In the 1950s, Rai Weiss fell in love with a pianist, fell in love with his lover’s passion for music, and went on to invent the colossal instrument that captured the sound of spacetime, revolutionizing our understanding of the universe and earning him the Nobel Prize in Physics.

It may be some eloquent appreciations read in a book, or some preference expressed by a gifted friend, that may have revealed unsuspected beauties in art or nature; and then, since our own perception was vicarious and obviously inferior in volume to that which our mentor possessed, we shall take his judgments for our criterion, since they were the source and exemplar of all our own. Thus the volume and intensity of some appreciations, especially when nothing of the kind has preceded, makes them authoritative over our subsequent judgments. On those warm moments hang all our cold systematic opinions; and while the latter fill our days and shape our careers it is only the former that are crucial and alive.

Taste is formed in those moments when aesthetic emotion is massive and distinct; preferences then grown conscious, judgments then put into words, will verbal reverberate through calmer hours; they will constitute prejudices, habits of apperception, secret standards for all other beauties. A period of life in which such intuitions have been frequent may amass tastes and ideals sufficient for the rest of our days. Youth in these matters governs maturity, and while men may develop their early impressions more systematically and find confirmations of them in various quarters, they will seldom look at the world afresh or use new categories in deciphering it. Half our standards come from our first masters, and the other half from our first loves. Never being so deeply stirred again, we remain persuaded that no objects save those we then discovered can have a true sublimity.

In the 1850s, Emily Dickinson’s passionate first love shaped her uncommon body of work for a lifetime to come, shaped the spare and searing poems that would go on animating lives for generations to come.

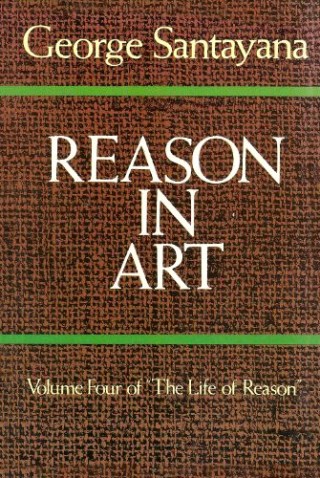

More than a century later, The Life of Reason remains an intellectual lavishment. Complement this particular fragment with Joseph Brodsky on how to develop your taste in reading, W. I. B. Beveridge on the cultivation of scientific taste, and Wordsworth on the artist’s responsibility of elevating taste.

Considering the formative infrastructure of our frames of reference and our standards, our likes and dislikes, our aesthetic and moral judgments — that colossal compass of sensibility we call “taste,” by which we orient ourselves to the world, for we only ever orient by our yeas and nays — Santayana writes:

With uncommon insight into these joint fomentations of heart and mind, the great Spanish-American philosopher, poet, essayist, and novelist George Santayana (December 16, 1863–September 26, 1952) takes up the question of how our sensibilities are formed in a portion of Reason in Art — the fourth volume, nestled between Reason in Religion and Reason in Science, of his five-volume 1906 masterwork The Life of Reason; or, the Phases of Human Progress (public domain | public library).

In 1957, after becoming the second-youngest laureate of the Nobel Prize in Literature, Albert Camus hastened to send his childhood teacher a tender letter of gratitude for shaping the spirit and sensibility of the boy that made the man that made the work that won humanity’s highest accolade.

In consonance with the trailblazing astronomer Maria Mitchell’s observation that “whatever our degree of friends may be, we come more under their influence than we are aware,” and with an eye to our criteria for beauty — which apply to beauty in the broad Robinson Jeffers sense of not only aesthetic beauty but intellectual and moral beauty — Santayana adds: