Days go by and he does not return.

One day a lady had gone into the woods

just a little way. But when she came out

she spoke in words that none of the other people

could understand.

And she was never herself again.

But the people who had gone only to the edge of the woods

had heard the golden birds

and had been happier for hearing their song.

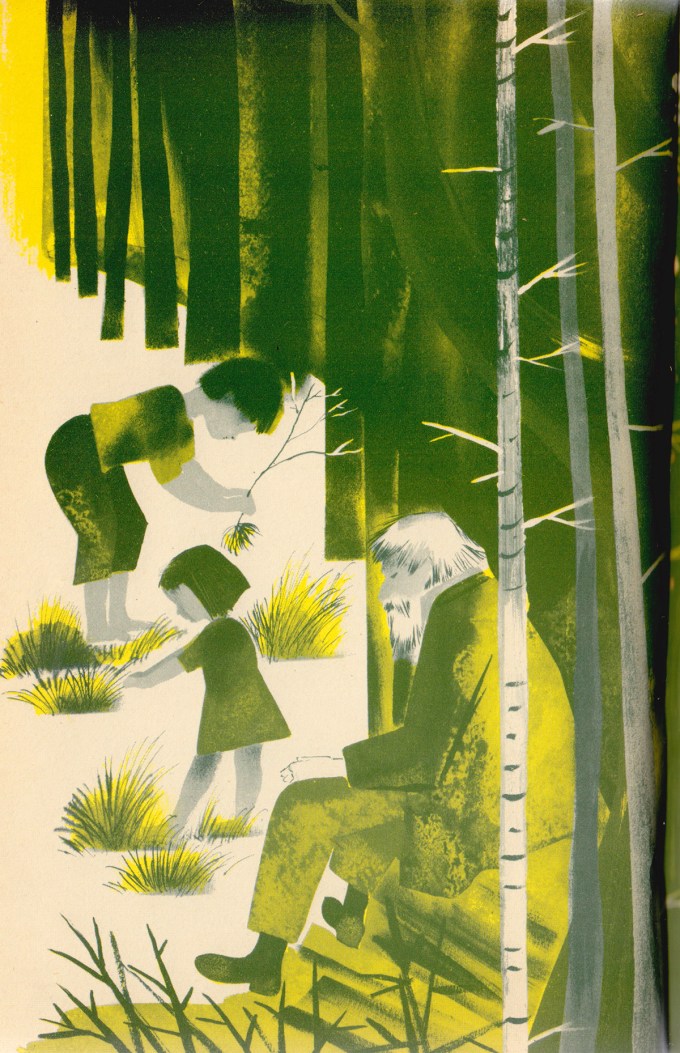

As the boy weeded the asparagus

there were times when he sang as he worked.

Sometimes his song was happy

as the birds in the air.

Sometimes his song was sad

like a spring mist in the night;

or like the depths of a lake at noon, very quiet.

But always the songs he sang were such

that the people who came to buy in the afternoon

stayed to listen

and then had to hurry home to their suppers before dark.

And as they walked along the paths to their homes

the winds seemed softer

and the evening star seemed brighter

for their having listened to the boy’s song.

Then, just before dawn, a voice comes from the wood, “clear and more golden than the song of the golden birds.” The little girl hears it in her sleep, and smiles; listening at his window, the old man “remembers all he had forgotten and knew more than he had ever known before.” So it is that Margaret Wise Brown contours the outlines of the transformation, but she lets the reader fill it in with their own meaning, for it is a transcendent experience she writes of, and half a century before her William James had qualified ineffability as one of the four features of transcendent experiences.

But even he is too afraid of the song to go into the woods looking for its source.

At night when I hear them singing far off,

I remember strange and quiet things,

the way the wind bends the grasses

as it blows across the field.

I hear the sound of the rain,

I remember the warm sunlight and the long evening shadows.

I think of the grey night and of the vast sea

and I remember all I have forgotten

that ever made me happy or sad.

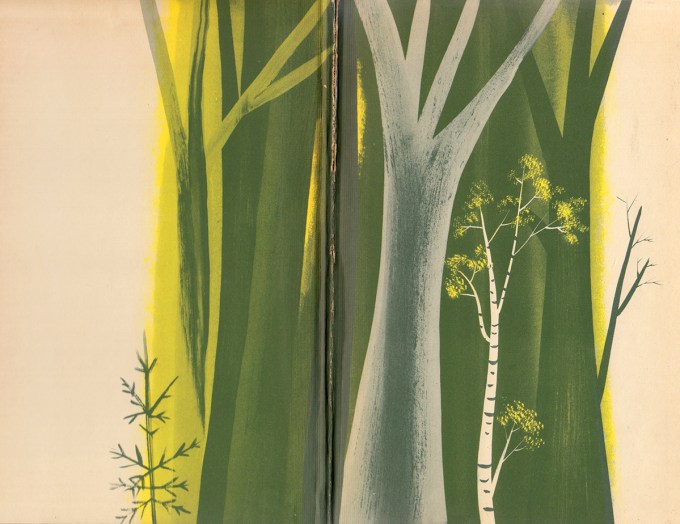

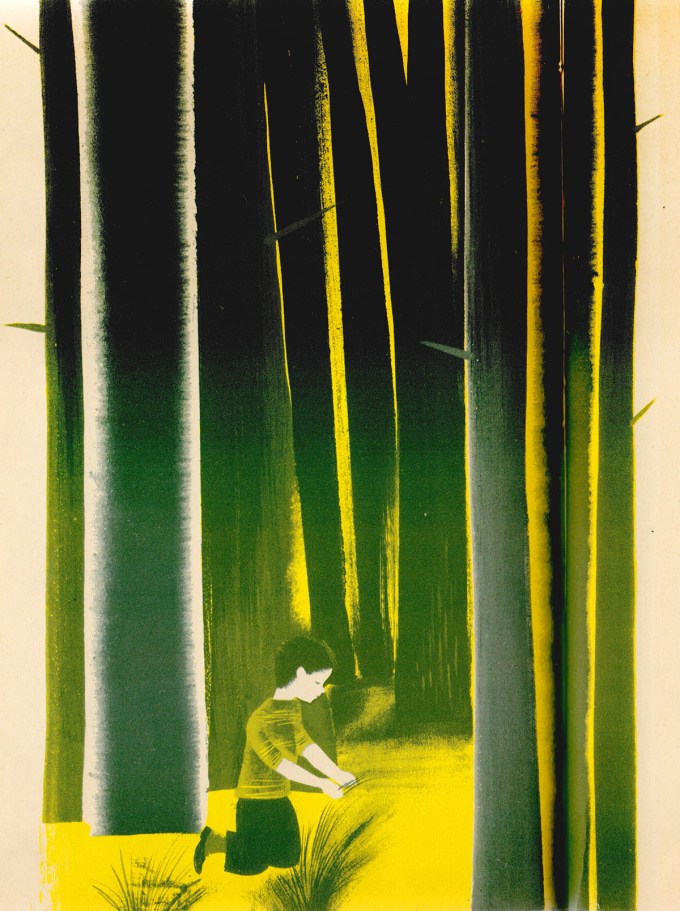

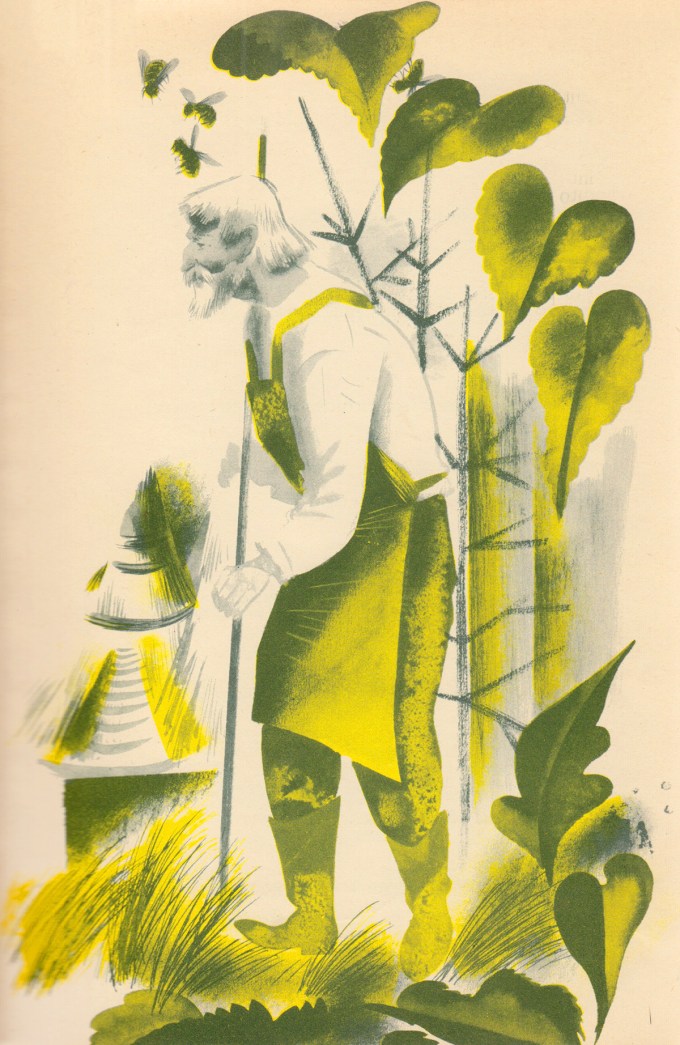

The people who flock to his house for honey and asparagus never dare venture past the edge of “the wood of the golden birds,” believing it to be a magic wood — “the unknown from which there is no return”; of the few brave souls