Seaweed. With our tendency to frame the unknown by the known and to discount the unfamiliar, we lumped a panoply of wilderness into a single category: useless plants of the sea. Today, we feed our children with crispy salted nori (Pyropia yezonesis) and find sugar kelp (Saccharina latissima) among the ingredients of every other trendy face cream and salad; we know that kelp forests house some of this planet’s most precious biodiversity and suspect that the genes of billion-year-old algae might hold the key to the origin of the plants we grow to we slake our souls on gardening and the flowers in which we seek the meaning of life.

Durant did something very different both in substance and in form.

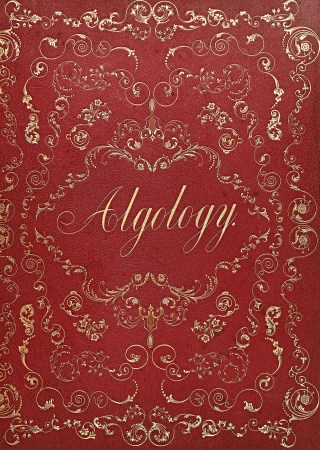

Durant spent two years living this “sort of amphibious life.” By the end, he had walked or paddled more than a thousand miles and spent “two thousand hours most agreeably devoted to the subject.” When he published his Algology: Algae and Corallines of the Bay and Harbor of New York in 1850, it was recognized for what it was — “a monument of persevering devotion” — and heralded as the epoch-making “open door to a new field of science.”

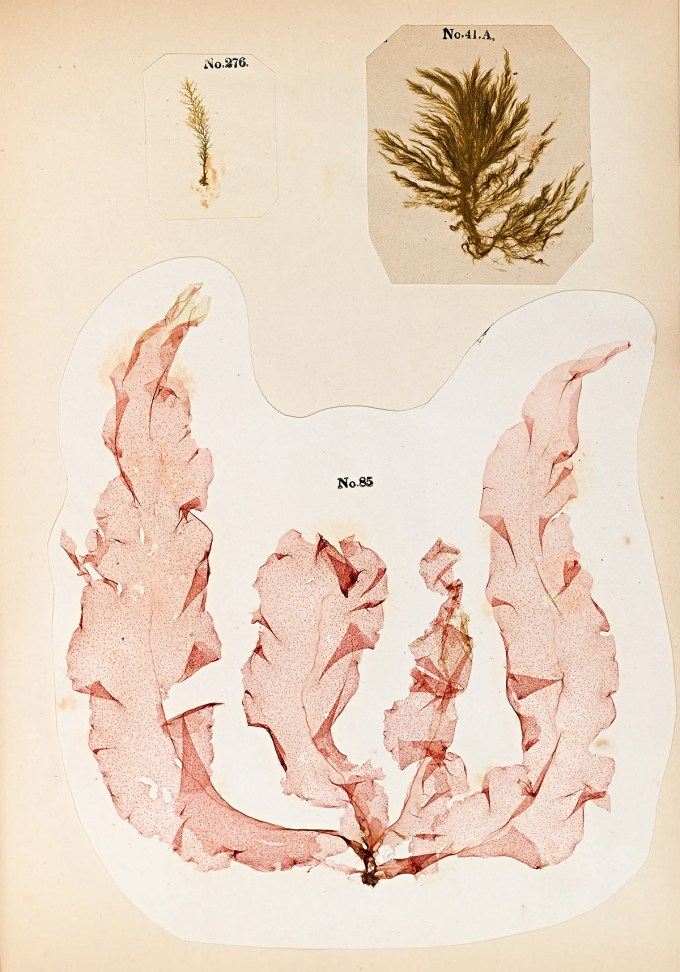

He set out to collect at least one specimen from every single algae species indigenous to New York Bay.

Charles Ferson Durant (September 19, 1805–March 2, 1873) had an improbable path to what we now call marine biology, then a curiosity-slaking hobby below the scowl of science. Having fallen in love with ballooning as a teenager, Durant had become America’s first aeronaut. By the time he was thirty, he had launched into the atmosphere more than a dozen times. On one of his aerial excursions, something went awry and he crashed into the Atlantic, where he was rescued by a passing brig.

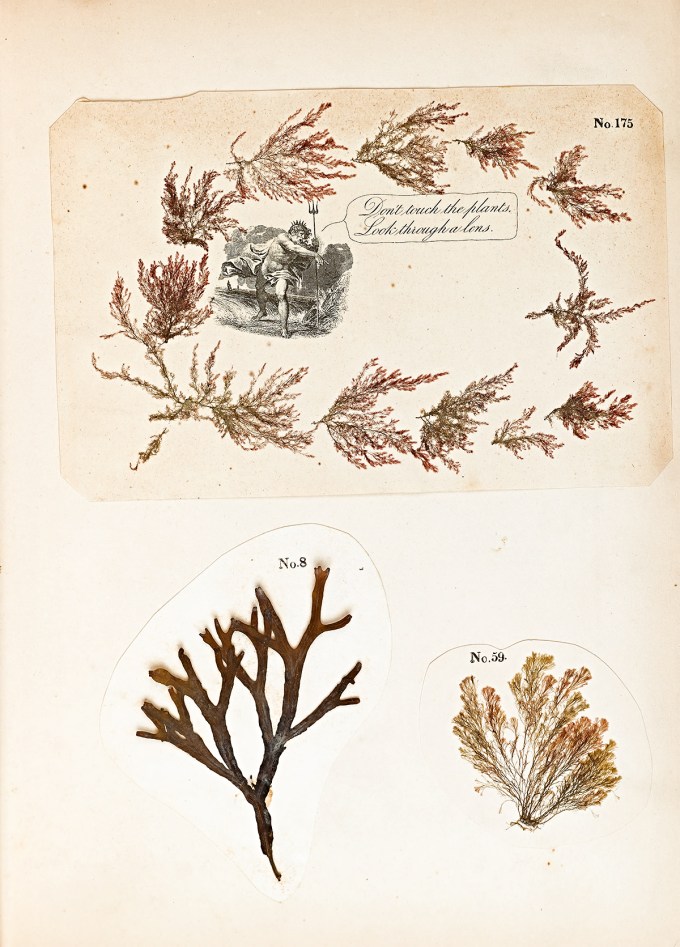

In the evening, he returned to his specimens, examining them under the microscope by candlelight and classifying them by their Linnaean taxonomy.

Seaweed albums were nothing new in Victorian times, but they were mostly made for aesthetic pleasure, rarely featured scientific classification, and existed as individual artifacts to be enjoyed by the collector and their private circle.

If my feeble efforts shall inspire a love of the science, and induce others to join in perfecting the catalogue of Algae and Corallines that flourish and decay in our waters, then I shall have accomplished a very desirable object.

Even though life in all its wonder emerged from the ocean, dragging the driftwood of our own evolutionary branch along with it, we have always been bounded by our terrestrial frames of reference. For the vast majority of our species history, the ocean remained more mysterious to us than the Moon. “Who has known the ocean?” asked Rachel Carson in the 1937 masterpiece that brought the science and splendor of the submarine wonderland to the human imagination for the first time. “Neither you nor I, with our earth-bound senses, know the foam and surge of the tide that beats over the crab hiding under the seaweed of his tide-pool home.”

And yet algae remain both magnetic and repulsive in their strangeness — emissaries of what was once our womb but is now an alien world we can fathom only incompletely, peering at its otherness through the glass wall of our earthen consciousness.

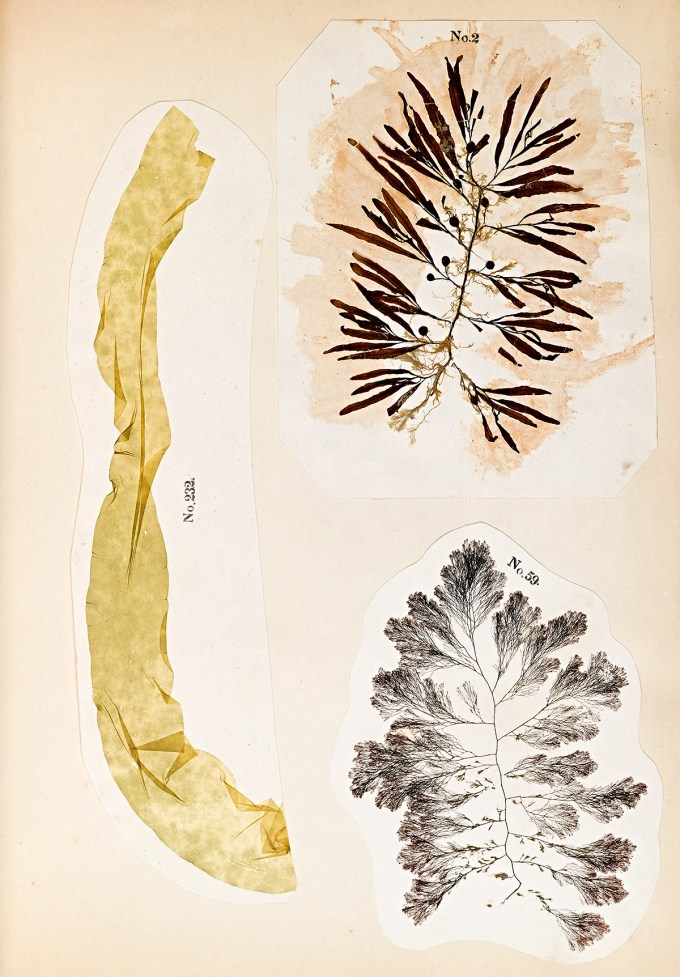

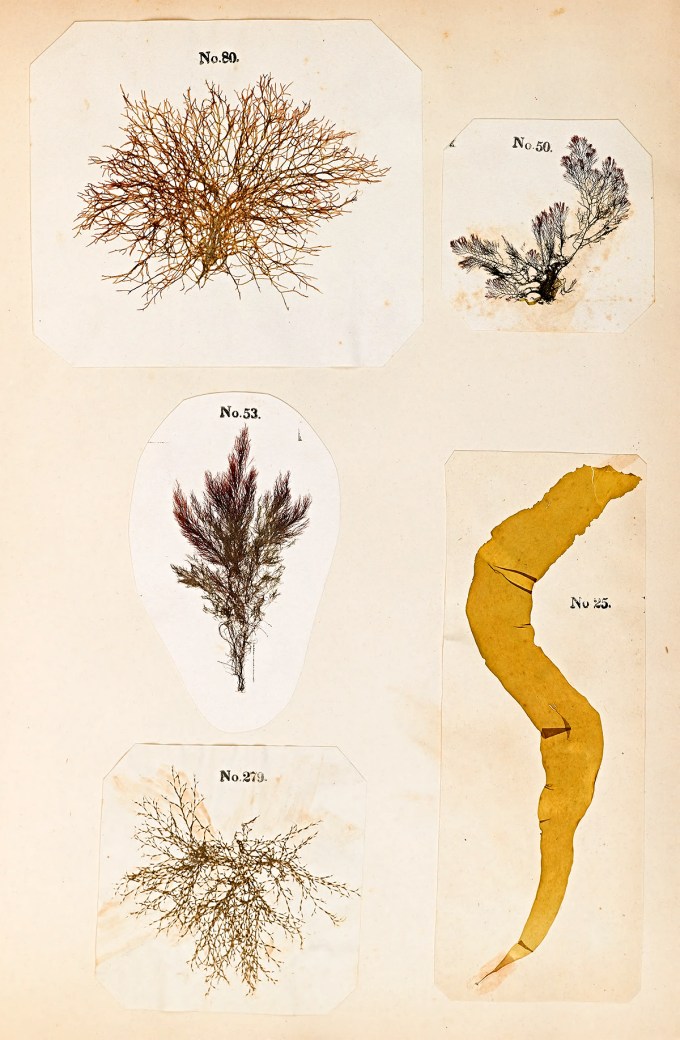

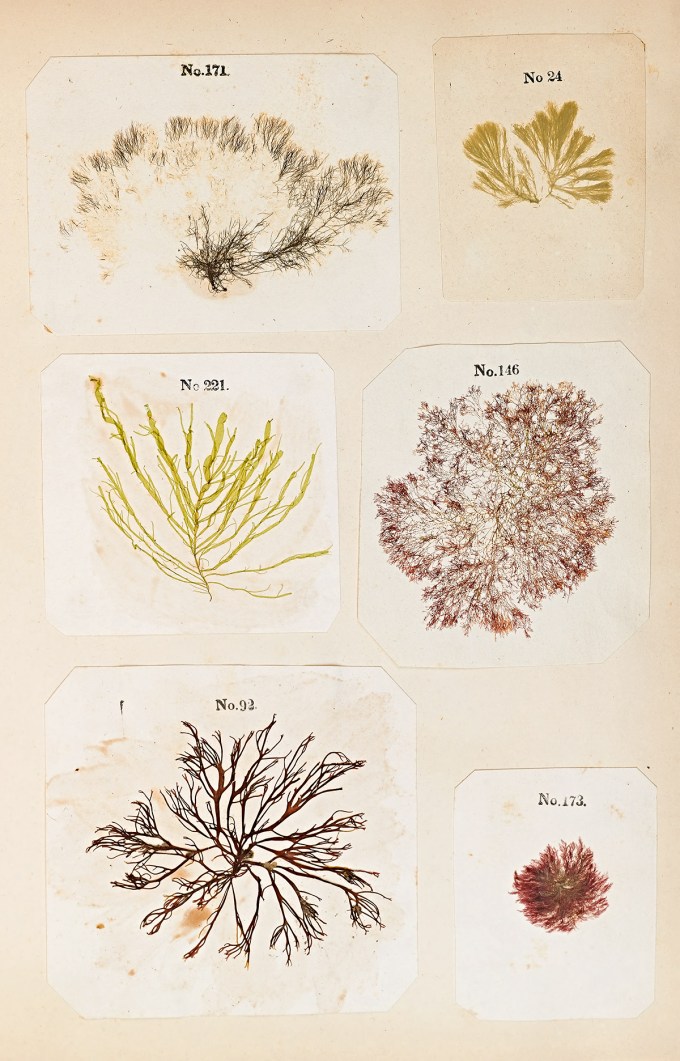

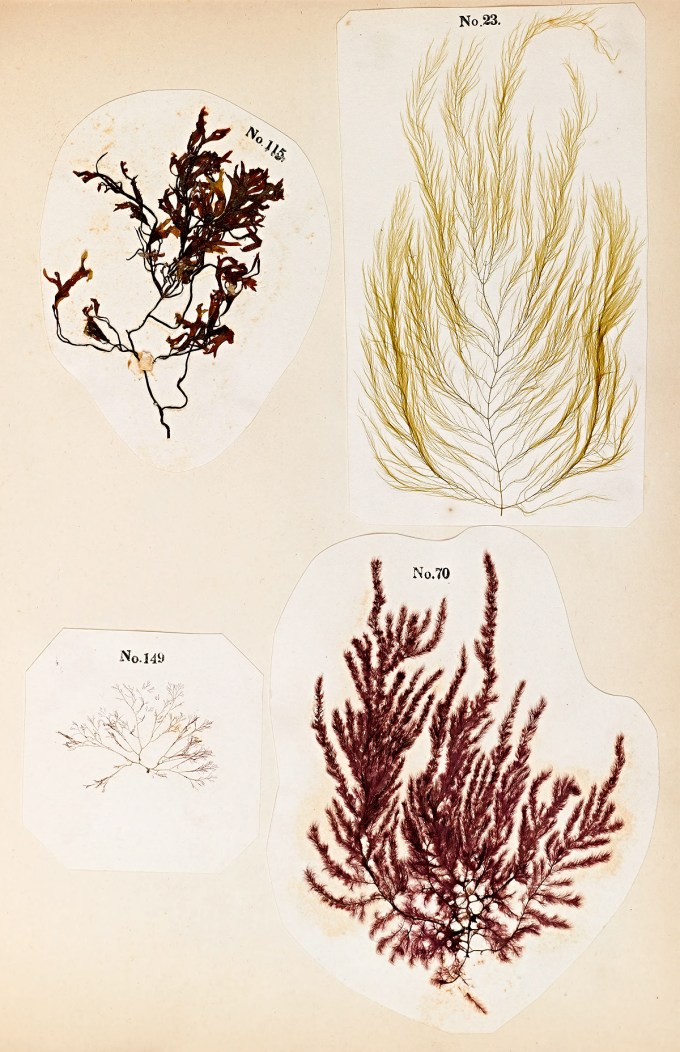

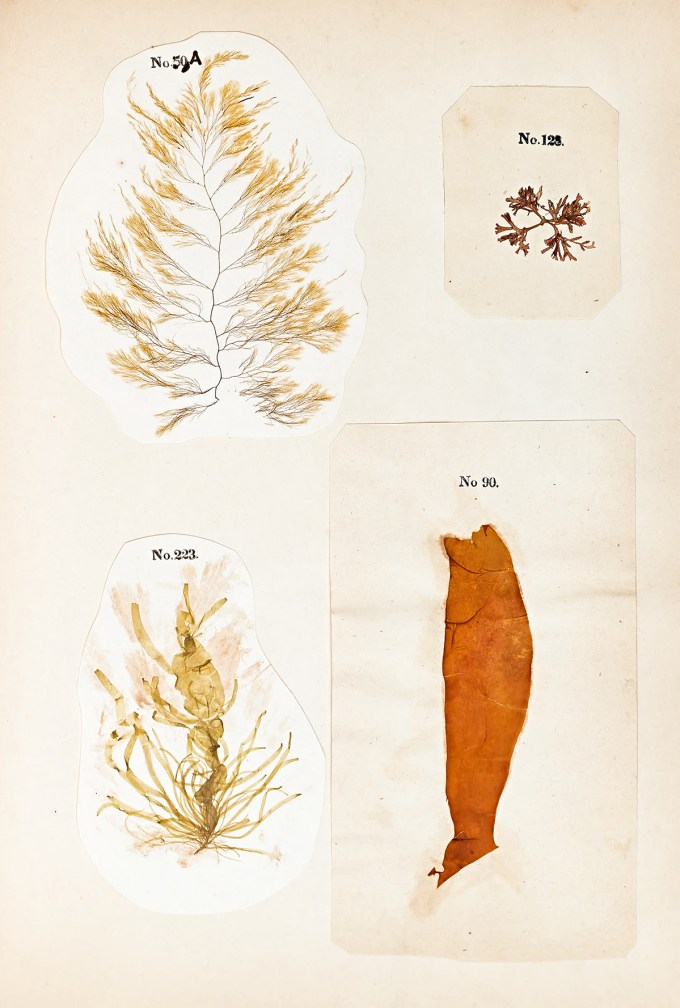

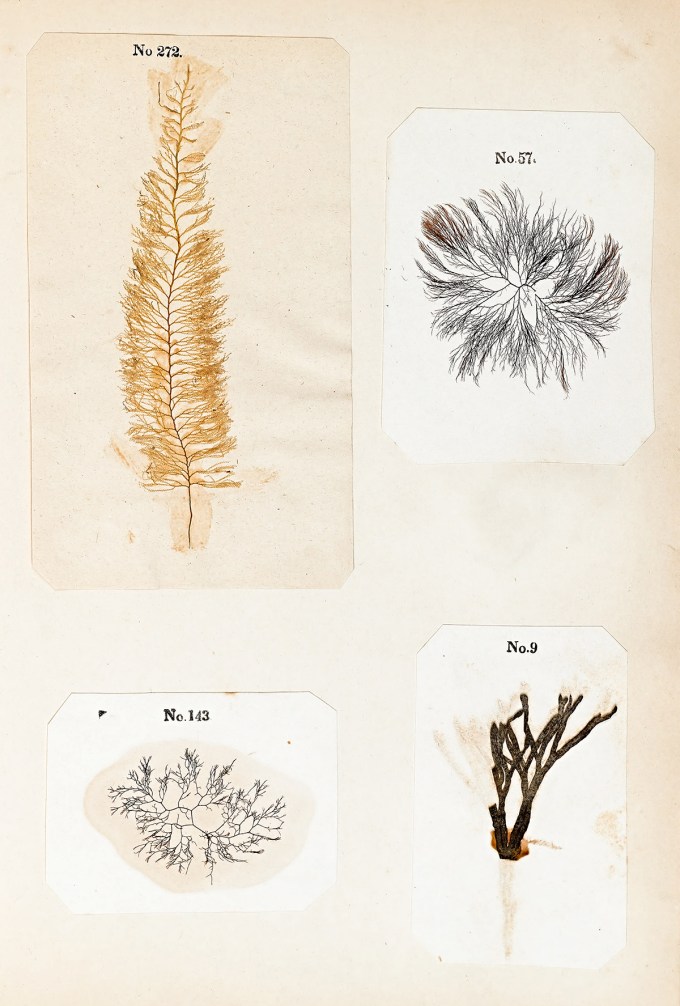

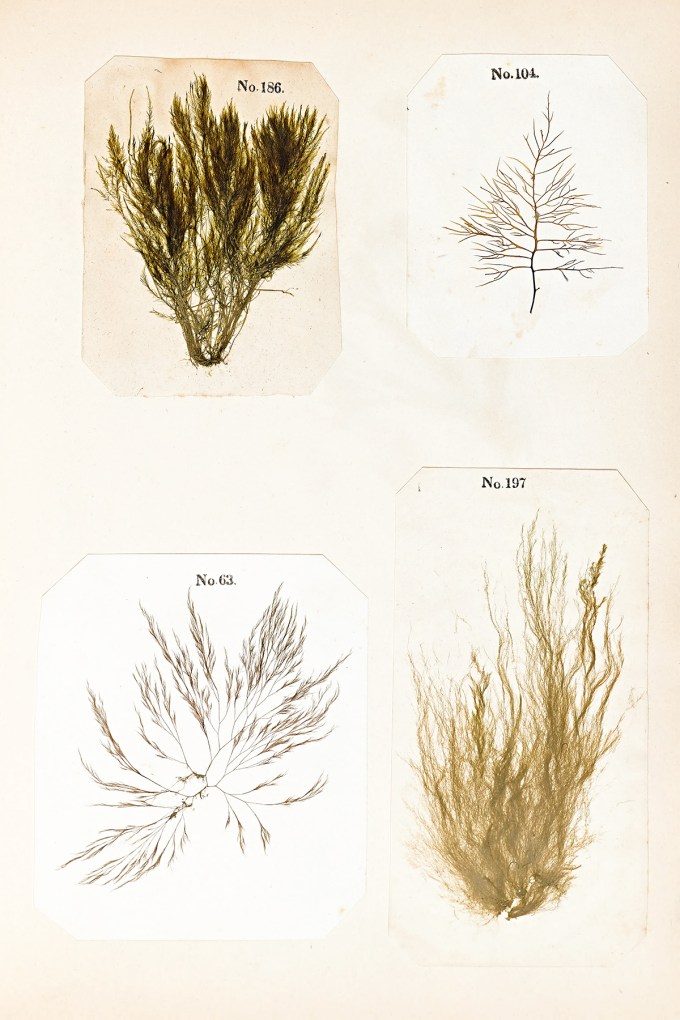

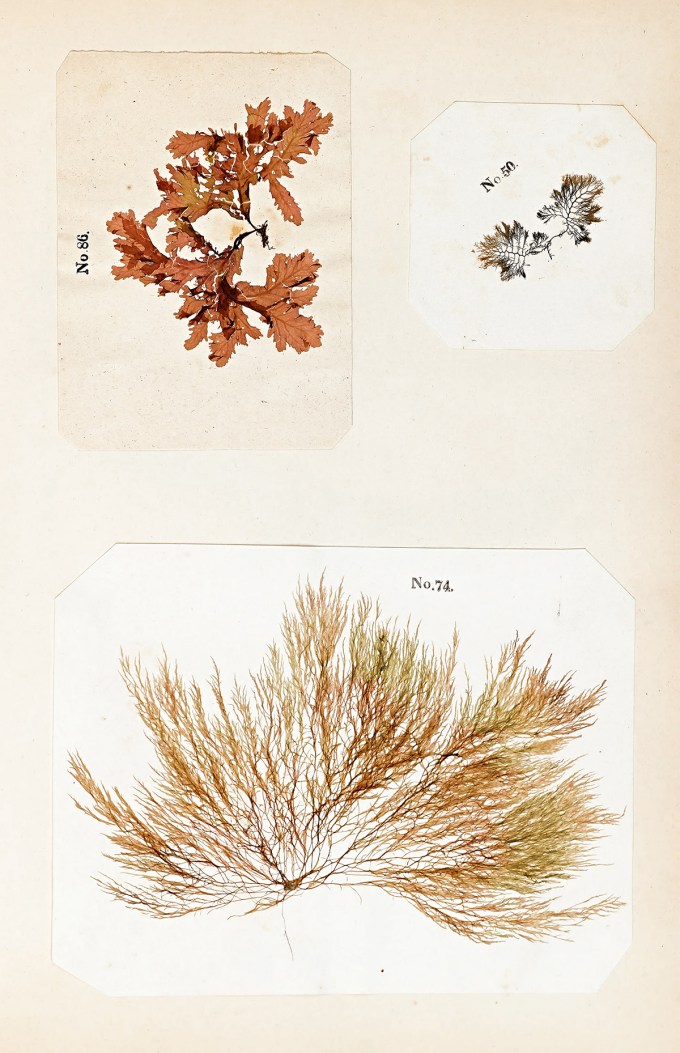

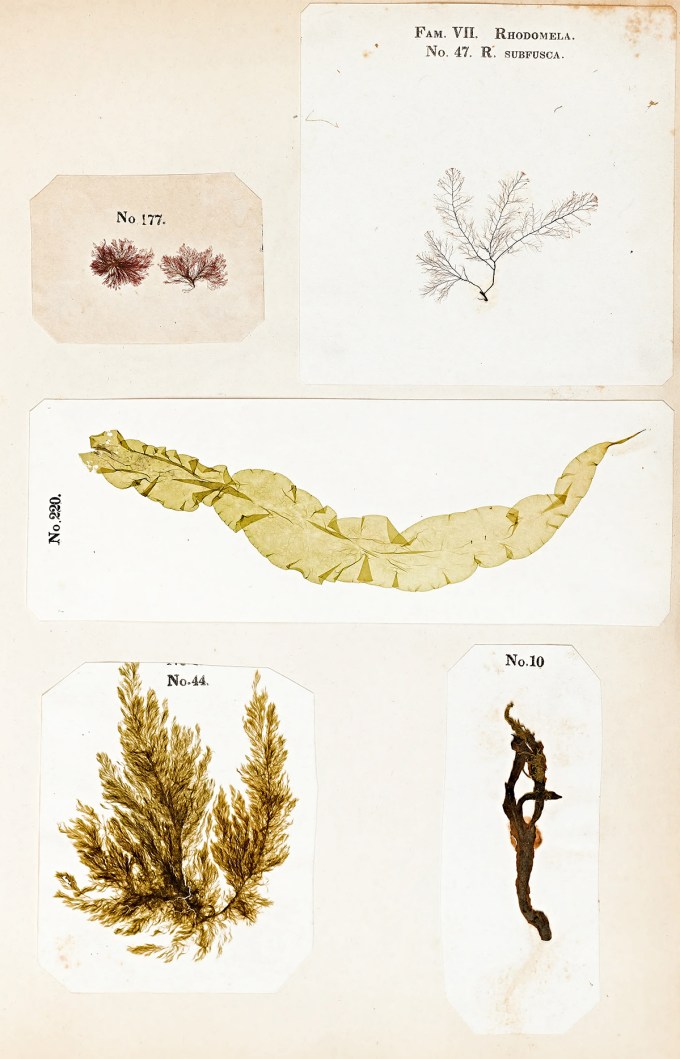

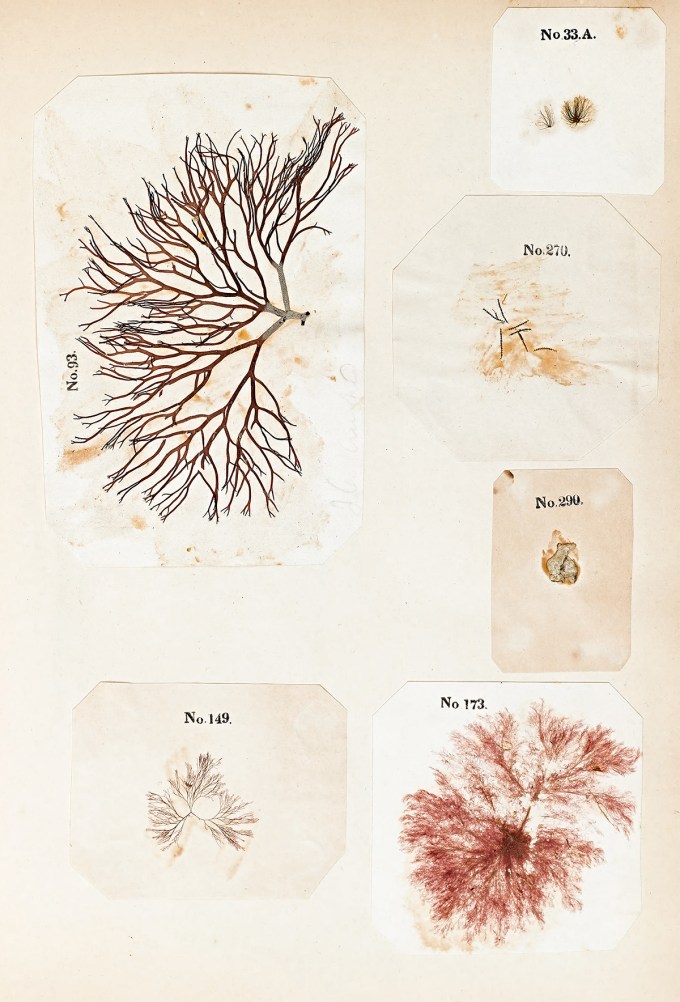

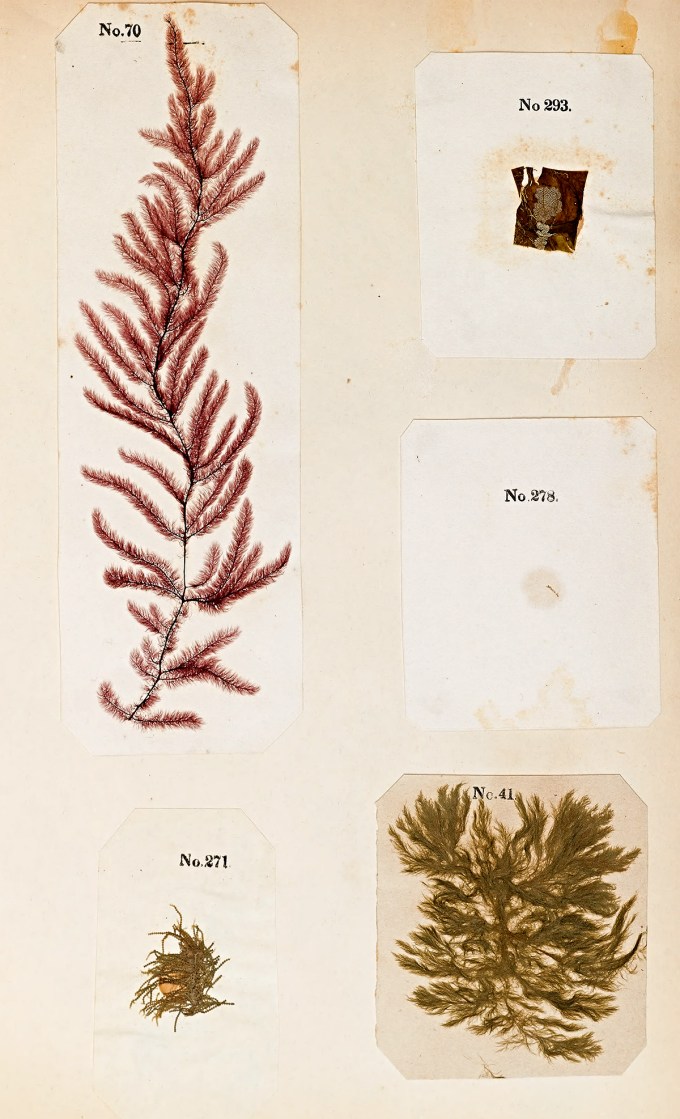

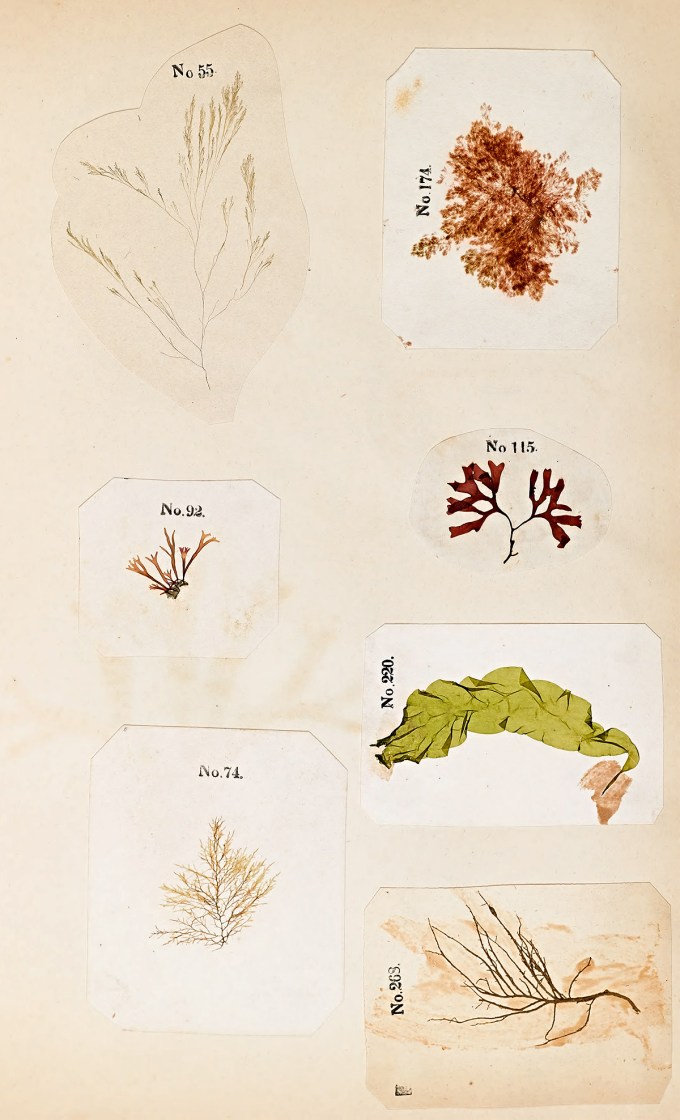

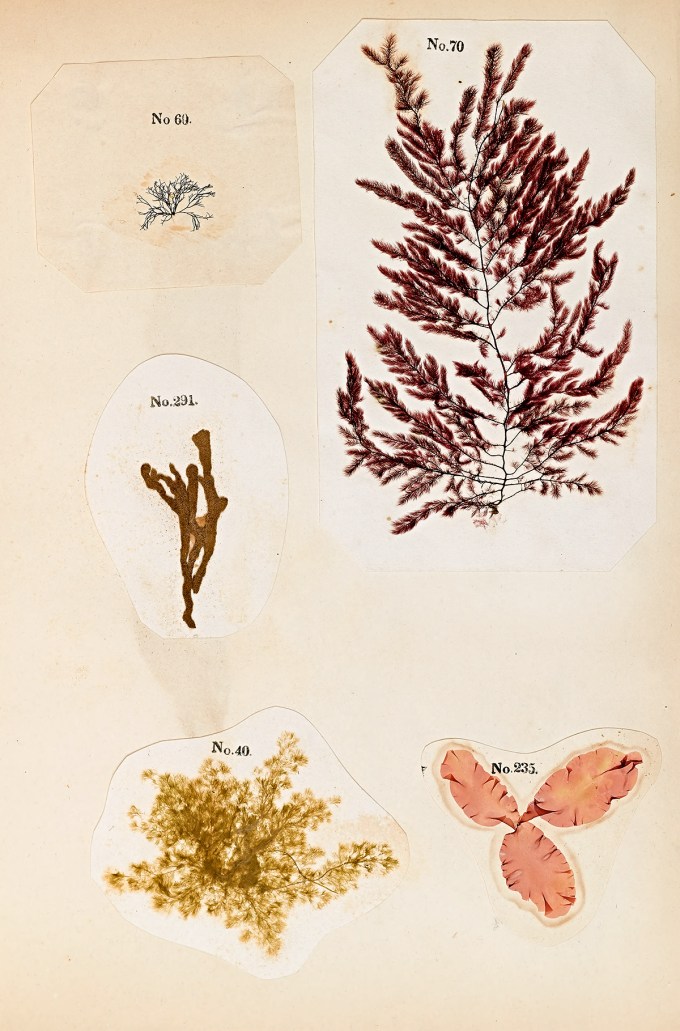

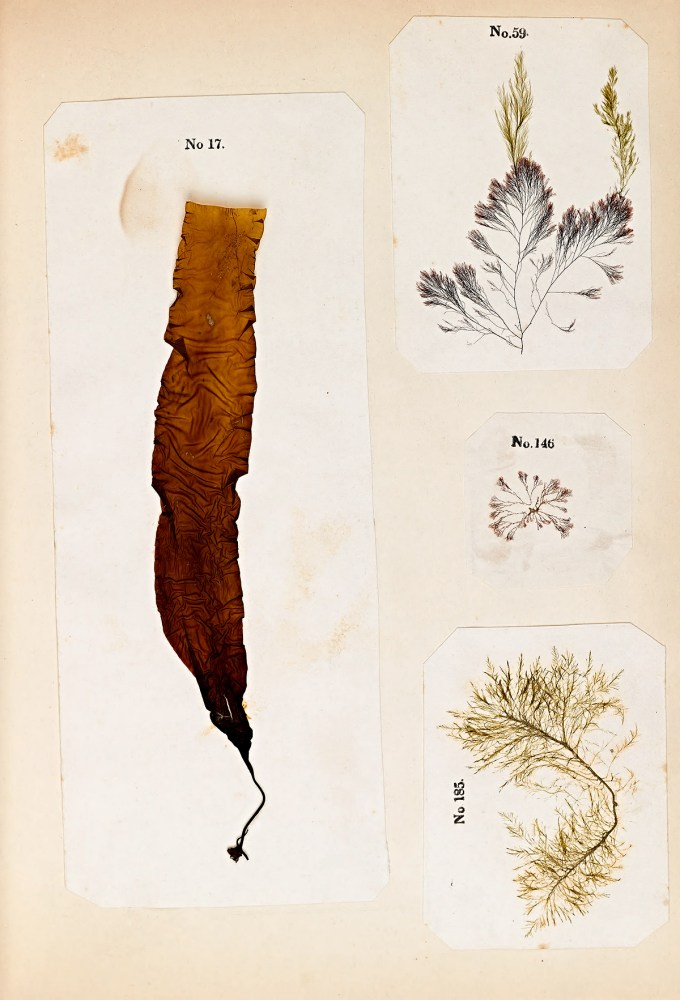

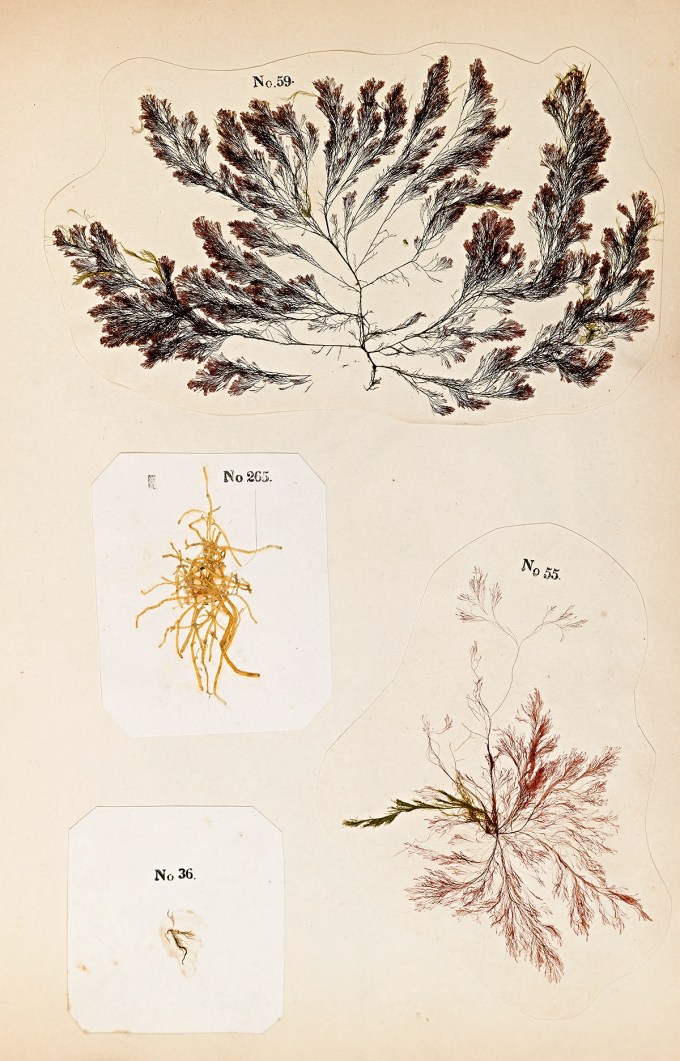

