Every shower that falls, every change of temperature that occurs, and every wind that blows, leaves on the vegetable world the traces of its passage; slight, indeed, and imperceptible, perhaps, to us, but not the less permanently recorded in the depths of those woody fabrics.

It is also no wonder, then, that we see ourselves so readily in trees — not only in the easy (and therefore limited) anthropomorphic sense of Western fairy tales and Eastern folk myths that have accompanied our civilization, but in the deeper, more poetic sense that reveals us to ourselves as imaginative creatures animated by a restless yearning to reconcile the ephemeral and the eternal. This is the sense William Blake captured in his most beautiful letter:

Charles Babbage, while dreaming up the world’s first computer with Ada Lovelace, marveled at how tree rings encode information about the past — living logs as precise as digital data, as primal as the human heartbeat:

The tree which moves some to tears of joy is in the eyes of others only a green thing which stands in the way. As a man is, so he sees.

Naturally, it was Rebecca I invited to read “Trees at Night” at the 2022 Universe in Verse. (A free “retrostream” of the full show is available worldwide between 12PM EST on May 21 and 4PM EST on May 22). Being one of the most devoted climate thinkers and activists of our time, she prefaced her reading with a soaring meditation on trees as an antidote to the erasures of human history and a moral compass for our planetary future — the kind of extemporaneous prose poem that can sprout from the lushest minds, next to which Johnson’s lyric loveliness rises even more majestic:

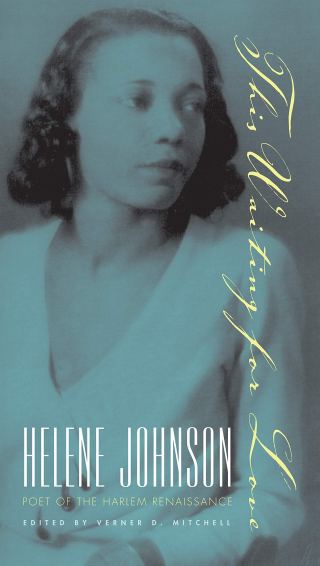

Although she published poetry for less than a decade — a common talent-corseting reality of marriage for women a mere century ago, radiating from the title of Johnson’s last published poem, at age twenty-nine: “Let Me Sing My Song” — she lived a long life, dying on her eighty-eighth birthday, having witnessed the triumph of the suffrage movement and the civilizational defeat of two World Wars, the horror of the Holocaust and the hard-won hope of Civil Rights, the discovery of the double helix and the retroviral genocide of AIDS, the dehumanizing agony of the atomic bomb and the first human footfall on the Moon. Hers was a true saeculum — that beautiful Etruscan word I learned from Rebecca Solnit, denoting the period of time since the birth of the oldest living elder in the community.

Complement with Ursula K. Le Guin’s love-poem to trees as a lens on life and death, then step into Rebecca’s inspiriting new project, Not Too Late — a welcoming portal into the climate movement for newcomers and an arsenal of reinvigoration “for people who are already engaged but weary.”

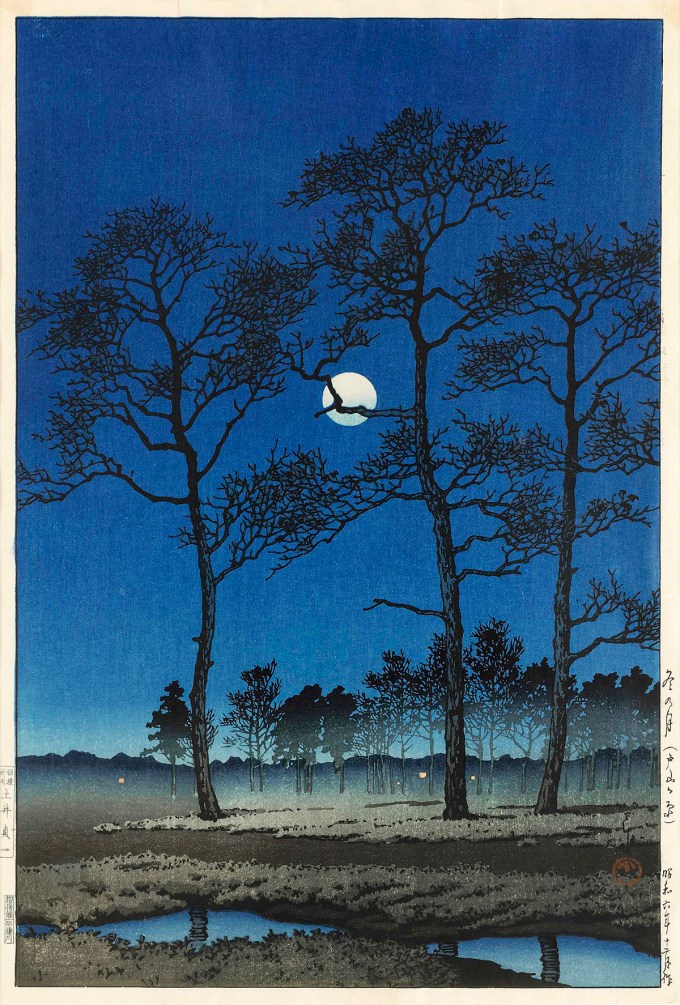

Slim Sentinels

Stretching lacy arms

About a slumbrous moon;