who have wandered in, none ever returned. The old man himself never goes into the dark wood, but sometimes — at night, or early in the morning — he can hear the golden birds sing.

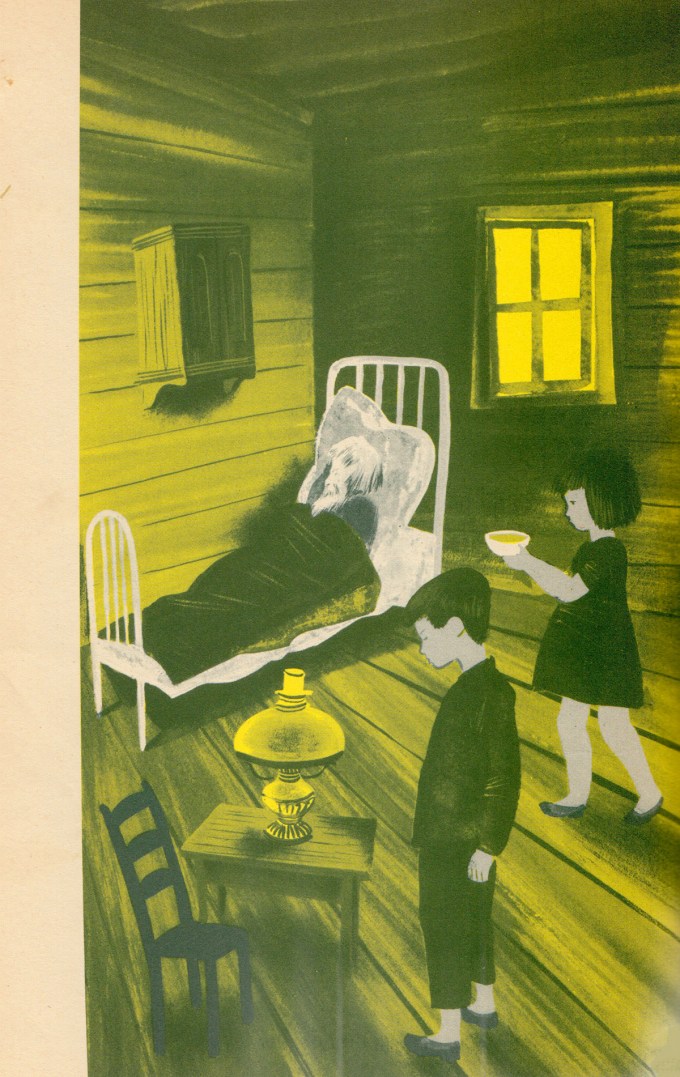

Day by day, the children grow more and more worried about the old man, until they decide that only one thing could revive him.

