If you are lucky enough to be an adult when you lose your parents — and, lest we forget, death is the emblem of life’s luckiness — complement it with Mary Gaitskill’s superb advice on how to move through life when your parents are dying, then revisit The Magic Box — a whimsical vintage children’s book for grownups about life, death, and how to be more alive each day.

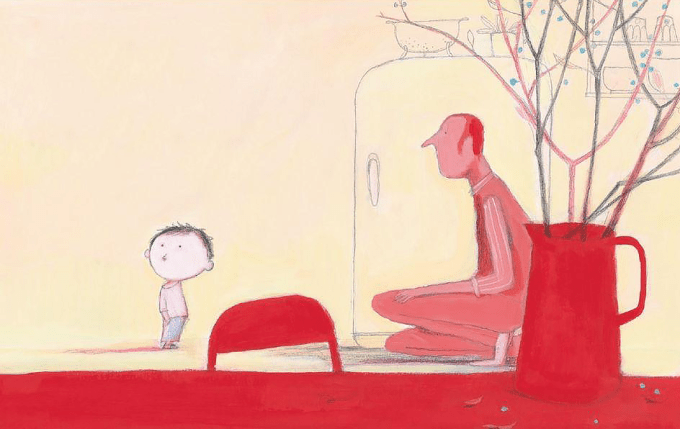

He won’t be able to manage without her.

Luckily, I’m still here, and I can explain everything to Dad.

I told him, “Don’t worry. I’ll take care of you.”

And I cried a little because I didn’t really know how to take care of a dad who’s been abandoned like this.

I could tell that he’d been crying, too —

he looked like a washcloth, all crumpled and wet.

I don’t really like seeing Dad cry.

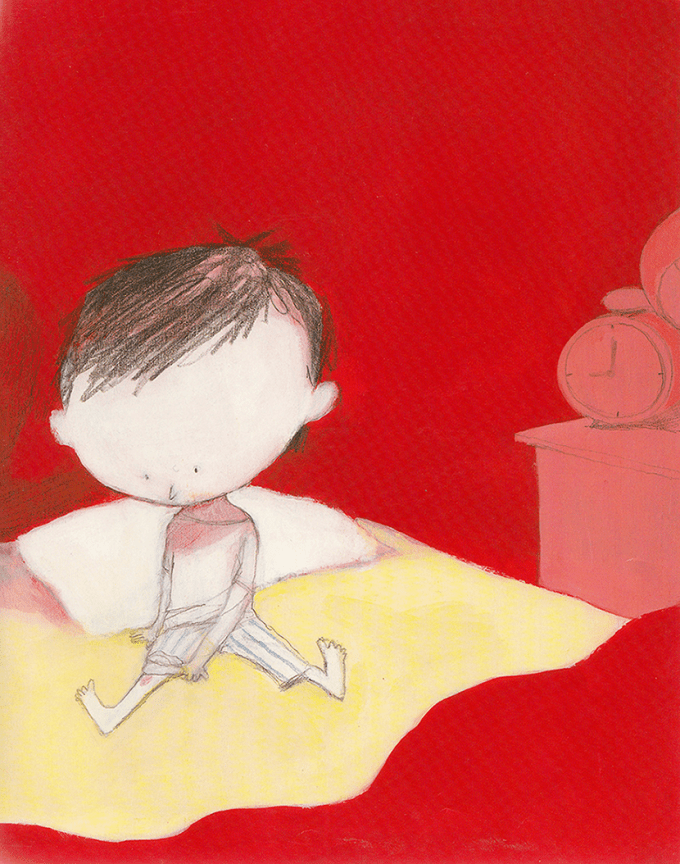

When I woke up this morning, everything was quiet. I couldn’t smell coffee or hear the radio. I came downstairs, and my dad said, “Is that you, honey?”