Black quivering

Silhouettes,

Tremulous,

Stencilled on the petal

Of a bluebell;

Ink sputtered

On a robin’s breast;

The jagged rent

Of mountains

Reflected in a

Stilly sleeping lake;

Fragile pinnacles

Of fairy castles;

Torn webs of shadows;

And

Printed ’gainst the sky —

The trembling beauty

Of an urgent pine.

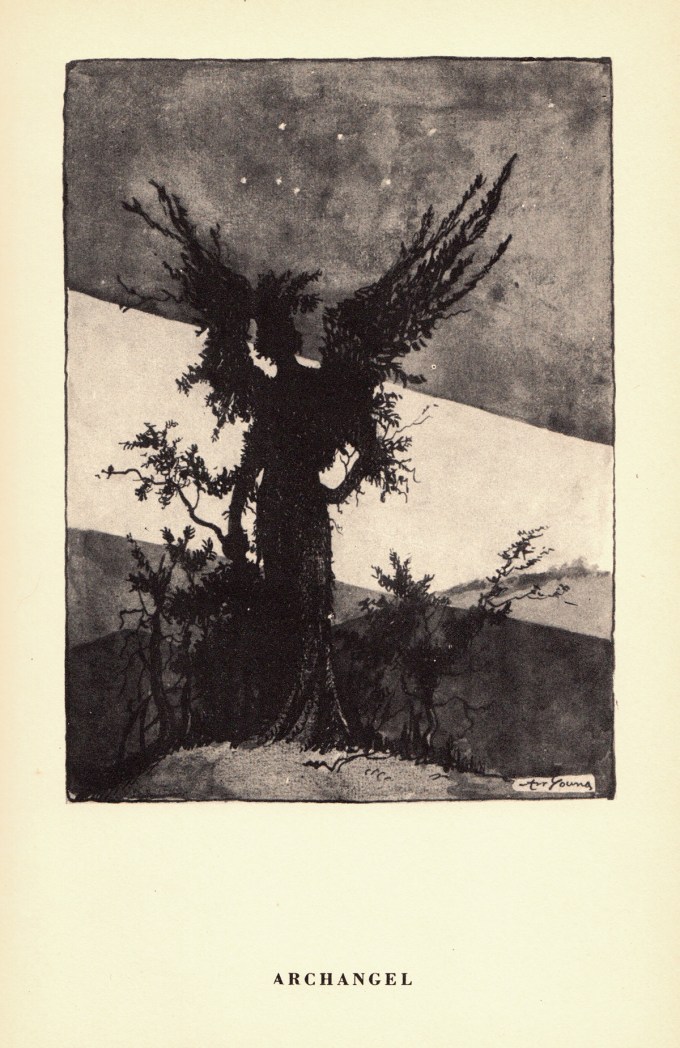

This is also the sense the young Harlem Renaissance poet Helene Johnson (July 7, 1906–July 7, 1995) captured a century and a half after Blake, in a spare and stunning poem written when she was only eighteen: “Trees at Night,” first published in 1925 — just as the high school dropout turned artist and activist Art Young’s beloved graphic series by the same title began appearing in the Saturday Evening Post, Collier’s, and LIFE, most likely inspiring the young Johnson, whose precocious erudition and literary taste must have feasted on the era’s most popular magazines.

It’s a hard thing, achieving perspective — hard for the human animal, pinned as we each are to the dust-mote of spacetime we’ve been allotted, not one of us having chosen where or when to be born, not one of us — not even the most fortunate — destined to live for more than a blink of evolutionary time. It is no wonder, then, that our lens so easily contracts to a pinhole through which the fleeting frights and urgencies of the present stream in to fill the chamber of our complex consciousness with blinding totality.

Johnson’s poem originally appeared in the May edition of the National Urban League’s Opportunity: A Journal of Negro Life, when a year later, not yet twenty, she won First Honorable Mention in the journal’s literary contest, judged by James Weldon Johnson and Robert Frost. “Trees at Night,” along with all of her surviving poems and a wealth of letters, was later included in the wonderful posthumous volume This Waiting for Love: Helene Johnson, Poet of the Harlem Renaissance (public library) by African American literature professor Verner D. Mitchell.

TREES AT NIGHT

by Helene Johnson

Remembering that we only have approximately four thousand hours helps. Taking the telescopic perspective helps. Trees, especially, help — for they remedy our loss of perspective as Earth’s own telescopes of time and mortality, each of them a perpetual death and yet potentially immortal, each a clockwork portal to the past, each “a little bit of the future,” as Wangari Maathai exulted in her Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech a blink before she became compost for future forests.