Discussion welcome—not just on the history of the role of women in analytic philosophy, or of others whose voices are at risk of being lost, but also on the more general matter of how economic and technological pressures on the institutions that house and curate our research materials affect our understanding of our discipline and shape the work we do, and what we might do in light of those pressures.

She observes: “The habit of ignoring female philosophers has become so entrenched that even the secondary literature is marked by their absence.”

At the Blog of the APA, Sophia Connell (Birkbeck College London) gives us an example to work, writing about the “striking absence of female names” from recent histories of analytic philosophy:

Philosophy, and especially the history of philosophy, is not known for being in a rush. But an appreciation of the factors that go into shaping our discipline and its self-understanding might give us a sense of urgency.

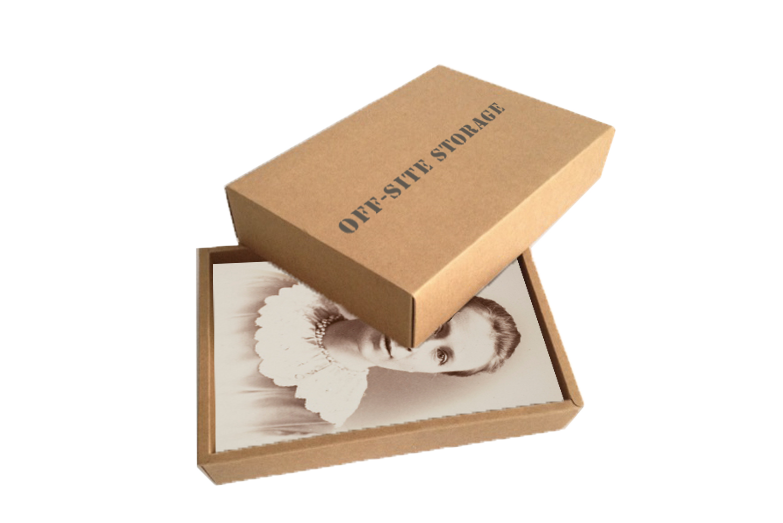

Libraries purge their shelves of hard copies of old journals and of books long out of print—such as Sophie Bryant’s masterpiece, On Educational Ends (1887), Susan Stebbing’s Introduction to Logic (1930), and Alice Ambrose’s Essays in Analysis (1966)—to make way for new books, some of which are histories of philosophy that leave out any mention of women. The work of female philosophers further disappears as digitized materials emphasise only those whose writings supposedly shaped our discipline. Think of the efforts spent on chronicling everything that Bertrand Russell ever wrote, including all of his letters, or on collecting and cataloguing Wittgenstein’s writing. Meanwhile, Sophie Bryant’s papers languish in boxes in a private day school for the daughters of the wealthy middle class.

Familiar histories of 20th century analytic philosophy center on exclusively male figures. This narrative makes it seem like female philosophers played no significant role in the modern development of analytic philosophy. This is in part due to laziness in citation; when considering an argument or concept, philosophers often reach for the person they think most representative.

For example, the important 2008 book What is Analytic Philosophy by Hans-Johann Glock does not discuss any female philosophers. The extensive bibliography contains only one work by a female philosopher of the early analytic period, a short paper by Susan Stebbing. In 1933, Stebbing became the first female Professor of Philosophy in the United Kingdom; she wrote numerous important articles and nine books. Stebbing was also instrumental in introducing ideas from the Continent, particularly logical positivism, to UK philosophers. Her centrality to the philosophy of this period is not conveyed in Glock’s book, which reinforces her relative obscurity; many students of analytic philosophy have never heard of her or read her writing.

Certain contemporary developments, such as pressures on libraries to cull their collections of hard copies and the academy’s increasing reliance on digitized materials, contribute to the worry of forgetting some valuable voices in the history of our discipline:

The longer the exclusion goes on, the harder it is to undo.:

Despite being educated and then publishing in the same venues as their male counterparts, female philosophers were and continue to be much less cited and discussed than male philosophers—the discussion, discourse, and processes of philosophy gradually purge their voices. Their published work is fading away because they are not in our courses and nobody reads and tries to understand them. The further away we get, the harder it is to understand these writings; they are not familiar and thus they may seem irrelevant.

Given the exclusion of women, they usually think of a man. A case in point: thick concepts, or the idea that some words are both descriptive and evaluative, are almost always attributed to Bernard Williams. But they were in the air in Oxford in the 1940s as a collective response to Ayer’s emotivism. A lively discussion of this topic occurred in Oxford sometime in the late 1940s involving Midgley, Murdoch, and Anscombe. As Midgley tells it in her autobiography The Owl of Minerva, “we were discussing the meaning of rudeness. I think this topic must have come up out of background discussions that Philippa Foot finally expressed in her splendid article called ‘Moral Arguments’ (which appeared in Mind, Vol. 67, 1958), where she used the example of ‘rudeness’ to show that a word’s descriptive and evaluative meanings are not separate and independent” (115). It takes women writing about women to bring women to light in this history.

The absence of women from analytic philosophy’s history ends up being self-reinforcing: