Now here is a faith a person of warmth and wakefulness can get behind:

A generation after the trailblazing astronomer Maria Mitchell wrote in her diary that “every formula which expresses a law of nature is a hymn of praise to God,” Burroughs observes:

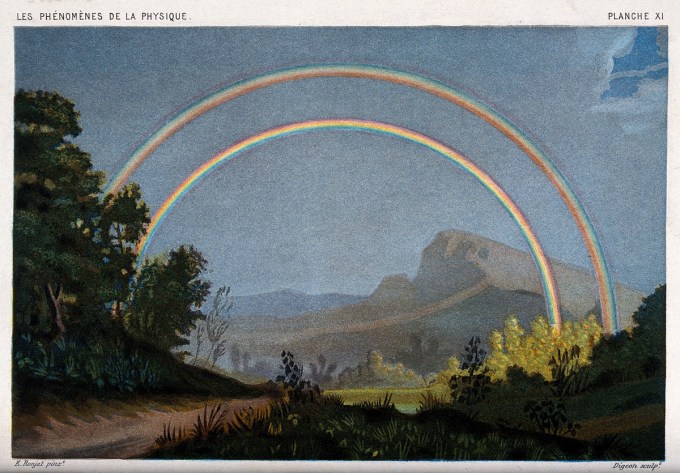

The naturalist or naturist… sees the cosmic forces only; he sees nothing directly mindful of man, but man himself; he sees the intelligence and beneficence of the universe flowering in man; he sees life as a mysterious issue of the warring elements; he sees human consciousness and our sense of right and wrong, of truth and justice, as arising in the evolutionary sequence, and turning and sitting in judgment upon all things; he sees that there can be no life without pain and death; that there can be no harmony without discord; that opposites go hand in hand; that good and evil are inextricably mingled; that the sun and blue sky are still there behind the clouds, unmindful of them; that all is right with the world if we extend our vision deep enough; that the ways of Nature are the ways of God if we do not make God in our own image, and make our comfort and well-being the prime object of Nature… He that would save his life shall lose it — lose it in forgetting that the universe is not a close corporation, or a patented article, and that it exists for other ends than our own. But he who can lose his life in the larger life of the whole shall save it in a deeper, truer sense.

[…]

An epoch before W.H. Auden — the son of a physicist and the survivor of two world wars — could write of “stars that do not give a damn” in one of his most devastatingly beautiful and humanistic poems, Burroughs considers what many call “Providence,” but we might equally call chance. In place of the narcissistic self-delusion embedded in all notions of a god dispensing personal partialities, Burroughs celebrates the sober transcendence of accepting an impartial universe:

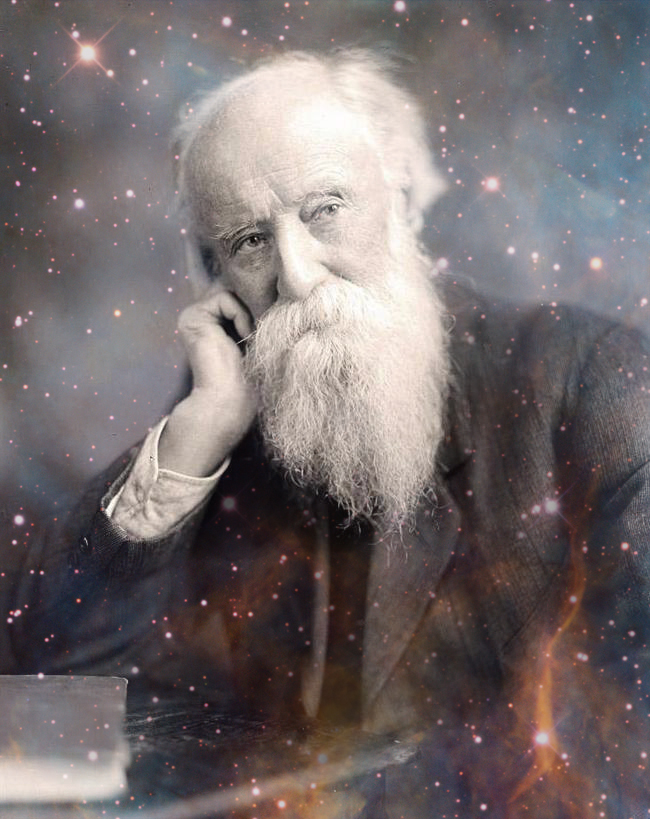

For those of us who stand with Simone de Beauvoir on the question of religion and take to poet Diane Ackerman’s answer to spirituality,there is hardly a lovelier gospel than “The Faith of a Naturalist” by John Burroughs (April 3, 1837–March 29, 1921) — one of the dozen exquisite pieces in his 1920 collection Accepting the Universe: Essays in Naturalism (public library | public domain).