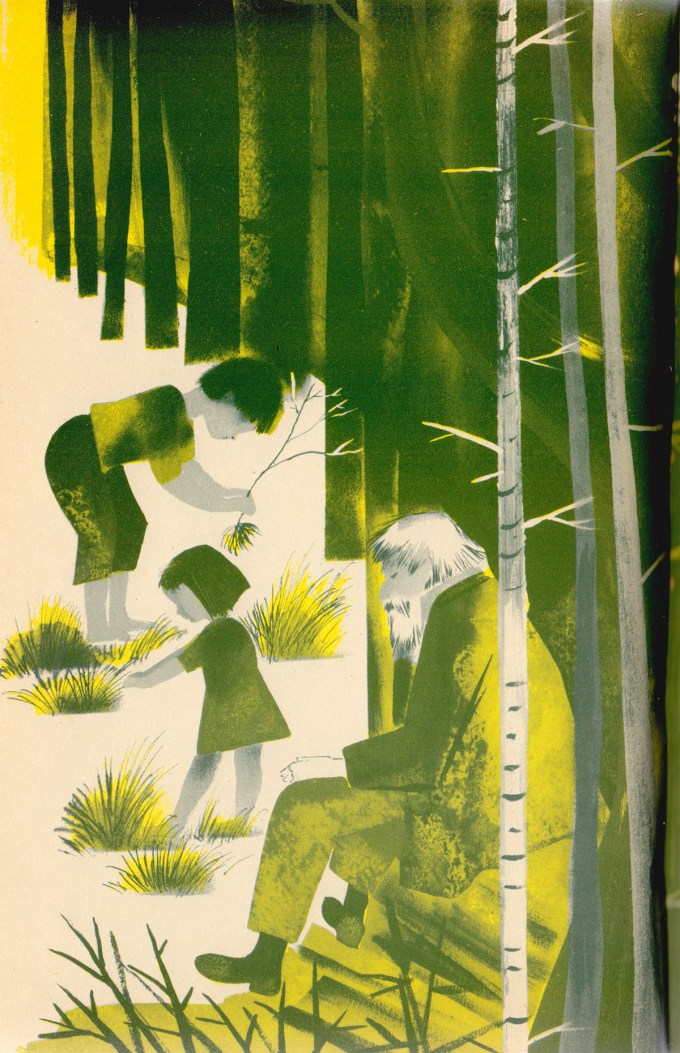

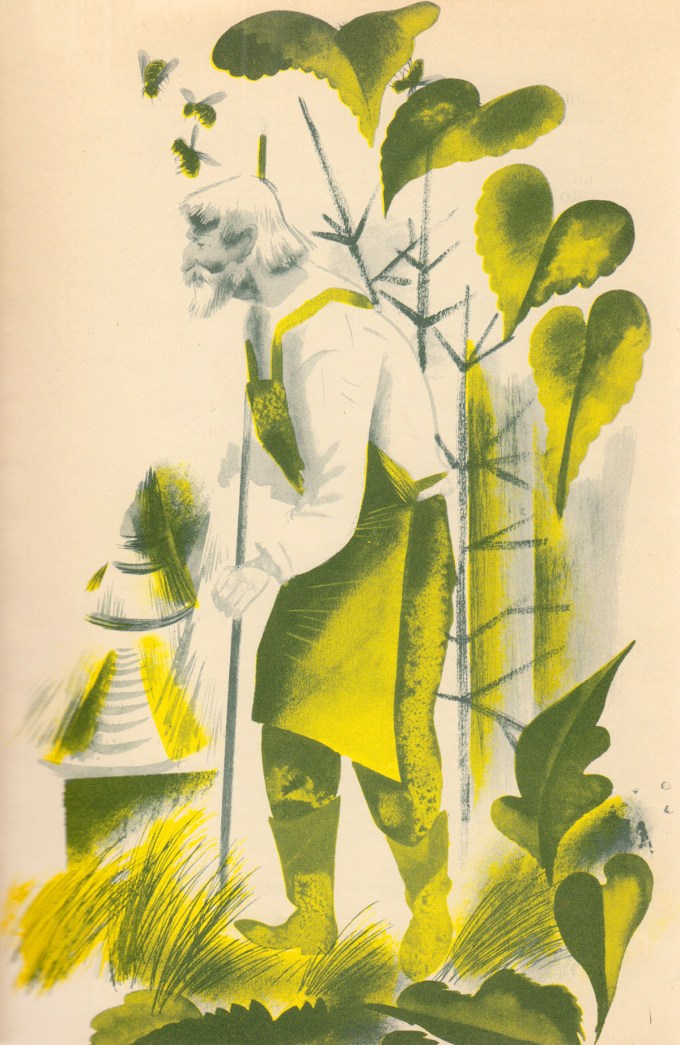

This magic forest grows behind the house of “an old man with white hair and green eyes,” who is “never a year older or a day younger,” and who keeps honeybees and grows asparagus for a living.

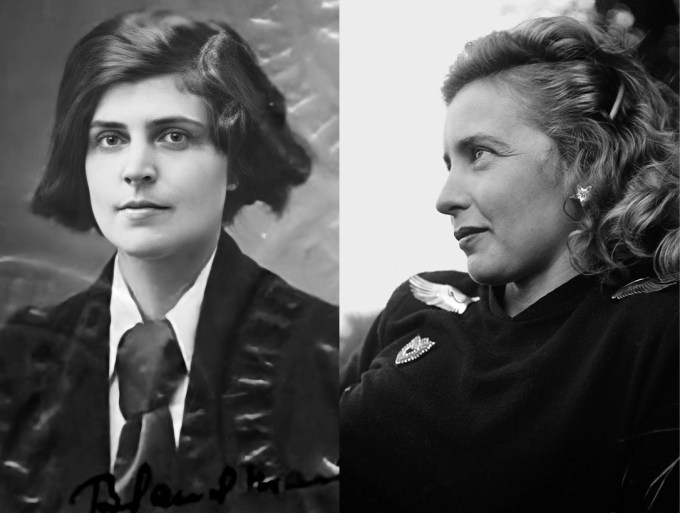

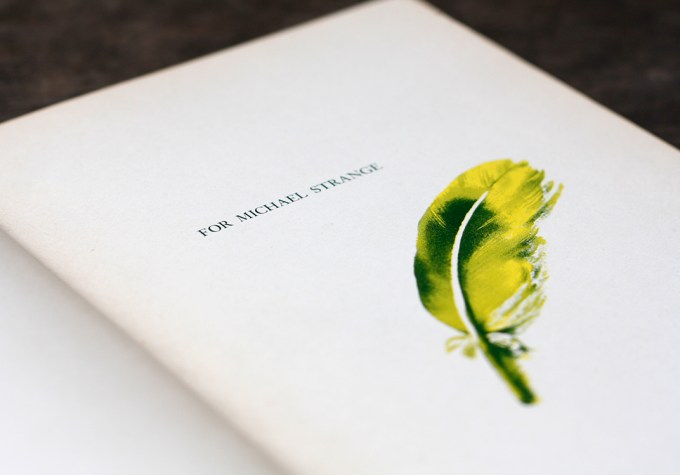

Michael Strange lived through that summer before entering the dark wood in the last weeks of autumn never to return, remaining, as every great love does, imprinted on the song of Margaret Wise Brown’s life.

He had returned with a golden feather piercing his heart and the secret knowledge of the dark wood — the knowledge of life in its totality, ravishing and savage — a magic forest in which darkness and light are forever aflicker in a single enchantment.

The children find happiness working in the old man’s garden, but as time unspools, they grow more and more curious about the dark wood of the golden birds. The bees, they reason, go into the magic forest every day and not only return, but return with wildflower nectar for honey that “makes the sick people well and the sad people happy,” “the slow people fast and the noisy people quiet.” There seems to be a secret magical vitality in the dark wood, but none of its enchantments beckon the children more powerfully than the song of its golden birds.

It happened in the woods

a long time ago.

In the dark woods

where the golden birds

sang all through the night

and the day.

While she was writing the book, Margaret Wise Brown was watching her beloved flicker in and out of consciousness. She must have wondered about the mystery of it all, about the harrowing unreality into which Michael vanished when she slipped into a coma her doctors at first took for permanent death.

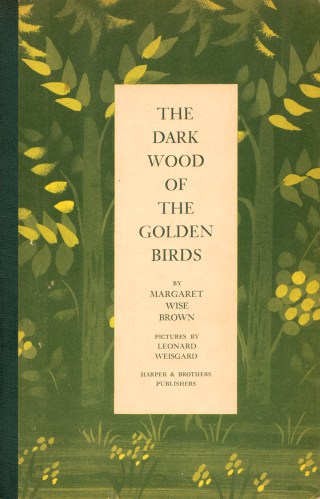

On the last day of spring in 1950, three years after Goodnight Moon had enraptured the world with its bright playfulness, The Dark Wood of the Golden Birds (public library) appeared, somber and numinous with its elegiac prose, and its haunting duotone of otherworldly greens and yellows, and its the simple dedication: “For Michael Strange.”

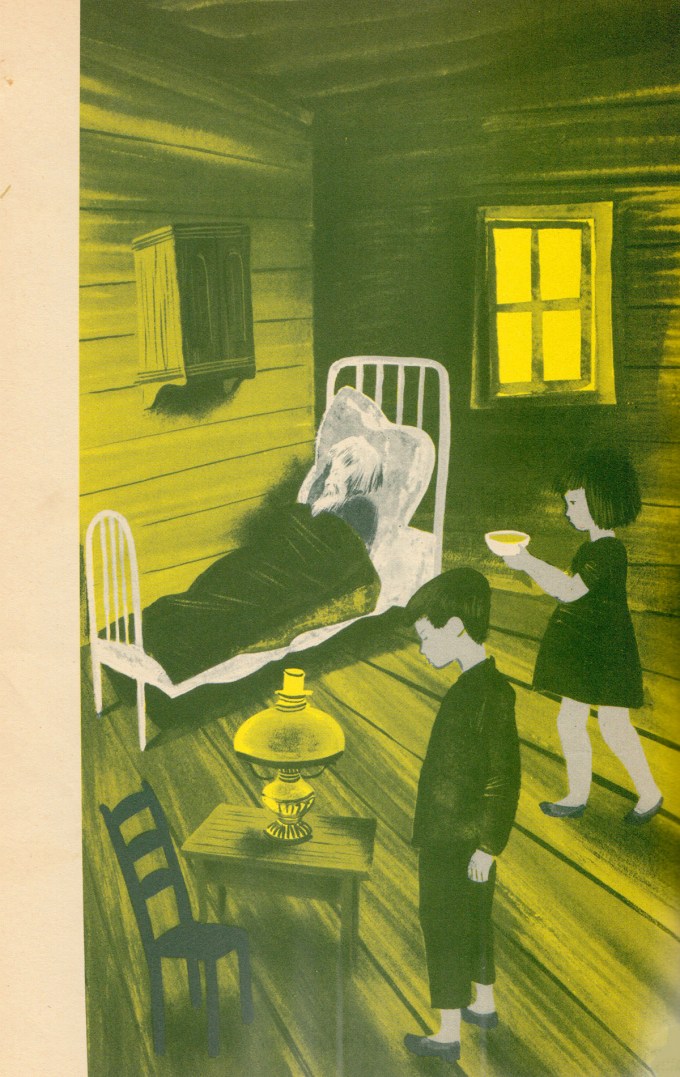

Then came the time of the great silence.

No winds blew

and even the bees seemed to stop their buzzing.

The sun was warm on the earth.

The old man slept

and all the little girl could hear

was the sound of her broom

as she swept the house.

There had never been such a quiet day before.

It was the quietest day in the world.

When the children plead with the old man to condone their venture into the woods, he only reminds him that it is not to be done, for no one has ever returned. When they ask what lies beyond the dark wood, for there is surely an other side, he simply tells them that “on the other side of the dark wood is the land that no one knows.” When they press on with their restive curiosity, he grows angry, then falls silent, falls ill.

Illustrated by Brown’s longtime collaborator and friend Leonard Weisgard, and written with her singular poetics, the story begins:

Margaret Wise Brown (May 23, 1910–November 13, 1952) never did anything half-heartedly. When the love of her life fell mortally ill, she did the hardest thing in life — facing the death of a beloved while remaining a pillar for their passage — the best way she knew how: she wrote her a love letter in the form of a children’s book.

His sister busies herself in the garden to keep the tears of loneliness and anticipatory loss from coming.

If only he could hear once more

the song of the golden birds…

Then he would remember all he has forgotten…

He would remember the sky and the sunlight on the grass.

He would remember the kindness in people’s hearts

and the sweet drowsy humming of the season of the bees.

In the decades since, the book has fallen out of print in a culture that has no room and no language for grief, and no tolerance for the darkest dimensions of life, which crack open our vastest capacity for light. It would take an act of countercultural courage and resistance for a modern publisher to bring this work of uncommon beauty and tenderness back into the fold of life.

In a passage revealing Margaret Wise Brown as one of the great unsung poets of the twentieth century, sonorous with her secret devotion to poetry, the boy tells his sister:

The next day when the sun shone

on the house in the field of grass

it woke up the bees and the old man

and the little girl.

And it woke up the boy

who was once more asleep in his own bed.

One day, a brother and a sister whose parents have died wander to the old man’s house.

In a gentle nod to The Quiet Noisy Book, which she had published earlier that year, also illustrated by Leonard Weisgard, Brown writes:

The old man was sorry for them;

and when he heard their happy laughter

and saw how they ran with the bees from flower to flower

he loved them.

And he took them to live with him

and gave them a home.

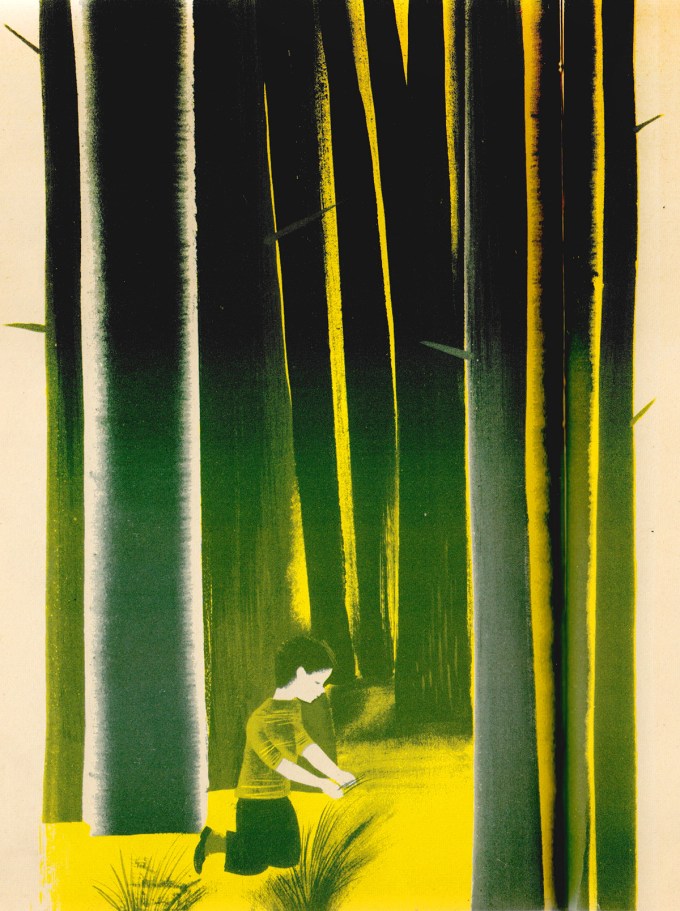

And so, the boy decides that he must bring the song of the golden birds to the old man. One morning, “without telling anyone goodby,” he leaves the house and heads for the woods.

The night came on

more softly than ever

with shooting stars

and no winds blowing.

There were no colors now,

everything was dark in the night,

and the night was black

and heavy and silent.

And in their song he heard all that was beautiful to hear,

the ringing of bells

and the soughing of the wind;

he heard the echo that is hidden in a sea shell,

the deep sea music;

he heard laughter and singing

and the songs his mother sang to him long ago.