Imagine, then, my delight when a friend handed me a copy of More Women in Trees (public library) by the German photography editor, collector, and curator Jochen Raiss, a follow-up to his improbable hit Women in Trees (public library) — an entry in the ledger of lovely things created by the confluence of chance and choice (which, as Simone de Beauvoir observed with her keen existentialist eye, actually includes our very lives and what makes us who we are.)

It was always a rapture, a rebellion, a gauntlet against gravity and girlhood — skulking past the teachers, pushing through the boys, and racing across the schoolyard to climb the colossal walnut tree, whose feisty fractal vivacity mocked the bleak Brutalist architecture of my elementary school in Bulgaria.

It delighted him enough to take home and use as a bookmark.

But then, by the marvelous pattern-recognition virtuosity of the human brain, he started finding others during his flea market excursions. He started collecting them. He started carefully cataloguing them in antique wooden crates.

Complement the mischievous and marvelous Women in Trees and More Women in Trees with Dylan Thomas’s “Being But Men” — his love poem to trees and the wonder of being human, composed in the same era, an era when “man” included “woman” while erasing women — then revisit artist Art Young’s century-old meditation on human nature in tree silhouettes and Italian visual philosopher Bruno Munari’s existential lesson in how to draw a tree to see yourself.

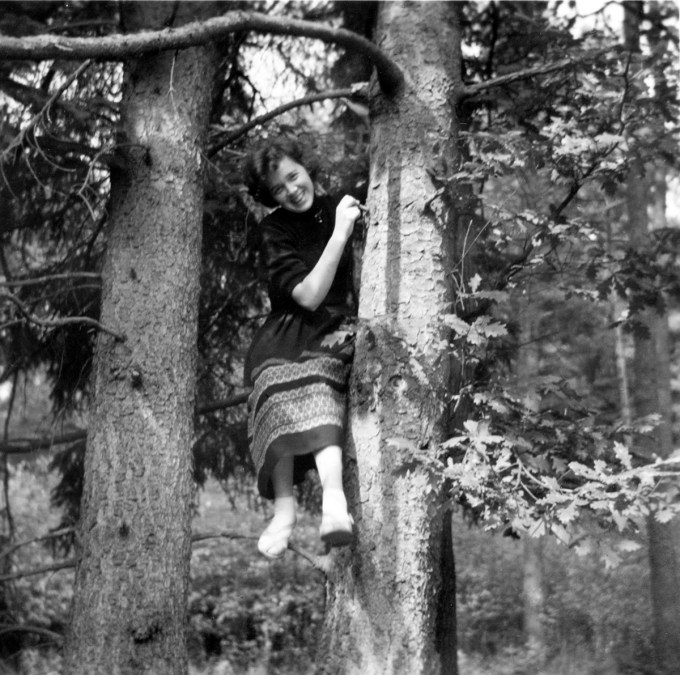

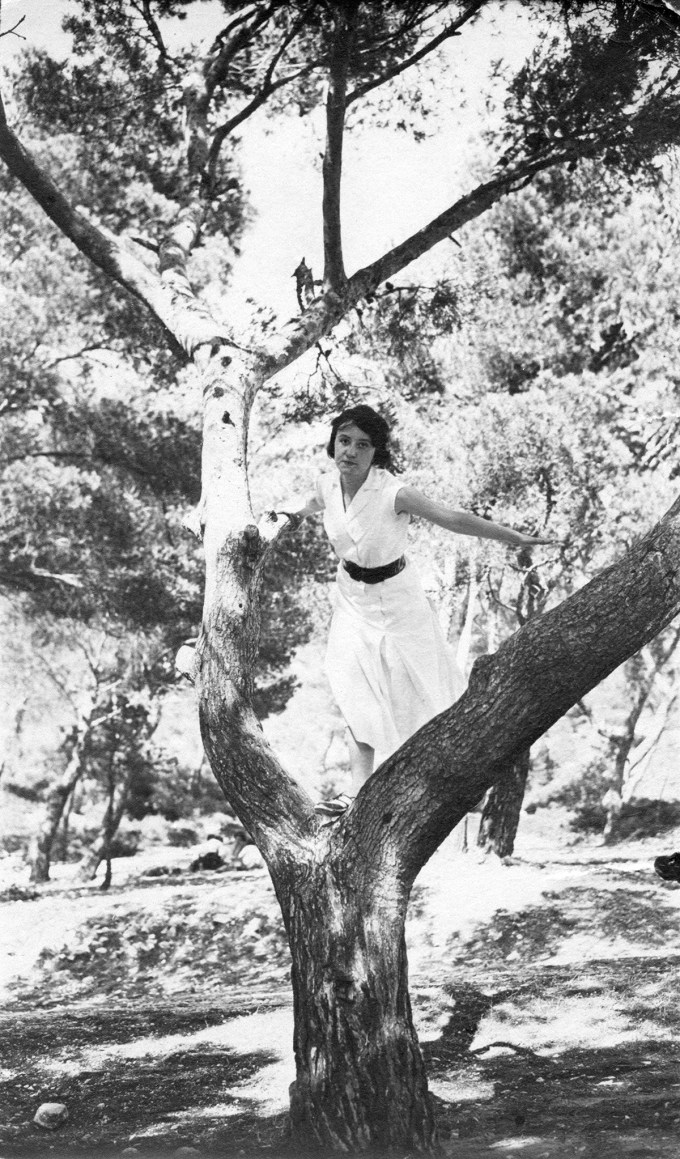

It began with a single photograph Raiss found while rummaging through the bin of hodgepodge vintage ephemera at a Frankfurt flea market — a woman, in a tree, happy and carefree.

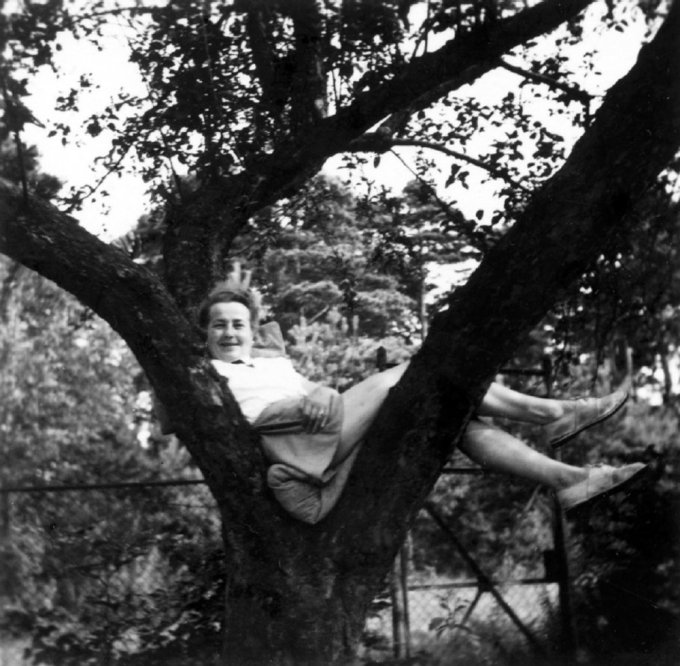

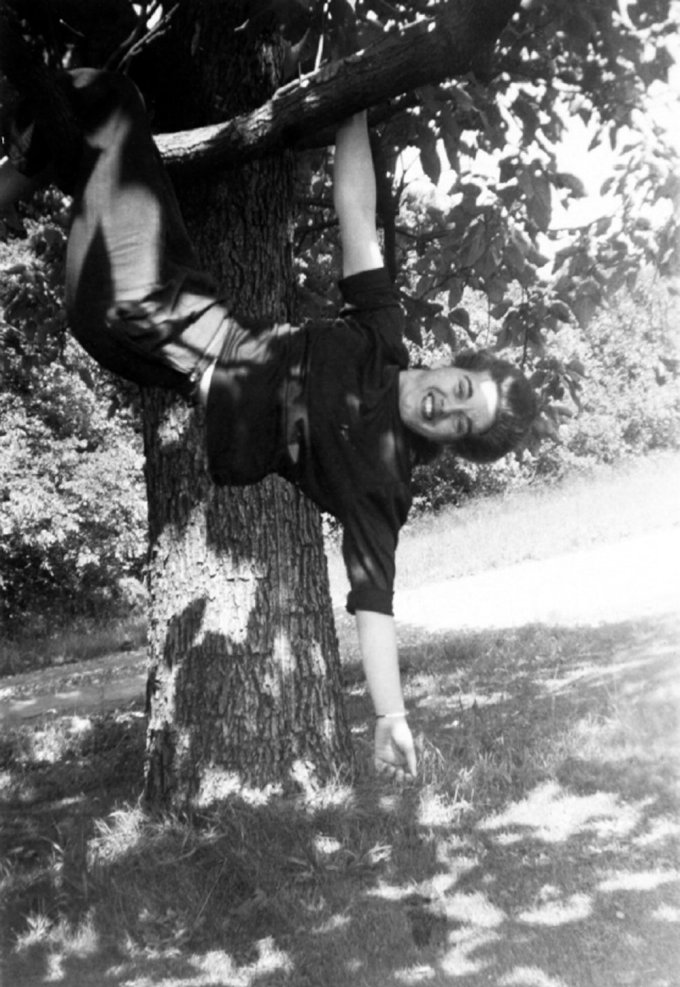

Over the course of a quarter century, he amassed some 140 specimens of the genre, the anthropology of a secret tribe — strange, sweet, subversive photographs of anonymous women engaged in acts of arboreal daring, taken before color film became a commonplace and feminism a conscience.

Their mute, defiant delight seems to be saying, “My grandmother was jailed for wearing trousers but I can win the Nobel Prize in Physics”; seem to be saying, “My mother could not vote but my daughter can be chancellor”; seem to be saying, “I can go as high as I please, damned be gravity and grace, so I can peer at broader horizons.”

Then there was my rural-grandmother’s cherry tree, into whose balding crown I would disappear to sulk when my parents discarded me to the country for yet another endless summer. And the copse of horse-chestnut across the street from my city-grandmother’s lightless apartment, whose friendly open-palmed leaves beckoned me to find the first of the spiky green fruit, before they released their shiny brown pebbles of seed onto the cracked sidewalk.

Along the way, I came to cherish trees not only as aerial playgrounds, but as wonders of immense poetic, philosophical, and ecological import.

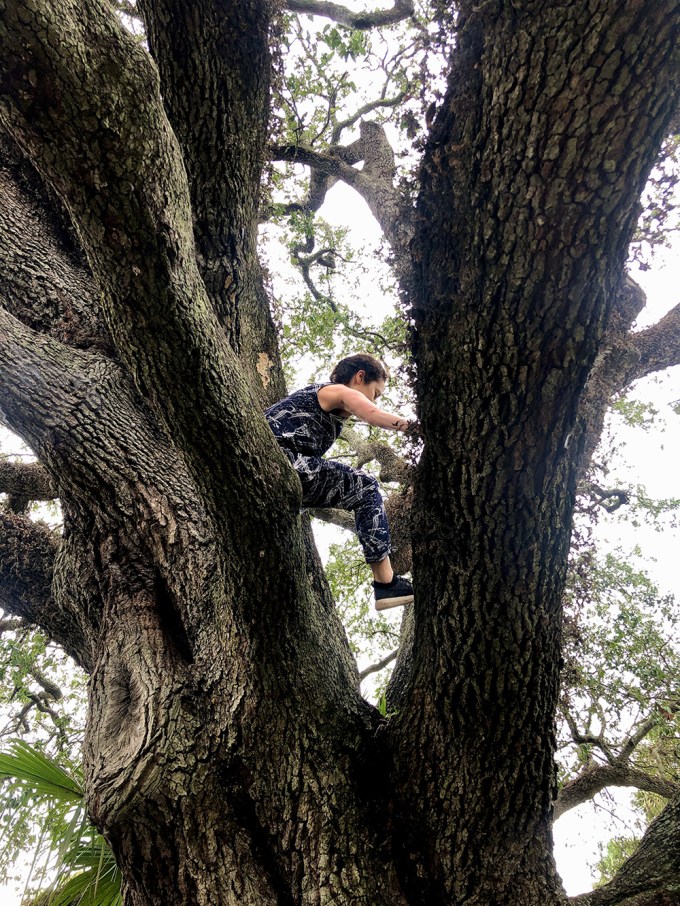

Even as my wrist-bones turned from twigs to branches and adulthood carried me across the Atlantic to lay down my sovereign roots, the impulse never left me, perhaps because the child never leaves us. I climbed — not with the skills and scientific motive force of an arbornaut but with the sylvan transcendence of Blake — oaks in Brooklyn and coastal redwood in Bolinas and Douglas Fir in Olympia and the Tree of Life in New Orleans.

Some of the photographs were taken when Germany was the roiling epicenter of World War II. Some of the women in them probably hailed Hitler. Some probably died in concentration camps. But for those moments suspended in the branches above the current of their epoch, islanded in space and time, they shared something singular and lovely, united in a sisterhood of sylvan joy.