“At bottom the whole concern of both morality and religion is with the manner of our acceptance of the universe,” William James wrote in the first years of the twentieth century as he considered the shifting place of spirituality in a science-illuminated world. “Do we accept it only in part and grudgingly, or heartily and altogether?”

Life is here because it fits itself into the scheme of things… We find the world good to be in because we are adapted to it, and not it to us.

As every era takes its science for the beacon that signals the end of ignorance, Burroughs reflects on how the scientific revelations of his time — a time when we still scoffed at the existence of galaxies beyond our own, had no knowledge of DNA or tectonic plates or Pluto, and considered ourselves the only conscious animal — are breaking apart the old edicts of religion to release a deeper and truer spirituality within:

[…]

Two generations after the young Emerson delivered his rousing Harvard Divinity School address about nature and its echo in human nature as the only true religion, which led Harvard to ban him from campus for thirty years, the elderly Burroughs — a self-anointed “naturist” by creed — writes:

Defining religion as “a spiritual flowering” that can bloom in any bosom, Burroughs writes:

There is no special Providence. Nature sends the rain upon the just and the unjust, upon the sea as upon the land. We are here and find life good because Providence is general and not special.

Men of science do well enough with no other religion than the love of truth, for this is indirectly a love of God. The astronomer, the geologist, the biologist, tracing the footsteps of the Creative Energy throughout the universe — what need has he of any formal, patent-right religion? Were not Darwin, Huxley, Tyndall, and Lyell, and all other seekers and verifiers of natural truth among the most truly religious of men? Any of these men would have gone to hell for the truth — not the truth of creeds and rituals, but the truth as it exists in the councils of the Eternal, and as it is written in the laws of matter and of life.

In a sentiment his twenty-first-century counterpart — the wildlife ecologist and ornithologist J. Drew Latham — would echo in his lyrical reflection on nature as worship, Burroughs adds:

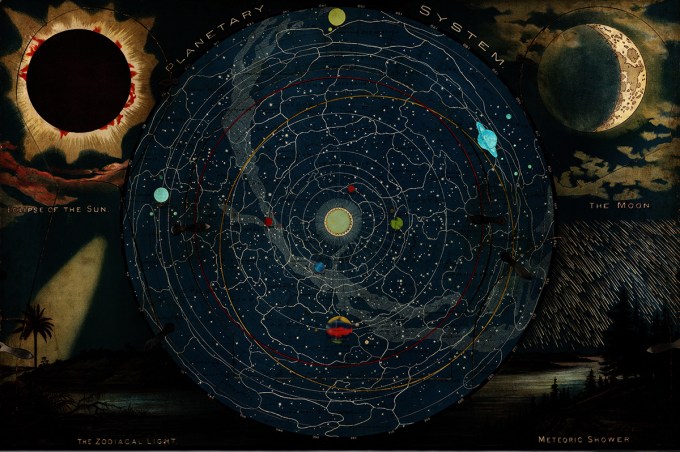

Nearly a century before NASA’s Kepler telescope discovered the first known potentially habitable world in another solar system, Burroughs posits that “innumerable other worlds exist in the abysses of space” and considers our conflicted fallibility, which is both part of our humanity and part of our divinity. Drawing on his lifelong devotion to the consolations of the cosmic perspective, he writes:

Nearly a century before NASA’s Kepler telescope discovered the first known potentially habitable world in another solar system, Burroughs posits that “innumerable other worlds exist in the abysses of space” and considers our conflicted fallibility, which is both part of our humanity and part of our divinity. Drawing on his lifelong devotion to the consolations of the cosmic perspective, he writes:

A man is not saved by the truth of the things he believes, but by the truth of his belief — its sincerity, its harmony with his character… Religion is an emotion, an inspiration, a feeling of the Infinite, and may have its root in any creed or in no creed.

To say that man* is as good as God would to most persons seem like blasphemy; but to say that man is as good as Nature would disturb no one. Man is a part of Nature, or a phase of Nature, and shares in what we call her imperfections. But what is Nature a part of, or a phase of? — and what or who is its author? Is it not true that this earth which is so familiar to us is as good as yonder morning or evening star and made of the same stuff? — just as much in the heavens, just as truly a celestial abode as it is? Venus seems to us like a great jewel in the crown of night or morning. From Venus the earth would seem like a still larger jewel. The heavens seem afar off and free from all stains and impurities of earth; we lift our eyes and our hearts to them as to the face of the Eternal, but our science reveals no body or place there so suitable for human abode and human happiness as this earth. In fact, this planet is the only desirable heaven of which we have any clue.

Echoing Thoreau’s declamation that “every walk is a sort of crusade,” he adds: