The other Jon survived, and lived to remember the poetry on the forest floor as a serene moment amid the terrifying uncertainty and the adrenalized pain. Reflecting on the experience, now both of them twice the age they were then, this Jon writes:

Complement with Gwendolyn Brooks’s lifeline of a poem and Mary Oliver on how books saved her life, then revisit the strikingly kindred story of how Oliver Sacks saved his own life by reciting poetry.

“A life of patient suffering… is a better poem in itself than we can any of us write,” the young poet Anne Reeve Aldrich wrote to Emily Dickinson shortly before her untimely death. “It is only through the gates of suffering, either mental or physical, that we can pass into that tender sympathy with the griefs of all of mankind which it ought to be the ideal of every soul to attain.”

Why are we not better than we are?

But this transcendent idyll was soon interrupted by the brute impartiality of nature — a boom, then a crash, then faster than the speed of reason, a colossal tree atop one of the three friends. (Incidentally, also named Jon.)

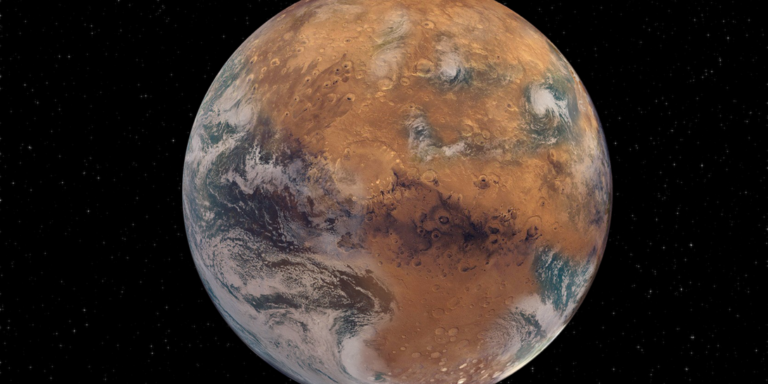

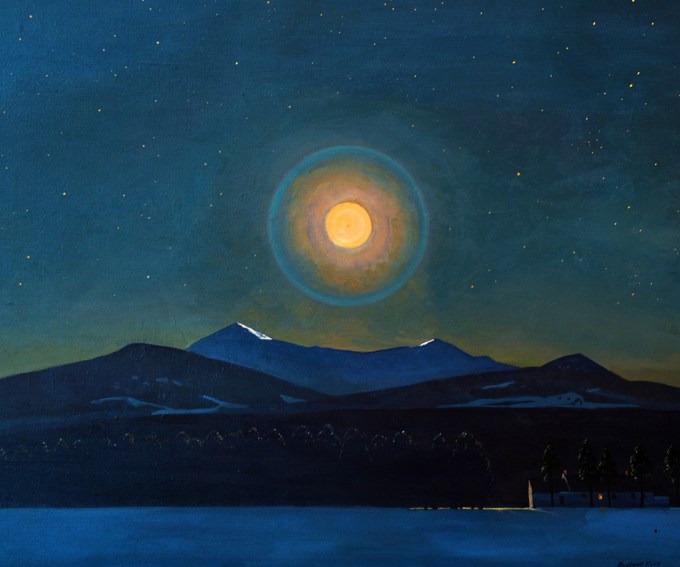

As the boat that delivered us vanished, the drone of its engine dampening into a murmur and then finally trailing off, it became unthinkably quiet on the beach, and the largeness and strangeness of our surroundings were suddenly apparent… It felt like those scenes of astronauts who, having finally rattled free of the earth’s atmosphere, slip into the stillness of space. Except we weren’t in space. We were on earth — finally, really on earth.

Jon and I would spend about an hour and a half together alone on the forest floor. I ran through everything in my quiver—Kay Ryan, A. R. Ammons, Michael Donaghy—padding each poem with little prefatory remarks, while Jon said nothing, just signaled with his eyes or produced a sound whenever I checked in. I felt like a radio DJ playing records in the middle of the night, unsure if anyone was listening. And here’s one about owls by Richard Wilbur, I would tell Jon, and off we would go.

