situation without purporting to justify it. The long version of this story would need to be told by someone with more knowledge and historical and sociological expertise than I have. Randall Collins, in his unbelievably comprehensive masterpiece, The Sociology of Philosophies: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change, tells some relevant parts of this story, focusing on the shift of philosophy into universities, particular networks of philosophers and intellectuals and the stories they tell about their own origins, and the gradual accumulation and ossification of a story as generations of students encounter it and learn about the key figures within that story (and, just as importantly, do not learn about other things).

The vast majority of philosophy departments in the United States offer courses only on philosophy derived from Europe and the English-speaking world. For example, of the 118 doctoral programs in philosophy in the United States and Canada, only 10 percent have a specialist in Chinese philosophy as part of their regular faculty. Most philosophy departments also offer no courses on Africana, Indian, Islamic, Jewish, Latin American, Native American or other non-European traditions. Indeed, of the top 50 philosophy doctoral programs in the English-speaking world, only 15 percent have any regular faculty members who teach any non-Western philosophy.

The first kind of answer makes a substantive claim about philosophy. It claims that, in sticking to the story above, we teach and require everything that is most centrally well-described as philosophy. We leave out, or put to the margins, work that is just religion, or anthropology, or literature, or cultural studies, or “thought” that doesn’t constitute philosophy.

(5) Change the Official Story Your Department Tells – Graduate Level

I’m not sure anyone still really believes this. At any rate, they shouldn’t.

There are several great blogs and other online communities to help one get a sense of the people working on these topics now, and to become familiar with some of the topics and issues. Warp, Weft, and Way, focusing on Chinese and Comparative Philosophy, is one of the most active and oldest blogs. 20th Century Mexican Philosophy provides discussion and links to many valuable resources. The Blog of the APA has been running a series of posts on teaching material from outside the traditional canon, such as this wonderfully helpful entry by Liam Kofi Bright and Peter Adamson, So You Want to Teach Some Africana Philosophy?

It has now been almost exactly six years since Jay Garfield and Bryan Van Norden published their “If Philosophy Won’t Diversify, Let’s Call It What It Really Is” in the New York Times, and it has been five years since Van Norden published his follow-up book, Taking Back Philosophy: A Multicultural Manifesto. They and many others have been pointing out, for years, that the vast majority of philosophy departments in the United States (and most other parts of the Anglophone world) offer courses only from one strand of the world’s philosophical traditions, the Anglo-European strand. (And even within that strand, it is narrow, giving prominence to Ancient Greece, France, Germany, the UK, and the US.)

Please, share in the comments if you teach at an institution that has made changes in this direction!

Even if you don’t create a whole new course, work on adding material from outside the standard story into your classes in Ethics, Epistemology, Metaphysics, Mind, Political Philosophy, and so on. Many of the above resources will help in that regard, too, and this is, in some ways, an even more direct way to expand the standard story and to make evident the way in which philosophy really is a subject that has been done by people of all kinds and everywhere.

So, for much of the recent history of philosophical education in the Anglo-European world, what was pointed 75 years ago is still what is in the story today. Martin Luther King Jr.’s syllabus for an introductory social and political philosophy class he taught at Morehouse College 60 years ago could be identical to one that might be taught today.

The overall suggestion here is to do what one can to support PhD and MA students in becoming experts and competent teachers with respect to philosophical work outside the standard story.

(6) Hire People Who Know More of the Story

There are many reasons to expand the story we tell about philosophy. But a main reason is just that the best, most interesting, and even the correct answers to philosophical questions that interest us might be found anywhere. If we think there are genuine answers here, we should be concerned about parochialism. And we should be concerned about the streetlight effect.

As I hope is clear, although it might have been hard to know where to begin 10 or 15 years ago when thinking about trying to learn more, it is considerably easier now. Please mention other resources in the comments!

There are two broad families of answers. The first aims at justification and vindication: here are the substantive, justifying reasons why this is what we teach and require and put at the center of ‘Philosophy’ in our educational institutions. The second aims at debunking these justifications (arguing that there is no justification for doing things this way) and supplementing that with diagnosis and historicization: here are the empirical explanations for why this what we do; notice that there are no justifying reasons in that story, nor no new justifying reasons to embrace now.

First suggestion: if you regularly teach philosophy, see it as a personal project to develop competence with material in your areas of specialization and/or competence from a philosophical tradition outside of the Anglo-European tradition that could be brought into your regular teaching (and perhaps also your advising and research).

Very few people who graduated with an undergraduate degree and a PhD in Philosophy from schools in North America, Australia, or the UK will have had any courses in any of Africana, Buddhist, Chinese, Indigenous or Native American, Indian, Islamic, Jewish, Latin American, or any other non-Anglo-European philosophical work. This is the central mechanism of the vicious cycle of ignorance that keeps us where we are. The only way to get out of the cycle is for many of us who were exposed only to the standard story to do some work. We can’t wait for someone else to do it. We aren’t teaching anybody else to do it. As Garfield and Van Norden wrote in 2016:

At Rutgers, we somewhat regularly offer courses on African, Latin American, and Native American Philosophy, Hindu Philosophy, Buddhist Philosophy, Islamic Philosophy, Jewish Philosophy, and Chinese Philosophy, but these are not listed as courses that fulfill any of the philosophy major requirements.

As those of us who went through such programs know, this story begins in Ancient Greece with fragments of Thales and Parmenides and a few others, and considerably more from Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle; skips forward to Medieval Europe and Anselm and Aquinas (or skips this period entirely); continues through a few prominent ‘early modern’ or ‘modern’ Anglo/European men (Descartes, Hobbes, Locke, Hume, Kant, maybe also some Leibniz, Spinoza, and Rousseau); picks up a few others in the 19th Century (Bentham, Hegel, Nietzsche, Marx, Mill); and arrives with an early 20th century philosophy origin story that goes through Frege, Russell, Carnap, Wittgenstein and into central figures like Quine, Kripke, Lewis, Rawls; and then a topically-driven focus on many distinct philosophers in the last quarter of the 20th Century and early 21st Century on the analytic side (substitute Husserl, Heidegger, Sartre, Derrida, Merleau-Ponty, Deleuze, Foucault, etc., on the continental side). The dominant version of the story includes no chapters on African, Chinese, Indian, Latin American, or Indigenous or Native American voices or views; nothing (or almost nothing) from the long grand traditions intertwined with Buddhism, Islam, or Judaism; nothing from other non-Anglo-Europeans.

I expect that almost all of us teach and study in departments in which we just inherited the basic structure of coverage and the (at best) implicit understanding of philosophy revealed by that structure. These are the courses on the books, these are the professors we have to teach them, this is what I learned about in my philosophy education, these are the readers and textbooks we use, this is what we know about already, so, this is philosophy.

Many of these suggestions ask for some effort and even sacrifice on the part of current professors and graduate students in philosophy. It’s worth talking about the reasons to see this both as beneficial and morally imperative. There are several reasons, and they do not compete, although they may differ in the degree and nature of force they provide.

There are almost certainly philosophers and people teaching and studying philosophy outside of your home institution’s department. They are quite likely to be teaching and studying philosophical work from outside the standard story. They might be in Departments of Religion, East Asian Studies, History, American Studies, Africana Studies, Comparative Literature, and so on. Learn about who they are. Reach out to them. Build connections between them and the Philosophy department. Co-teach with them. Co-organize conferences with them. Encourage your Philosophy students to take their classes. Cross-list their classes with Philosophy. Give them a presence on your departmental webpage. Perhaps, if it makes sense, pursue giving them more institutional power within Philosophy (through joint-appointments and so forth).

Obviously, that’s not any kind of argument toward substantive justification. We might try to come up with some attempts at post hoc rationalizations, but, once we acknowledge we don’t know anything at all about what is in the shadows, why should we continue to maintain that the pedagogical light is shining in just the right place?

Having these courses either be required for the major or at least count for a major requirement is essential for changing the story. It also is essential for creating a new generation of philosophers with more competence than the ones before it with respect to work outside of the Anglo-European tradition. In my experience, these classes are also very popular and bring in many students who might not otherwise have been considering Philosophy as a field of study.

* * * * *