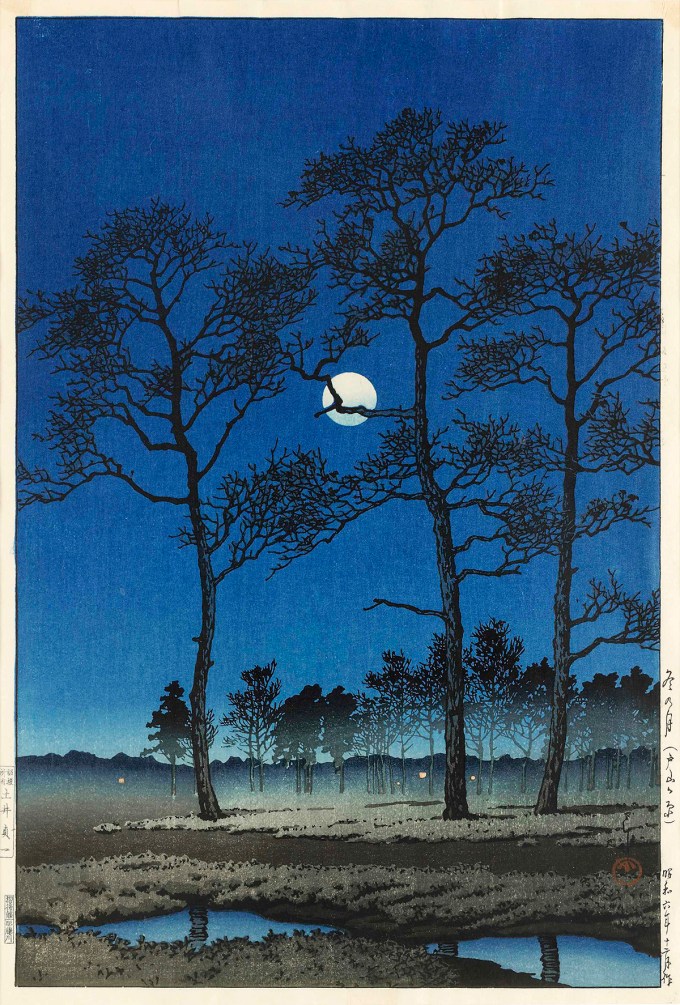

Noting that “the mortal who has never enjoyed a speaking acquaintance with some individual tree is to be pitied,” for a tree “brings serene comfort to the human heart,” Comstock celebrates winter as the season that welcomes the most intimate connection between the human heart and trees:

Ages may have passed before man gained sufficient mental stature to pay admiring tribute to the tree standing in all the glory of its full leafage, shimmering in the sunlight, making its myriad bows to the restless winds; but eons must have lapsed before the human eye grew keen enough and the human soul large enough to give sympathetic comprehension to the beauty of bare branches laced across changing skies, which is the tree-lover’s full heritage.

There is something about the skeletal splendor of winter trees — so vascular, so axonal, so pulmonary — that fills the lung of life with a special atmosphere of aliveness. Something beyond the knowledge that wintering is the root of trees’ resilience, beyond the revelation of their fractal nature and how it salves the soul with its geometry of grief. Something that humbles you to the barest, most beautiful face of the elemental.

In 1902, nine years before she laid the cultural groundwork for what we now call youth climate action in her exquisite field guide to wonder, Comstock wrote an article for the magazine Country Life that became, fourteen years later, her slender, tender book Trees at Leisure (public library | public domain) — a love letter to the science, splendor, and spiritual rewards of our barked, branched, rooted chaperones of being.

Winter, Comstock observes, is the best time for learning to tell trees apart from each other. How to discern, and inevitably fall in love with, different species — the sycamore, with its “great undulating, serpent-like branches, blotched with white”; the golden osier willow, with its “magnificent trunk and giant limbs upholding a mass of terminal shoots that tinge with warm ocher the winter landscape”; the apple, with its “maze of twigs” and its “great twisted branches making picturesque any scene” — is what Comstock explores throughout the rest of her sapling-sized, sequoia-spirited Trees at Leisure.

In winter, we are prone to regard our trees as cold, bare, and dreary; and we bid them wait until they are again clothed in verdure before we may accord to them comradeship. However, it is during this winter resting time that the tree stands revealed to the uttermost, ready to give its most intimate confidences to those who love it. It is indeed a superficial acquaintance that depends upon the garb worn for half the year; and to those who know them, the trees display even more individuality in the winter than in the summer. The summer is the tree’s period of reticence, when, behind its mysterious veil of green, it is so busy with its own life processes that it has no time for confidences, and may only now and then fling us a friendly greeting.

For a different portal into growing more intimate with trees, explore Italian artist, designer, futurist, and inventor Bruno Munari’s uncommon vintage gem Drawing a Tree. Then, for no reason other than sheer delight, savor Women in Trees.

A century before Ursula K. Le Guin so mightily unsexed the universal pronoun, Comstock considers the role trees have played in “the aesthetic education of man” since the dawn of evolutionary time and writes:

Complement it with Trees at Night — a playful, poignant meditation on our relationship to trees, painted by the cartoonist Art Young in the final years of Anna Botsford Comstock’s life — and Paul Klee, writing in the same era, on why an artist is like a tree, then revisit Ursula K. Le Guin’s love poem to trees and Rilke on winter as the season for tending to your inner garden.

I know of no one who has captured that singular enchantment better than the artist, naturalist, philosopher, entomologist, and educator Anna Botsford Comstock (September 1, 1854–August 24, 1930).