Suffering is the name we give to how we live with life’s imperfection, and with our own — which is so often the wellspring of our profoundest suffering. How we bear this imperfection, what we make of it, is our great living poem.

They managed to radio for help. After firing a flaccid flare, they began fearing they were undiscoverable in the uncharted wilderness far inland from their camp. All they knew was that they had to keep him conscious until help arrived, pinned as he was by the tree in an icy creek, hypothermia on top of all the internal bleeding that was no doubt flooding his system.

This would become the animating question of Jon’s life, as a writer and as a human being; a question that each of the essays whispers or bellows, none more poignantly than one titled by a kindred question: “Why These Instead of Others?” — his account, across the abyss of twenty years, of a trip to the remote reaches of Alaska he took with two of his college friends in the spring of life.

This was poetry as time-dilation and poetry as prayer — a way to keep a drifting mind anchored in the questions that daily keep us from sleeping and quicken the creative restlessness we call art, we call meaning. One way to answer that long-ago question: with this tenderest testament to how, sometimes — and mostly when life boughs us to our knees on the forest floor of crisis — we are better, better than we ever thought we could be while coasting in the illusory safety of our daily lives.

Twenty years years ago, I was working at a small literary magazine in New York City, screening the bulging slush pile of poetry submissions for anything that the editors might be interested in publishing. Please know that passing judgment on all these people’s poems made me queasy. I was twenty-two years old, not especially well-read, and my only previous full-time employment had been as a kosher butcher. I could only like what I liked. Also, I was extraordinarily sad. My father had died a year earlier, and the grief and bewilderment I’d kept tamped down were beginning to burble upward. I felt alone. I felt lost. And I was fixated on figuring out why everything was so hard, what I was doing wrong. Some evenings, I’d walk the fifty-eight blocks home from the office, excessively serious-faced, wrenching my mind around like a Rubik’s Cube, struggling to make it show a brighter color.

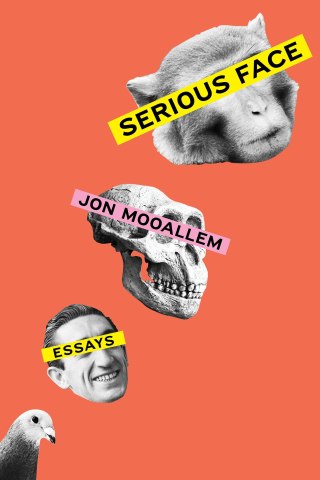

This awareness pulsates throughout the essay collection Serious Face (public library) by Jon Mooallem — one of the finest magazine journalists of our time, and one of the most original storytellers. He writes in the preface:

By some animal instinct, kneeling over the other Jon, this one leaned on the semi-automation of his mind:

What can a person say? I had two literature professors in college who made us memorize poems. You never knew when some lines of verse would come in handy, they claimed. One liked to brag that, while traveling through Ireland, he found that if he spat out some Yeats at a pub, he could drink for free. This is how I wound up reciting a love poem to Jon.

That poem was “The Shampoo” by Elizabeth Bishop. He moved on to Auden’s “The More Loving One.” Then some Robert Frost, some Kay Ryan. He recounts:

He was unsure — how can anyone be sure? — that he was doing the best thing, that he couldn’t do something better, be better. But it was the best he had.

An epoch after Rockwell Kent voyaged there to find the crux of creativity, the three young men arrived into a realm of remoteness so discomposing to their city consciousnesses as to appear entirely alien:

Moved by the improbable way in which a stranger’s poem had helped Jon save his friend’s life and had shaped his own, I asked him to read it for us half a lifetime after his chance encounter with it in the submissions pile of his entry-level job, with a side of Bach:

Even my reciting those poems, which to me had always felt like a moment of utter helplessness, became, in Jon’s telling, a perfect emblem of that streak of serendipitous problem-solving. “You conveyed a calmness,” he told me recently. And then, from among the thousands of poems whose literary merit he was uncomfortably tasked with brokering, one stopped him up short: “Frost in the Fields” by Eric Trethewey, no longer alive; one particular line in it crowning the lyric of landscape: