It is marvelous the quickness with which nature responds. Where there was once little, we have abundance.

The swampy hog lot below the Big House had been transformed into a garden with a clear spring stream running through it that no longer dried up in the summertime. Concord, Niagara, and Golden Muscat grapevines clambered over the garden fences. In the shade, Bromfield let healthy brambles of raspberries and blackberries run wild — never cultivating them but just mulching once a year. Where once there was a gullied hillside, he now saw flowering shrubs and rich fields. When it rained, the water no longer rushed down the hills in brown torrents that cut the earth. The contoured rows of crops hugged the landscape. In the apple orchard, a thick layer of sod grass had grown up around the old trees. And new trees had been planted: peaches, plums, and pears. Bumblebees, working “in platoons,” pollinated the fruit trees as well as the pastures of clover and alsike. He planted a row of locust trees to feed the bees — and to pour more nitrogen into the soil (since locusts are also a legume). He loved the smell of their blossoms that drifted into the Big House. He loved seeing muskrats swim across the pond in the moonlight. He loved standing in a field of corn in midsummer and listening for the “faint crackling sound” as “the stalk increases its circumference cell by cell.”

A good farmer, Bromfield said, is “the happiest of men for he inhabits a world that is filled with wonder and excitement over which he rules as a small god.”

The word ecology had been coined less than a generation before his birth; Rachel Carson was yet to wrest it from academic obscurity and make it a household word. At a time when the phrase “organic food” would have baffled with its Frankensteining of chemistry and cuisine, Louis Bromfield envisioned a time when the makers of consumer packaged goods would use a special label verifying that their foods were untouched by chemicals. Before the term “sustainable agriculture” meant anything to anyone, he built and passionately tended to an organic permaculture farm, sustainable and regenerative, not in exploitation of but in relationship with the land and its living ecosystems.

There were beehives to pollinate the orchards and pastures. There was an enormous diversion ditch contouring the surrounding hillsides to catch floodwater and release it slowly instead of razing every living thing in its path. There was a meticulous crop rotation program, alternating between species like corn, which deplete the soil of nitrogen, and species like alfalfa, which replenish it. Cows grazed in the fields to furnish most of the needed nitrogen with the natural byproducts of their metabolism, and other essential nutrients were added by introducing limestone and phosphorus into the ground. Cover crops of legumes shielded the vulnerable top fields from erosion and were often intentionally left to compost into the earth as “green manure” further enriching the soil. Grasses and green hay were planted as soil-binding on the steepest slopes. A hedge of new trees was planted along the perimeter of the overgrazed forest to keep the cows away and let the old growth recuperate.

He saw her because he too was awake to these delicate wonders of nature and the even more delicate relationship between them, which enchanted him into pioneering a different way of relating to the land. He would use his celebrity to seed that private passion into the heart of the public, fomenting a whole new consciousness.

“We forget that nature itself is one vast miracle transcending the reality of night and nothingness,” Loren Eiseley wrote in his exquisite 1960 meditation on nature, human nature, and the meaning of life. “We forget that each one of us in his personal life repeats that miracle.” Six years earlier, Rachel Carson had invited an elemental remembering as she considered our spiritual bond with nature: “Our origins are of the earth. And so there is in us a deeply seated response to the natural universe, which is part of our humanity.”

Hayman writes of this wondrous transfiguration:

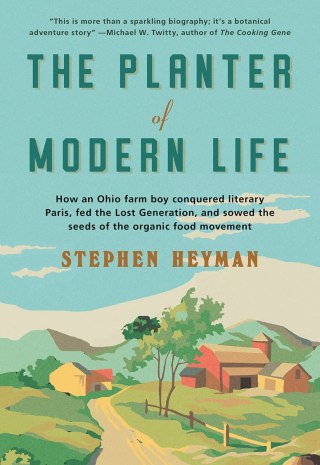

Bromfield’s far-reaching vision and his disarming devotion to it come alive in Stephen Heyman’s wonderful biography — of a person, of an idea, of an epoch — The Planter of Modern Life: How an Ohio Farm Boy Conquered Literary Paris, Fed the Lost Generation, and Sowed the Seeds of the Organic Food Movement (public library).

One of Bromfield’s fictional protagonists contoured the future he seeded — the future that is only just cusping on the horizon of our present as a hopeful fact — in a passage from his 1933 autobiographical novel The Farm:

On his unexampled Malabar Farm in Ohio — so famed that it became the setting of the opening scene of The Shawshank Redemption — Bromfield complained the way all artists do: by creating. “Most of our citizens do not realize what is going on under their very feet,” he rued. At Malabar, everything under and over and between was one cohesive symphony of sustainability, for the enduring harmony of which he felt — and was — responsible, and rapturously so. Out of that responsibility, Louis Bromfield built an astonishing interleaved wonderland an epoch ahead of its time.

Some day… there will come a reckoning. The country will discover that farmers are more necessary than traveling salesmen, that no nation can exist or have any solidity which ignores the land. But it will cost the country dear. There’ll be hell to pay before they find out.

[…]

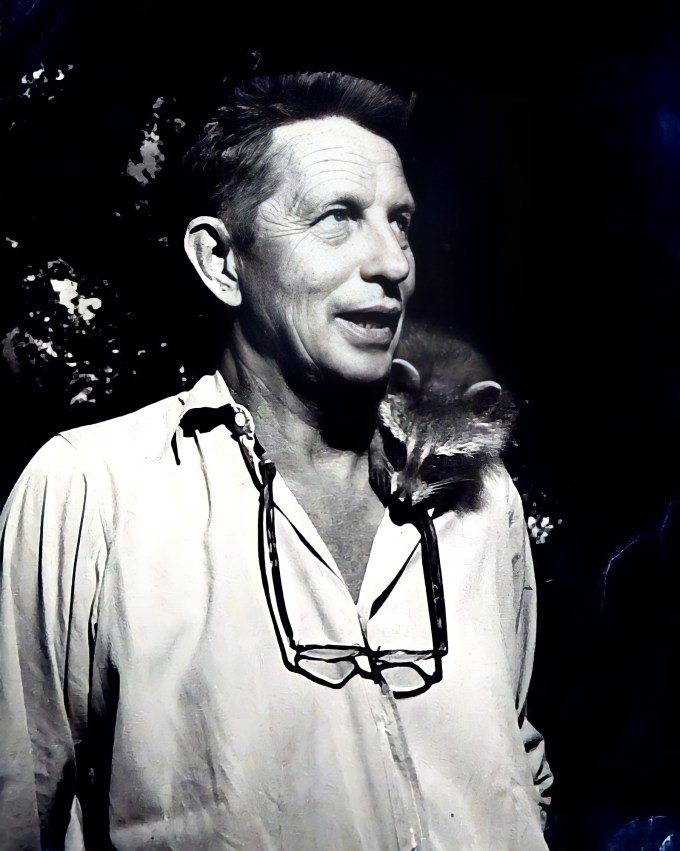

Louis Bromfield — a middle-class Midwesterner who had worked as an ambulance driver during the First World War and had spent the 1920s living in a rented old rectory in Paris with his typewriter and his giant gramophone — was Gertrude Stein’s favorite American novelist and the Lost Generation’s favorite Ivy League dropout. He was Doris Duke’s lover and Humphrey Bogart’s best man. He inspired Wendell Berry and became a model for Joel Salatin. E.B. White winked at him in a poem. Edith Wharton felt more seen by him than by anyone else — seen for something invisible and incommunicable to others, something “tremblingly and inarticulately awake to every detail of wind-warped fern and wide-eyed briar rose.”

My travel, my experience — nothing I have ever done has given me nearly as much satisfaction as this bit of land and what we have been able to do with it. I take deep pleasure in going out every morning and seeing the miraculous changes which have happened, and which are happening, and which will go on happening until the end of our lives.

Bromfield himself was awed by how these measures had transformed the land in only a couple of years:

A generation before Carson and Eiseley, humanity found an unlikely champion of that elemental bond with our origins in Louis Bromfield (December 27, 1896–March 18, 1956), who regarded his Pulitzer Prize and Hollywood’s adulation as satisfactions far inferior to the infinite gladnesses of the garden, the farm, the irrepressible life of nature that he both nurtured and was nurtured by.

The Planter of Modern Life is an inspiriting read in its entirety — the kind that restores your faith in the humans that make humanity. Complement it with this century-old field guide to wonder by another visionary far ahead of her time, who lived even before Bromfield and who laid the groundwork for the Youth Climate Action movement of our time, then revisit the story of how Rachel Carson awakened the modern ecological imagination.

But Bromfield saw this work as far more than the work of pleasure — he saw it as a moral obligation. Two days before Pearl Harbor, and an epoch after Walt Whitman admonished that “America, if eligible at all to downfall and ruin, is eligible within herself, not without,” Bromfield told the audience at a war rally that “we are in more danger of destroying ourselves” than of “being destroyed” — that America’s grimmest war was the one it had already launched on the environment. (The term itself is grimly alienating, implying that we are merely surrounded by nature and denying that we are nature, too — a term we still use, the eradication of which might one day mark our true awakening to our natural bond with the rest of nature.)

Bromfield was animated by the recognition that farming is not only supreme training ground for self-reliance — a practice powered by the selfsame qualities one needs in times of crisis and turmoil — but a spiritual practice that trains the soul on humility, on integrity, on compassion: seeds of flourishing, the succulent fruits of which are readily available to the farmer year-round. Heyman writes:

Dorothy Parker, E. B. White, Archibald MacLeish: they all had farms at one time or another. But they were amateurs, dabblers, at best gentleman or lady farmers who treated their rural seat more as backdrop than subject. Bromfield was different. He would make agriculture into literature in a way that none of his forebears or contemporaries had. He was the first major writer to give himself over completely to the problems and possibilities of agriculture, to get down into the dirt of it, to become a modern farmer. Farming became for him a calling, a platform, almost a religion. He wanted not just to farm for himself but to change the idea of what the farmer was or could be. His celebrity, his creativity, his money — all of it would eventually go into the compost pile.

Louis Bromfield was conducting a chorus of aliveness, in which everything sang.

Nothing — not his Pulitzer Prize, not the ardors of Paris, not Hollywood’s argent flatteries — was more rewarding to him:

Later in life, Bromfield would give his definition of a “good farmer,” and it was both lofty and long. A farmer, he said, should be “a horticulturalist, a mechanic, a botanist, an ecologist, a veterinarian, a biologist and many other things.” He should have an open mind that was “ready to absorb new knowledge and new ideas.” But knowledge was “not enough.” He needed, most importantly, two traits which “could not be acquired,” which were “almost mystical qualities.” These were “a passion for the soil” and an “understanding and sympathy with animals.” In other words, Bromfield thought, a good farmer needed to be a little teched.