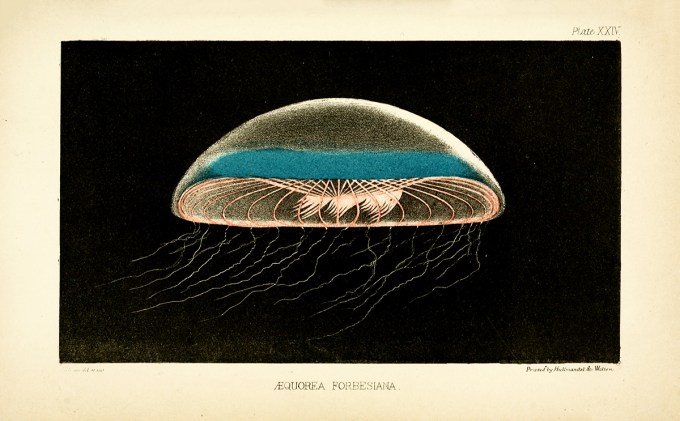

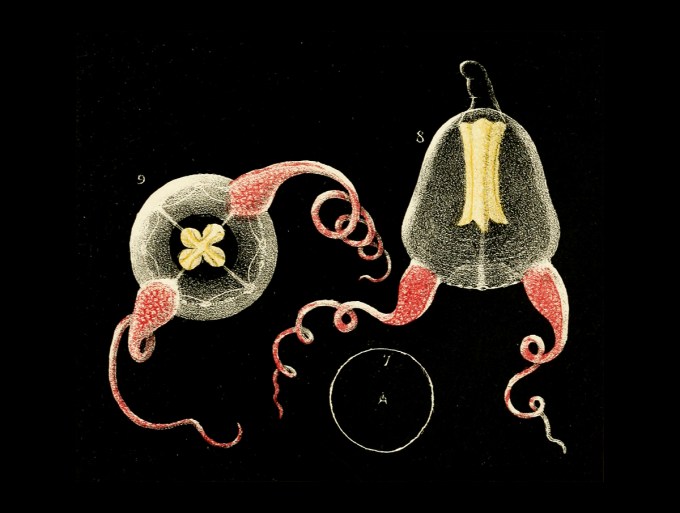

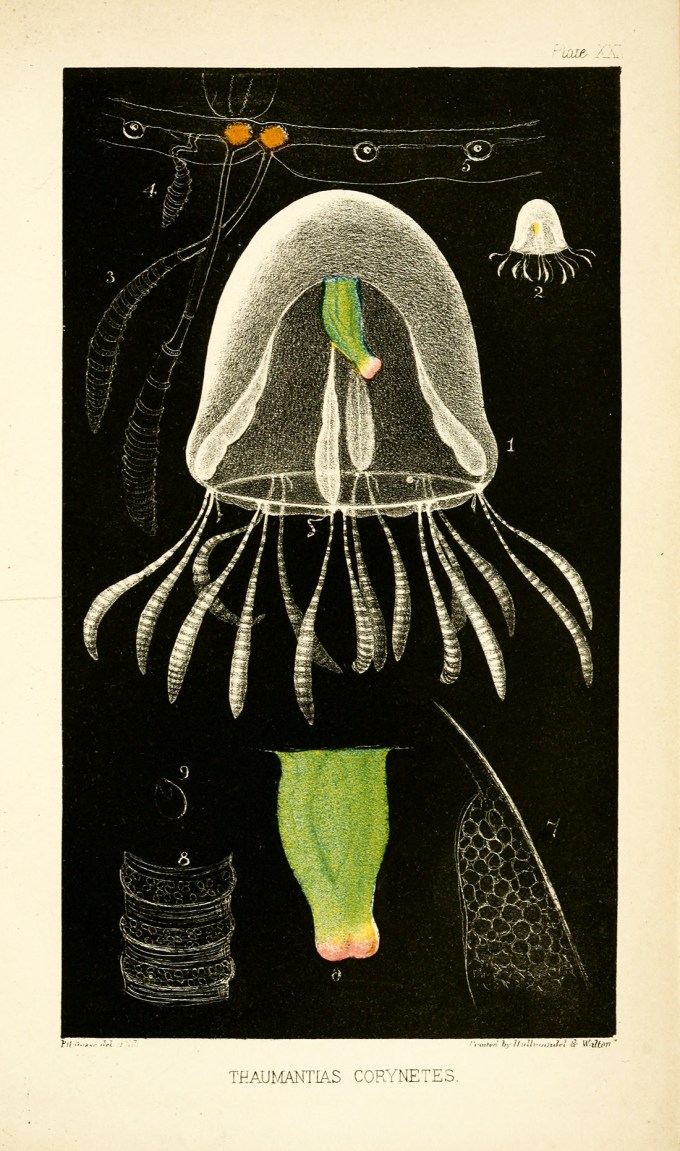

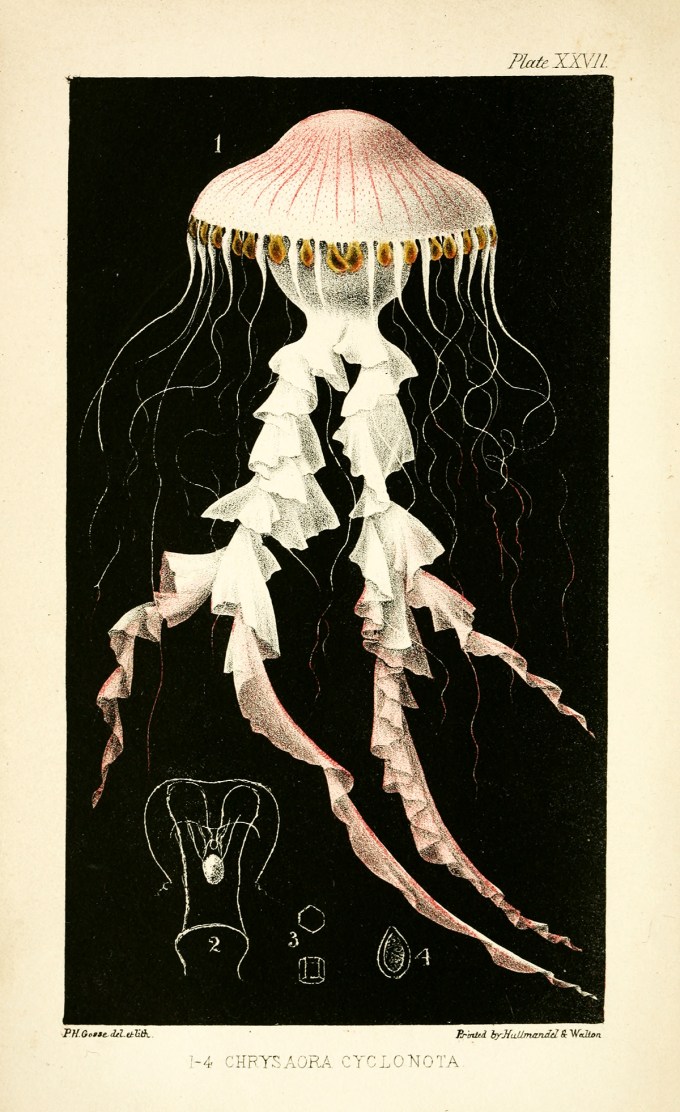

Each of the animals he describes — the mollusk and the medusa, the shrimp and the sea lemon, the dinoflagellate and the dead man’s fingers coral — he describes with absolute reverence for its beauty and microscopic magnificence, all the more enchanting for being so overlooked.

“Contemplating the teeming life of the shore, we have an uneasy sense of the communication of some universal truth that lies just beyond our grasp,” the poetic marine biologist Rachel Carson wrote with her mind perched on the water’s edge, contemplating the ocean and the meaning of life in an era when the boundary between land and water marked the shoreline between knowledge and mystery, between the mapped terrestrial world and a world still more mysterious than the Moon.

