Complement with Bishop on why everyone should experience at least one long period of solitude in life and James Gleick reading her monumental poem about the nature of our knowledge, then revisit Amanda Palmer reading “Spell to Be Said Against Hatred” by Jane Hirshfield, “The Big Picture” by Ellen Bass, “Einstein’s Mother” by Tracy K. Smith, “Humanity i love you” by E.E. Cummings, “Hubble Photographs: After Sappho” by Adrienne Rich, and “Questionnaire” by Wendell Berry.

I lost my mother’s watch. And look! my last, or

next-to-last, of three loved houses went.

The art of losing isn’t hard to master.

Then practice losing farther, losing faster:

places, and names, and where it was you meant

to travel. None of these will bring disaster.

“The Gift of Losing Things.”

ONE ART

by Elizabeth Bishop

“How to Lose Things.”

Bridging this bittersweet unbidden moment with our longtime collaboration around poetry, I asked Amanda to record a reading of the poem as it made its way into her veins to live with her as it has lived with, and as it will live with you.

And finally, fifteen drafts later, “One Art.”

The art of losing isn’t hard to master;

so many things seem filled with the intent

to be lost that their loss is no disaster.

Alongside classics like Dylan Thomas’s “Do Not Go Gentle into that Good Night” and Sylvia Plath’s “Mad Girl’s Love Song,” “One Art” remains one of the greatest and most influential villanelles in the English language — sculptural masterworks of creative constraint, in which the virtuosity of language meets an exquisite mathematical precision in nineteen measured lines: five three-line stanzas and a final stanza of four lines, with the first and third line of the first stanza forming a refrain of alternating repetition across the remaining stanzas and then coming together into a chorus of a couplet in the closing verse. A haiku in the higher mathematics of meter.

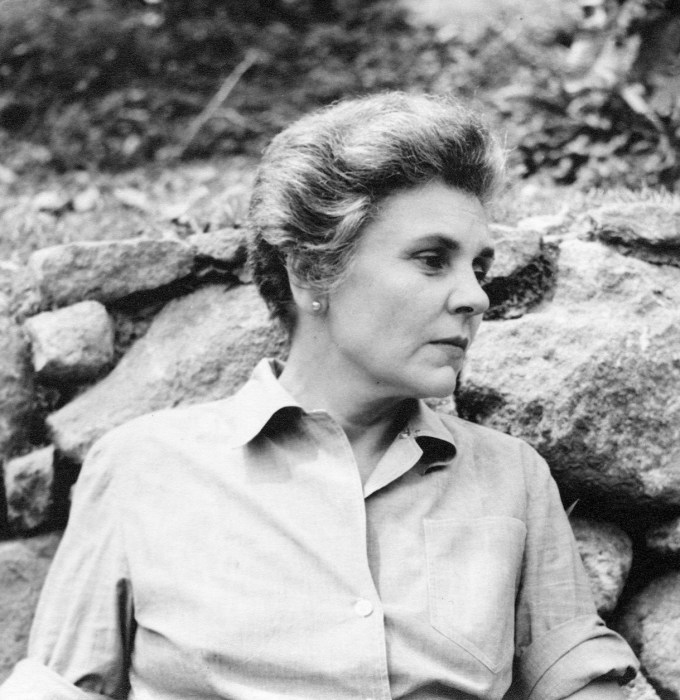

I will never forget the day I first encountered, in the midst of heartache, “One Art” by Elizabeth Bishop (February 8, 1911–October 6, 1979) — a poem I have lived with for years, a poem that has helped me live.

It is always a delight to witness someone you love discover something you have long loved, and so it was with immense delight that I watched my dear friend Amanda Palmer discover “One Art” in real time while we were smiling at each other screen-mediated and pandemic-strewn across opposite corners of the globe, each comforting the other’s recent losses. Having just come upon the poem via one of her patrons and not yet read it, she read it to me extemporaneously while I mouthed the words committed to heart. I watched ripples of deeply personal resonance animate Amanda’s face as she made her way through the poem — a poem universal and timeless, a beautiful and brutal emissary of elemental truth, written half a century ago out of the tumults of the poet’s personal life, out of her very particular time and place and circumstance, suddenly rendered the ultimate pandemic poem for this moment we share and the myriad personal losses within it — a testament to the young Sylvia Plath’s precocious observation that an artist never knows how their work will live in the world and touch other lives, that “once a poem is made available to the public, the right of interpretation belongs to the reader.”

I lost two cities, lovely ones. And, vaster,

some realms I owned, two rivers, a continent.

I miss them, but it wasn’t a disaster.

Bishop died not long after composing “One Art,” having requested the last two lines of another poem of hers as an epitaph:

—Even losing you (the joking voice, a gesture

I love) I shan’t have lied. It’s evident

the art of losing’s not too hard to master

though it may look like (Write it!) like disaster.

Lose something every day. Accept the fluster

of lost door keys, the hour badly spent.

The art of losing isn’t hard to master.

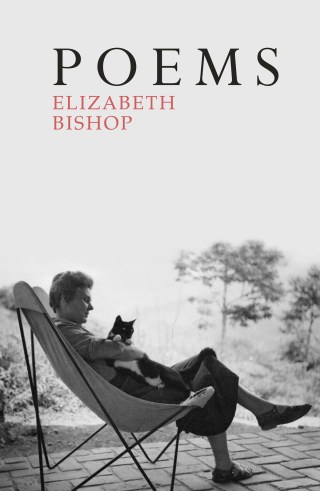

Composed when Bishop was sorrowing after a separation from her partner, Alice Methfessel, it is a staggering poem about love and loneliness, about the feigned fearlessness and forced levity we put on like an armor, like a costume, to cope with the terrifying heaviness of loss. Originally published in The New Yorker on April 24, 1976, twenty years after Bishop won the Pulitzer Prize and six years after she won the National Book Award, the following year it crowned the final book of poems published in Bishop’s lifetime and now lives on in her indispensable posthumously collected Poems (public library).

It is the only villanelle Bishop ever wrote. She surprised even herself. A spare and careful poet who published very few and very meticulous poems, she composed it with astonishing rapidity, feeling that it was “like writing a letter,” redrafting and retitling it over and over.

“The Art of Losing Things.”

All the untidy activity continues,

awful but cheerful.