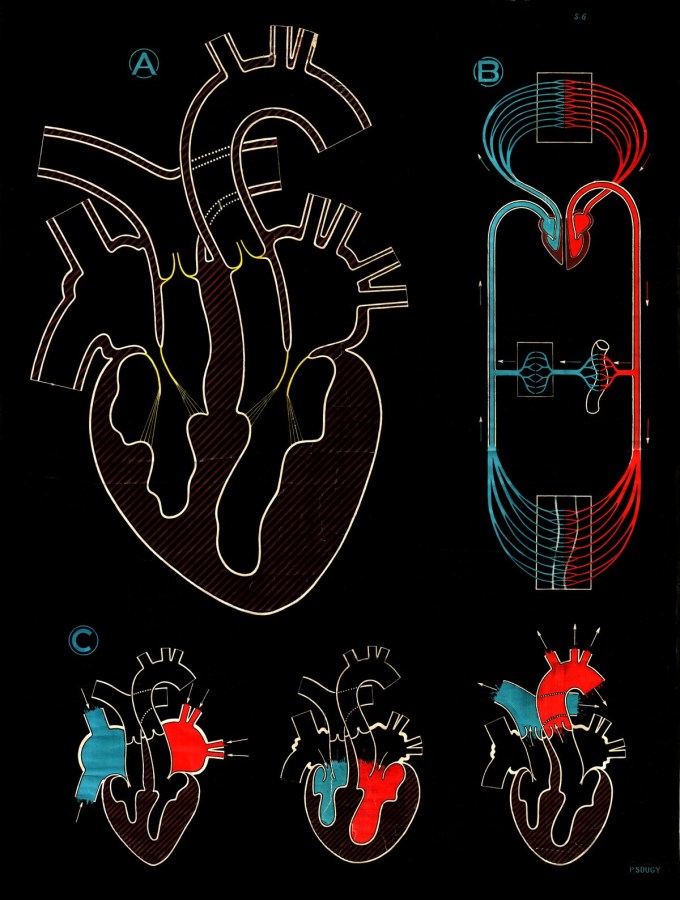

Thinking lately about what it means to have the right heart, which intimates the question of what it means to tend to one’s own heart rightly, I was reminded of a passage from what may be the loveliest, truest, most quietly transcendent thing ever written about the art of growing older: “The main thing is this,” Grace Paley wrote in 1989, “when you get up in the morning you must take your heart in your two hands. You must do this every morning.”

Love your hands! Love them. Raise them up and kiss them. Touch others with them, pat them together, stroke them on your face… Love your mouth… This is flesh… Flesh that needs to be loved. Feet that need to rest and to dance; backs that need support; shoulders that need arms, strong arms… Love your neck; put a hand on it, grace it, stroke it and hold it up. And all your inside parts that they’d just as soon slop for hogs, you got to love them. The dark, dark liver — love it, love it, and the beat and beating heart, love that too. More than eyes or feet. More than lungs that have yet to draw free air. More than your life-holding womb and your life-giving private parts… love your heart. For this is the prize.

From within the story’s broader meditation on the deepest meaning of freedom and the body as the locus of liberation, Morrison unspools this splendid sentiment from the lips of her protagonist:

A century after Walt Whitman declaimed in Leaves of Grass that “the body includes and is the meaning, the main concern and includes and is the soul,” composing his reverent catalogue of body-parts — “head, neck, hair, ears, drop and tympan of the ears… mouth, tongue, lips, teeth… strong shoulders… bowels sweet and clean… brain in its folds inside the skull-frame… heart-valves…” — Morrison writes:

Beloved remains the rare sort of masterpiece that gives the English language back to itself and your conscience back to itself. Complement this particular fragment with , then revisit Morrison on literature as rebellion and redemption, wisdom in the age of information, the artist’s task in trying times, and the little-known, lovely children’s book about kindness she wrote with her son.

In this here place, we flesh; flesh that weeps, laughs; flesh that dances on bare feet in grass. Love it. Love it hard.

I was reminded, too, of a kindred passage penned two years earlier by another titan of thought and feeling in language: Toni Morrison (February 18, 1931–August 5, 2019), writing in her 1987 masterpiece Beloved (public library) — the novel that soon made her the first black woman to receive the Nobel Prize, which she received with a speech of staggering insight into the human heart.