Knowing your feelings is hard too because there’s so much emotion, it’s hard to tell which is truest. Part of you might want to leave right away; part of you might want to stay forever. That’s why I advised that you satay “for as long as you can.” What that means will vary with each person, with the needs of the parent and the other relations. A day might be enough, or it might take a whole month. If it’s a prolonged situation, it might be good to leave for a few days and come back. Those decisions are so personal they are beyond the scope of my advice — except my advice to pay close attention to yourself. If you feel, To hell with this, I’m getting out, don’t worry — there’s room for that. Maybe in fact you should leave. But before you do, be sure that voice is not shouting down a truer one. When your parents die, you will never see them again. You might think you understand that, but until it happens, you don’t.

Like a Zen koan, this fact becomes utterly discomposing when you begin thinking deeply about the fundamental, layered realities beneath the mundane, even banal factuality of the fact. Parents — the very notion of them. The notion that you — this immensely complex totality of sinew and selfhood, this portable universe shimmering with a million ideas and passions and little ways of being-in-the-world that make you you — began as a glimmer in someone else’s eye, a set of chemical reactions that became molecules that became cells in someone else’s body before they constellated into you. The notion that so many dimensions of your personhood, so many of the givens you take for granted in making sense of the world, were forged by someone other than yourself (and possibly other than the body that begot the cells that became you) — someone who occupies, in the cosmogony of you, this strange and staggering position of arbiter between the existence and nonexistence of the particular you that you are.

Nothing makes this plainer than being in the presence of a dying person for any length of time. Death makes human beings seem like very small containers that are packed so densely we can only be aware of a fraction of what’s inside us from moment to moment. Being in the presence of death can break you open, disgorging feelings that are deeper and more powerful than anything you thought you knew. If you have had a loving, clear relationship with your parent, this experience probably won’t be quite as wrenching. There may in fact be moments of pure tenderness, even exaltation. But you might still have to watch your parent appear to break, mentally and physically, disintegrating into something you can no longer recognize. In some ways this is terrible — many people find it absolutely so. There is another side to it, though: In witnessing this seeming breakage, we are glimpsing the part of our parents that doesn’t translate in human terms, that which we know nothing about, and which the human container is too small to give shape to.

They say that you come into the world alone and that you leave alone too. But you aren’t born alone; your mother is with you, maybe your father too. Their presence may have been loving, it may have been demented, it may have been both. But they were with you. When they are dying, remember that. And go be with them.

My advice here is very specific and practicable. It is advice I wish someone had given me as forcefully as I’m about to give it now: When your parents are dying, you should go be with them. You should spend as much time as you can. This may seem obvious; you would be surprised how difficult it can be. It is less difficult if you have a good relationship with the parent or, even if you don’t, if you’re old enough to have lost friends and to have seriously considered your own death. Even so, it may be more difficult than you think.

“Your children are not your children. They are the sons and daughters of Life’s longing for itself,” Kahlil Gibran wrote in his poignant verse on parenting. And yet we are, each of us, someone’s child — physiologically or psychologically or both — and they sing themselves through us as we sing ourselves into our longing for life, whether we like the melody or not.

With the sensitive caveat that there exist people “to whom this general directive does not apply” and her advice is not meant as a rebuke to those people, Gaitskill addresses those of us raised by fallible parents who, in one way or another, failed dreadfully at the deepest task of parenting — unconditional love:

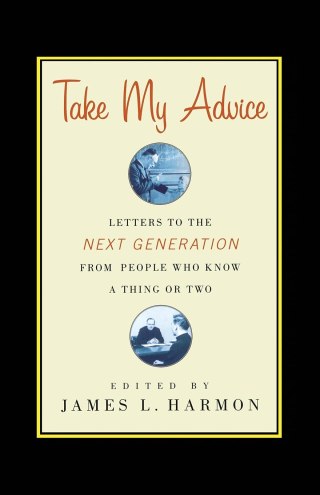

The doubly discomposing experience of what happens when that arbiter crosses the threshold of their own nonexistence is what Mary Gaitskill addresses in her thoughtful, tender contribution to Take My Advice: Letters to the Next Generation from People Who Know a Thing or Two (public library) — the wondrous 2002 anthology by artist and writer James L. Harmon, inspired by one of his own spiritual parents: Rilke and his timeless Letters to a Young Poet.

If you’re a young person who has had a bad relationship with your parent, it’s a nightmare of anger, confusion, and guilt. Even if you hate them, you may still not want to believe it’s happening… Even if your parents have been abusive, physically or emotionally, they are part of you in a way that goes beyond personality or even character. Maybe “beyond” isn’t the right word. They are part of you in a way that runs beneath the daily self. They have passed an essence to you. This essence may not be recognizable; your parents may have made its raw matter into something so different than what you have made of it that it seems you are nothing alike. That they have given you this essence may be no virtue of theirs — they may not even have chosen to do so. (It may not be biological either; all I say here I would say about adoptive as well as birth parents.)

Because any emotional experience we have when facing another is always an emotional experience we have within, and about, ourselves — especially if that other gave rise to this self — facing this supraknowable quality is facing the limits of our own self-knowledge. Gaitskill writes:

Complement this fragment of Take My Advice — which also includes novelist Richard Powers on the most important attitude you can take toward your life and philosopher Martha Nussbaum on how to honor your inner world — with Richard Dawkins on the luckiness of death, Marcus Aurelius on embracing mortality as the key to living fully, and Zen Hospice Project founder Frank Ostaseski on the five life-redeeming invitation to extend in facing death, then revisit this tender illustrated meditation on the cycle of life.

In a sentiment on the surface contradictory but in fact consonant with the deeper meaning of what artist Louise Bourgeois inscribed into her lifelong diary in her old age — “You are born alone. You die alone. The value of the space in between is trust and love.” — Gaitskill concludes:

Gaitskill writes:

Being with a dying parent, Gaitskill notes, is a way of honoring the fact — so basic yet so incomprehensible a fact — that they will soon be gone, and with them will go your experience of being their child in the way you have known, a fundamental way in which you have known yourself. At the heart of this dual recognition is “the hard truth that we know nothing about who we are or what our lives mean.” She writes: