Mark Alfano, associate professor of philosophy at Macquarie University, who studies Nietzsche, shares a technique, called “distant reading,” in response to a question from interviewer Richard Marshall at 3:16AM:

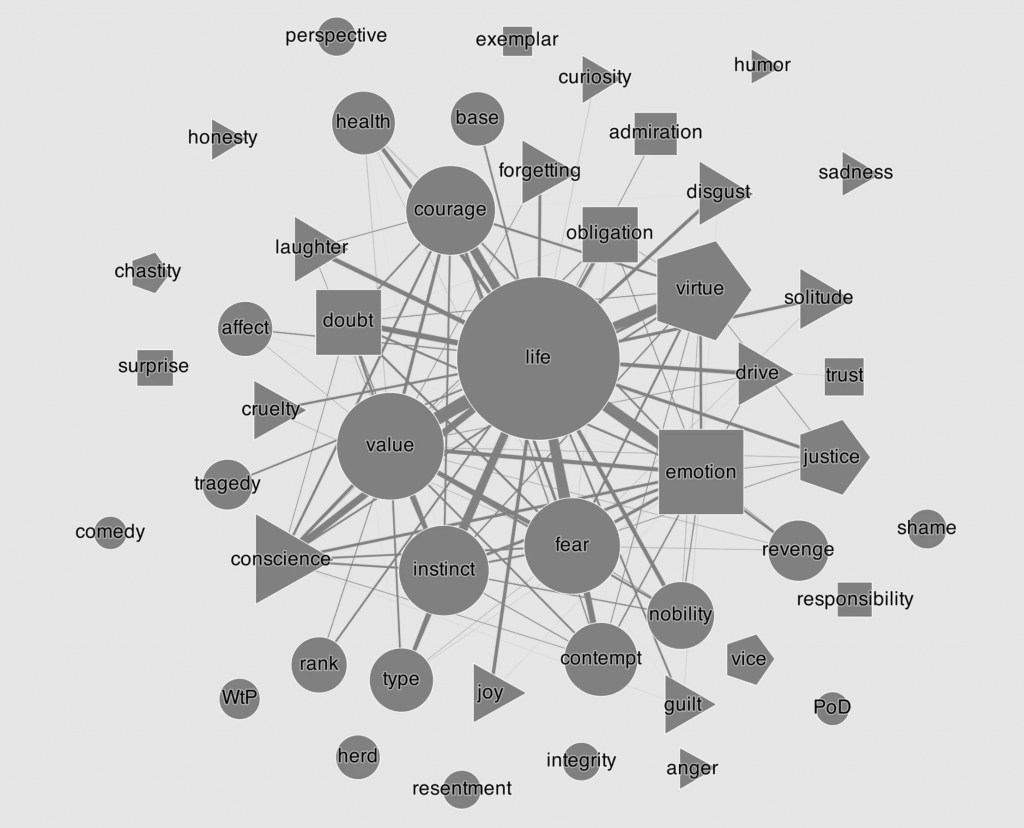

The next step is really the one you asked about: how to use distant reading to complement close reading? There are two main uses. First, this kind of analysis makes it possible to answer questions of the form, “What does Nietzsche talk about when he talks about X?” So for instance, what else does he talk about when he talks about virtue, or about courage, or about contempt, or about conscience? In the book, I visualize these interrelationships with (what I think are) pretty pictures using Gephi.

“I don’t think the computers will ever replace the people when it comes to interpreting philosophical texts. It’s rather that we humans can use computers to help keep ourselves honest and unearth patterns that would be difficult to detect if we did everything manually.”

I want to be clear that I don’t think the computers will ever replace the people when it comes to interpreting philosophical texts. It’s rather that we humans can use computers to help keep ourselves honest and unearth patterns that would be difficult to detect if we did everything manually. But we are the ones to offer the interpretations, and our interpretations will always need close, careful, and contextualized reading. That (along with the pretty pictures) is what I think distant reading is or at least should be about.

But the actual analysis is entirely structural and mathematical. Answering that question on its own doesn’t tell you how Nietzsche relates various concepts, but it strongly suggests that he does relate them. This leads to the second thing, which is guided close-reading. The idea is that if Nietzsche keeps talking about X and Y in the same passage, he probably thinks they’re related in some way. So then I go through all of those passages with an eye specifically to the relationship between those concepts. This was a new way of reading for me. Previously, I’d either read cover-to-cover or would have a hunch and search for one or two relevant passages. Forcing myself to engage with all and only the passages in which concepts of interest crop up led me to formulate some new ideas, especially when it came to Nietzsche’s thoughts about perspectivism, about having a sense of humor, and especially about what he calls ‘solitude’.

How can those studying and intepreting figures in the history of philosophy avoid approaches that “warp or distort the philosopher being interpreted”?

The basic idea is extremely flat-footed and simple-minded: I come up with a list of concepts or constructs that, based on my reading of Nietzsche over the years as well as my familiarity with the secondary literature, are probably important for him. Then I associate each concept or construct with the German words (actually word stems) that he uses to refer to or express it. For instance, the concept of virtue is associated with anything beginning with ‘tugend’. Some concepts are associated with only one word stem, others with multiple. This is made a bit difficult because Nietzsche updated his spelling in the mid-1880s. For instance, in his earlier work, he uses ‘instinct’ and ‘affect’, but later he uses ‘instinkt’ and ‘affekt’. In order to get all and only the word stems you want, you need to be aware of the text at a detailed level. Once I’m satisfied with the list of word stem(s) associated with a given concept, I then run an algorithm over the entire corpus to find out which passages contain which concepts. I initially did this all by hand via www.nietzschesource.org , which is an outstanding resource. It took months. But then I met a computer scientist by the name of Marc Cheong who figured out how to do it automatically in the course of about a minute. We eventually published a tool that anyone with minimal coding skills can use to replicate and extend what I did in the book.

Related: A Semantic-Network Approach to the History of Philosophy

You can read the whole interview here.