One day, while running in the garden, he cuts his knee and remembers how, whenever he got hurt, his mother would take him into her arms, tell him that it is only a scratch, tell him that he is too strong for anything to hurt him, and the pain would go away. Suddenly, there in the garden with the bloody knee, her voice returns.

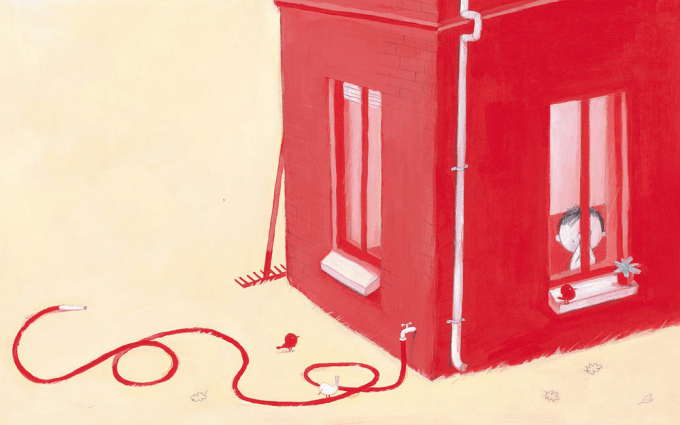

Anxious not to forget his mother, he plugs his ears to keep the sound of her voice from fading, shuts all the windows to keep her smell from leaving.

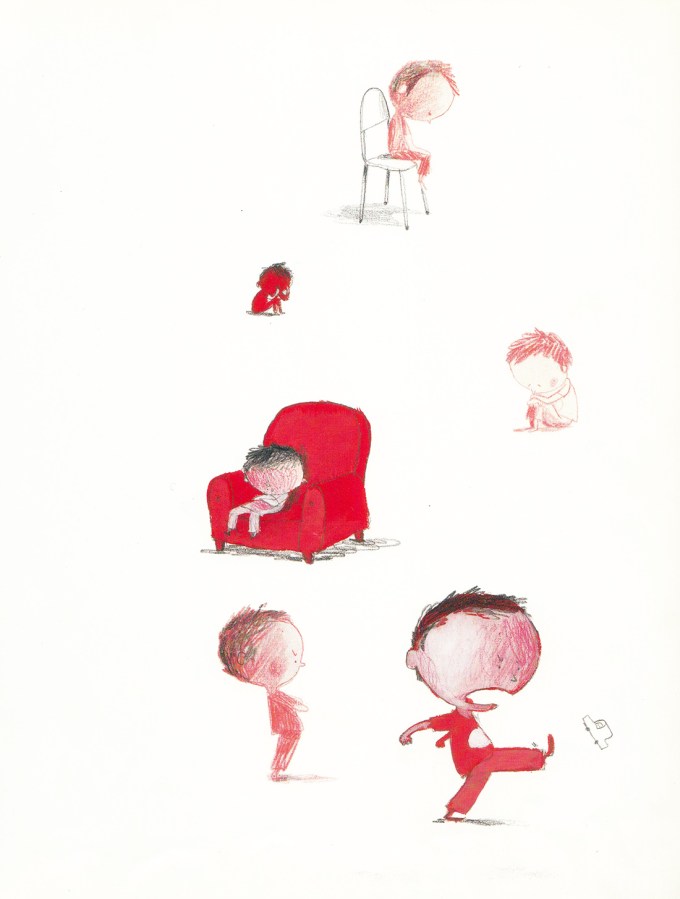

Dad yells at me because it’s summer, because it’s too hot, and because he doesn’t know how to talk to me anymore.

I think it hurts him to look at me because I have my mom’s eyes.

As the little boy and his father face the initial shock of incomprehension, we see how the hard problem of selfhood softens, slackens, seems to come undone in the wake of loss.

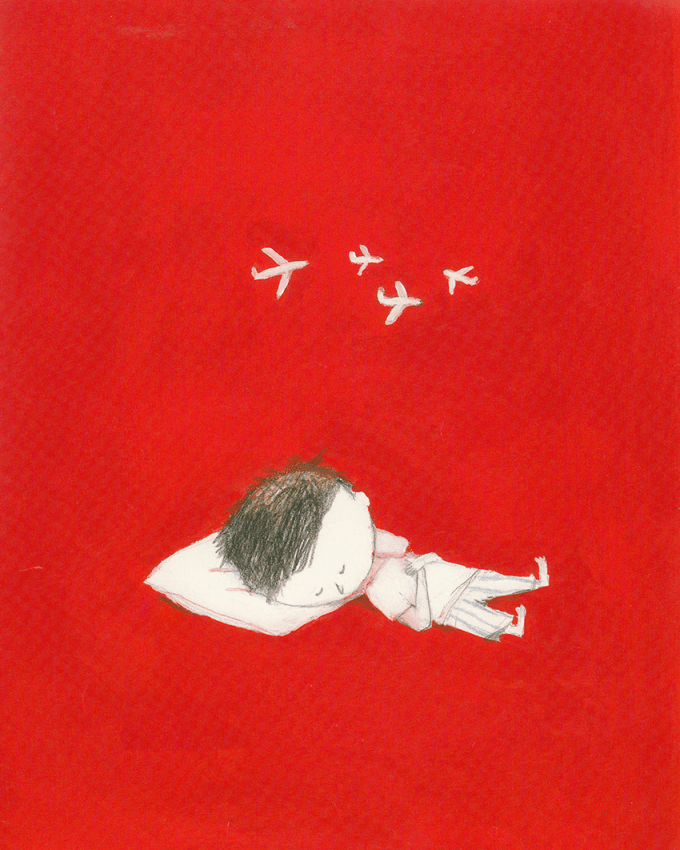

I lie back, my hands on my chest. My heart beats quietly, peacefully, and it lulls me to sleep.

It helps, this simple gesture bridging the body and the soul.

Soon, grandma — his mom’s mom — arrives. He worries that he now has “two sad adults” to take care of while tending to his scab.

But just as he worries that his grandma would think him crazy, she walks over and puts her hand, then his little hand, on his heart.

Soon, the little boy is running everywhere to feel his heart beating.

A century after Rilke wrote that “death is our friend precisely because it brings us into absolute and passionate presence with all that is here, that is natural, that is love,” the story radiates the subtle and sensitive reminder that love, though its external objects may be made of atoms, is an inner abstraction that exists entirely in our own hearts, a figment of our own consciousness. And so, in some deep sense, our loved ones — both living and dead — are figments of our love, existing only relative to our consciousness of them.

I know only three side-doors to the cathedral of consciousness, through which we can bypass the bewildered mind to enter the heart of the most unfathomable, shattering, and universal human experiences, emerging a little more whole: poetry, children’s books, and Bach.

“She’s there,” she says, “in your heart, and she’s not going anywhere.”

For a second I think I might cry, but I don’t.

When grandma swings the windows wide open to relieve the heat, the little boy finally lets loose feelings he has been numbing with the tender illusion of caring for the grownups.

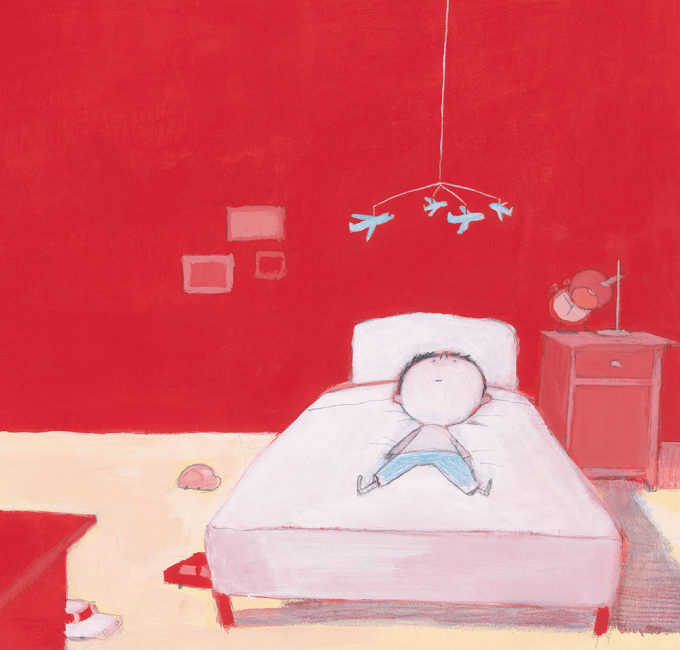

One night, in bed under the covers, he brushes the wounded knee with his finger and feels the skin smooth and new. Sitting up to take a look, he discovers that the scab is gone, transformed into a scar without his noticing.

Grandma moves through the house in a silent stupor, “like she’s searching for something or someone,” embodying Nick Cave’s observation of the central paradox of loss: how when a loved one dies, “their sudden absence can become a feverish comment on that which remains… a luminous super-presence.”

He shouts “It’s me!” from the top of the stairs, just to make his dad smile, and his dad does smile, and opens his arm, and his small son runs into them, feeling his beating heart.

That’s too much for me. I shout and cry and scream. “No! Don’t open the windows! Mom’s going to disappear for good…” And I fall and the tears flow without stopping, and there’s nothing I can do and I feel very tired.

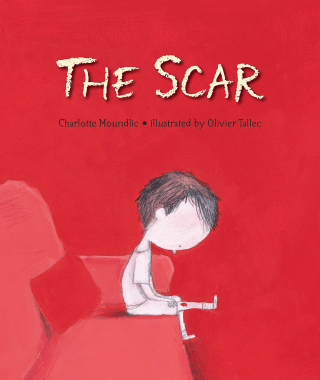

The Scar is a lovely addition to my evolving bookcase of unusual picture-books about making sense of loss.

Grandma eventually leaves. As the days unspool for the loom of time — the time-outside-time into which loss thrusts us — he begins smelling coffee again downstairs and hearing the radio forecasting clement weather.

No human experience is more shattering than the vanishing of a loved one into “the drift called ‘the Infinite,’” in Emily Dickinson’s haunting phrase — especially a parent, and especially if one is still a child when the unfeeling hand of chance smites.

I said, “No, no, it’s not me,” which I thought was pretty funny, but then I noticed that Dad wasn’t laughing. He smiled a very small smile, and said, “It’s over.” and I pretended I didn’t understand.

I thought that was a silly question, because other than Mom, who was too sick to get out of bed anymore, and Dad, who was the one asking the question, I was the only one in the house.

After moving through the initial wave of fury at the universe — the kind of fury that, if not fully given the feeling-space it demands and not properly integrated, can lodge itself into the marrow of being as a lifetime of pent up rage at life — the boy takes it upon himself to salve his father’s sorrow.

French author Charlotte Moundlic swings the side-door open into a portal of tenderness and healing with The Scar (public library), illustrated by one of my favorite picture-book artists — Olivier Tallec, who also illustrated the exquisite and kindred-spirited Cry, Heart, But Never Break.

Aching to hear it again, he waits until a tiny scab forms, then scratches it off again, trying not to cry, trying to invoke his mother’s voice. The scab becomes his secret way of keeping her alive — an embodied memory, a testament to poet Meghan O’Rourke’s observation, upon losing her own mother, that “the people we most love do become a physical part of us, ingrained in our synapses, in the pathways where memories are created.”

Days pass, nights. The boy finds himself unable to sleep. A stomachache gnaws at him. His inability to take care of his dad gnaws at him.

Mom died this morning.

It wasn’t really this morning.

Dad said she died during the night,

but I was asleep during the night.

For me, she died this morning.