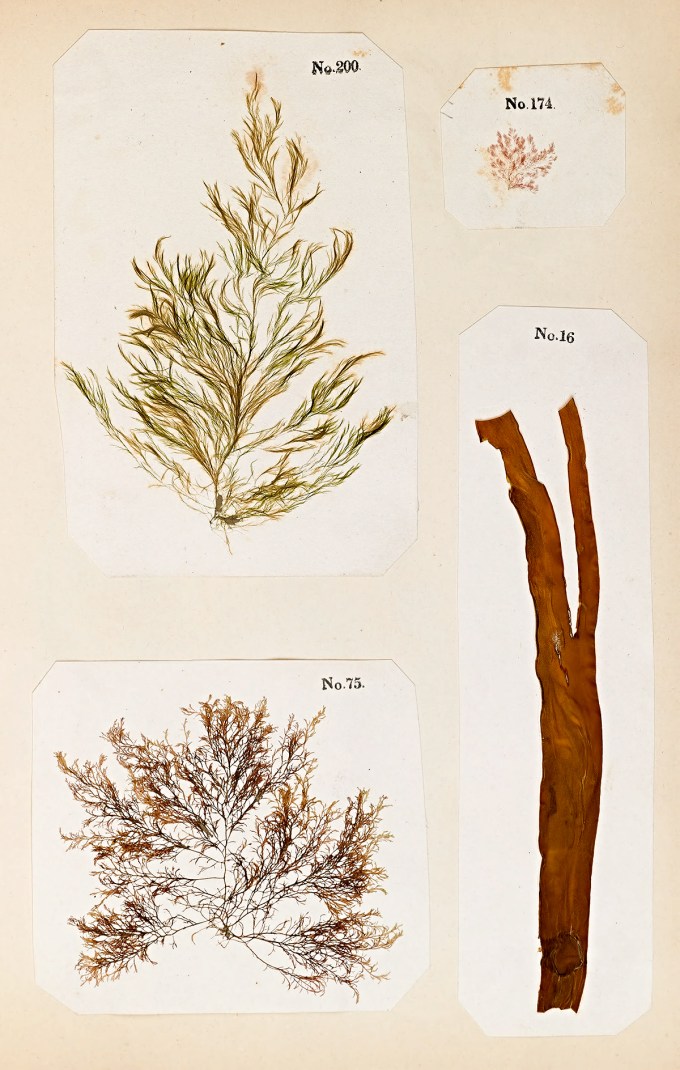

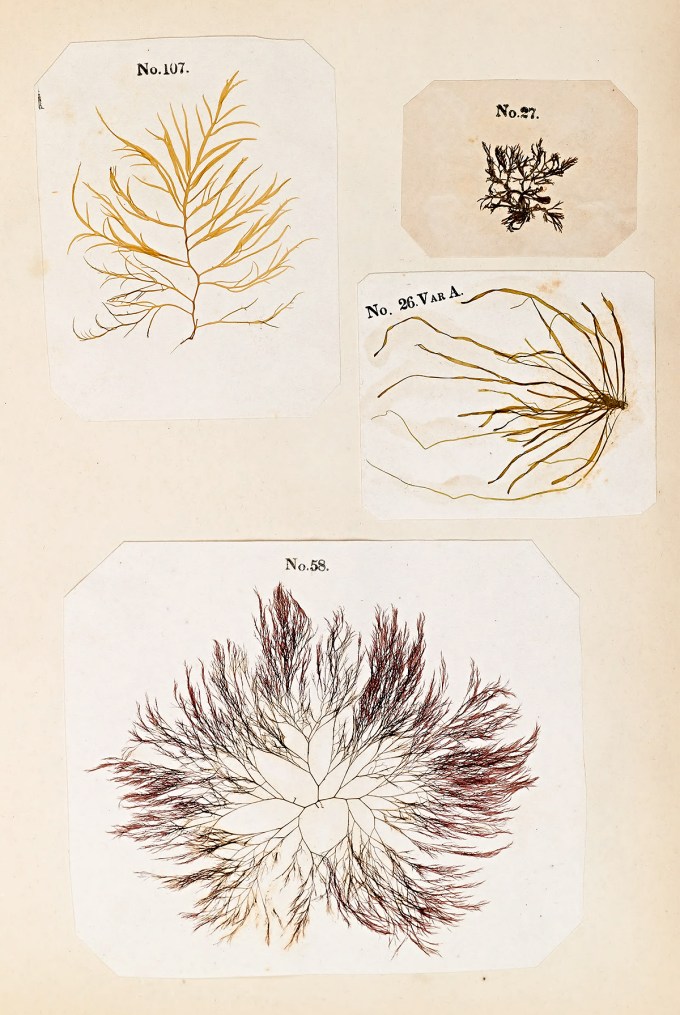

Unlike Anna Atkins, whose stunning cyanotypes prints of algae had rendered her the first person to illustrate a scientific book with photographs, Durant insisted on using real specimens in each handsomely bound copy of his labor of love. He set out to make fifty, but the endeavor — like anything worth making — turned out to be infinitely more time-consuming than anticipated: each specimen carefully pressed and glued, labeled with its scientific classification, and accompanied by a letterpress description. He barely managed a dozen copies, investing in them incalculable hours and more than two thousand dollars of his savings — the equivalent of about ,000 today.

We think of language as a vessel for conveying our ideas to other minds, a tool for framing what we see. But language is often the whetstone on which the mind hones its ideas about what it is seeing. Take the word weed. It denotes not something inherent to the plant it names but its utility to us — a term for any plant for which no human use has yet been discovered; a word whose meaning is malleable in time, rooted only in a consensual reality. The dandelion, long considered a weed, made its way into the world’s first illustrated encyclopedia of medicinal plants. A use. G.K. Chesterton looked at a dandelion and saw a sublime metaphor for wonder. Another use.

Epochs before the cult of kelp, not long after the invention of sushi on the other side of this pale blue dot, fifteen years before the new science of the sea birthed the term ecology, a passionate eccentric set out to render the loveliness of the underwater forest enchanting to the terrestrial eye.

Perhaps it was this uncommon contact with the grandeur of the ocean that awakened him to its otherworldly beauty; perhaps it was simply his polymathic ardor for science — he delighted in chemistry experiments, wrote treatises on astronomy, and planted mulberry trees to study silk-worms. But as a child of New York Bay, the mystique of the ocean remained his greatest love.

Complement Durant’s Algology with Concology — a stunningly illustrated Victorian encyclopedia of shells — and be sure to subscribe to Alie Ward’s reliably delightful kindred-spirited podcast Ologies, then revisit the story of the teenage Emily Dickinson’s extraordinary herbarium — a forgotten treasure at the intersection of poetry and science.

He had intended to sell the books for 0 each. But in the end, he couldn’t bear the thought of parting with something so precious in a mere monetary transaction, so he ended up giving them away — a handful to cultural institutions he felt would benefit from this unexampled survey of the sea, the rest to his three daughters and four sons. He only sold a single copy, in a fundraiser for sick and wounded Civil War soldiers. Fewer than five copies are known to survive.

One summer in his mid-forties, Durant decided to devote himself to the wondrous world of underwater plants. Walt Whitman was yet to compose his serenade to the “forests at the bottom of the sea” full of “branches and leaves, sea-lettuce, vast lichens, strange flowers and seeds.” The submarine wilderness was still largely a mystery, calling out to the poetic imagination far more readily than to science. No survey of North American algae existed at all. Durant felt called to bring to light the life-forms of “an unfathomable abyss, too wide, too deep, too vast for perfect exploration by human eye, or intellectual vision.”

Durant had done for American algae what the self-taught trailblazer Margaret Gatty had done for British algae two years earlier, and he had rendered them the way Emily Dickinson had rendered New England’s wildflowers another year before that: He had made an exquisite herbarium of the underwater wilderness.

Although winged by a personal passion, his was not a private album but a public book, both beautiful and informative, intended to cast on strangers the same spell the ocean had cast on him. He ended his preface with these prayerful words:

Radiating from the pages of Durant’s algae herbarium are the otherworldly blooms of some three hundred underwater photosynthetes, some previously unknown, all meticulously labeled and artfully arranged. Tender yet alien, belonging to a world for which we have no creaturely frame of reference, they confuse the imagination with their resemblance to things both familiar and surreal — the plumage of some mystical bird, the antlers of some Borgesian being, aerial maps of tributaries on some other planet.

Half an hour after sunrise at low tide, he would set out on foot — first to the rocky shore ten minutes from his house, and eventually along the length of the bay, collecting a cornucopia of algae. He dried the most delicate of them in the sun, wrapped the sturdier ones in sea lettuce, and hauled the morning’s findings home, where he began his ordinary workday of managing business affairs.