Although, throughout his life, Gosse struggled to reconcile science and religion, through this portal of creaturely awe he touched the elemental truth to which his culturally conditioned mind blinded him — the unbroken link between these exquisite primitive creatures and ourselves. Six years before Darwin exposed the science beneath the kinship of life-forms in On the Origin of Species and a century before Lucille Clifton celebrated the poetics of “the bond of live things everywhere,” Gosse exulted:

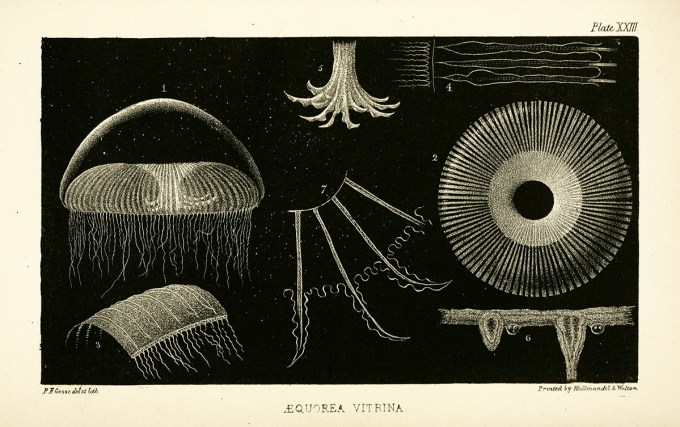

Complement with Gosse’s compatriot William Saville Kent’s kaleidoscopic illustrations from the world’s first pictorial glimpse of the Great Barrier Reef and the living wonders rendered in Cephalopod Atlas — the world’s first encyclopedia of deep-sea creatures, drawn from the epoch-making Valdiva expedition and published a decade after Gosse’s death, upending the longtime belief that the ocean is lifeless below 300 fathoms: a testament to the frequency with which every time we have let our self-referential imagination limit the complexity, diversity, and resilience of life, we have limited the wonder of possibility and we have been wrong.

The following pages I have endeavoured, as far as possible, to make a mirror of the thoughts and feelings that have occupied my own mind during a nine months’ residence on the charming shores of North and South Devon. There I have been pursuing an occupation which always possesses for me new delight, — the study of the curious forms, and still more curious instincts, of animated beings… Having conveyed pleasure and interest to myself, I thought might entertain and please my reader.

Gosse made what he made — his visual art and the art of understanding we call science — in the spirit in which all genuine creators make what they make:

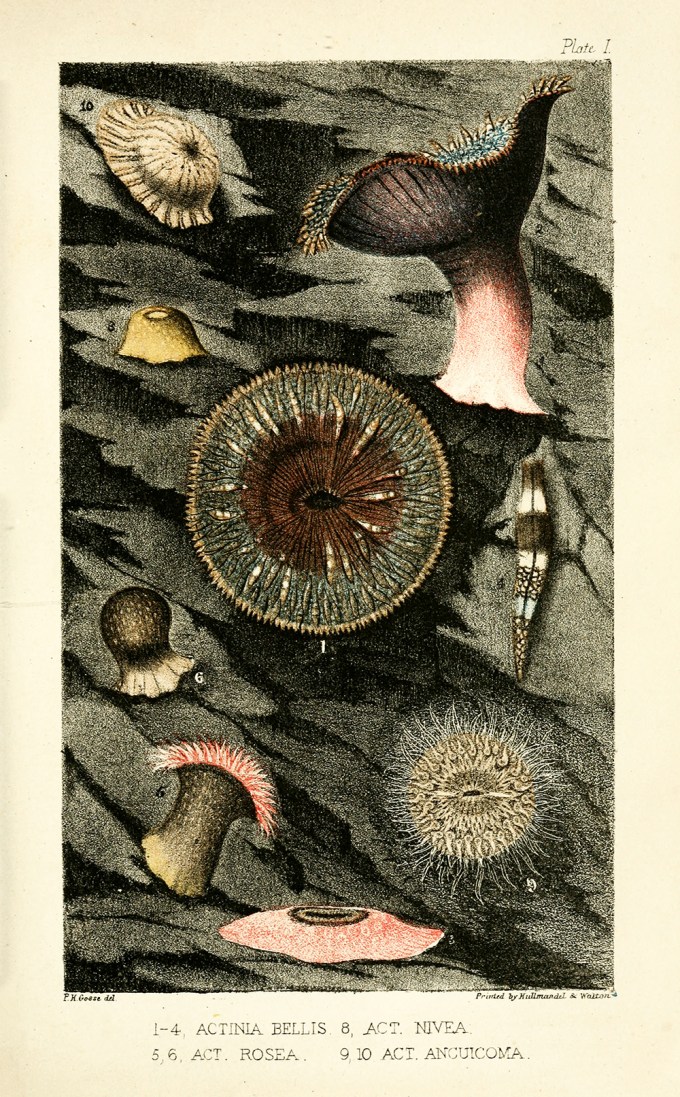

In this poetic spirit, leaning on Wordsworth’s timeless pronouncement that “Poetry is the breath and finer spirit of all knowledge [and] the impassioned expression which is in the countenance of all Science,” Gosse plunges into raptures about particularly dazzling facets of these overlooked animals, many of them wholly novel to human eyes. He kneels on the rocks to peer into the “exceedingly charming” “natural vivarium” of the tide pool with its colorful underwater forest of seaweed, exults in discovering the valved mechanics of how Pecten opercularis — the queen scallop — climbs and leaps with its “delicate little foot,” marvels at its frilly microscopic gills, delights in its diamond eyes, “possessing all the brilliancy of precious stones.”

That the increase of knowledge is in itself a pleasure to a healthy mind is surely true; but is there not in our hearts a chord that thrills in response to the beautiful, the joyous, the perfect, in Nature?

Urging the reader not to expect “a book of systematic zoology; nor a book of mere zoology of any sort,” Gosse instead offers an invitation to contemplative companionship in lively curiosity about and amid the living world:

I ask you to listen with me to the carol of the lark, and the hum of the wild bee; I ask you to stand with me at the edge of the precipice and mark the glories of the setting sun; to watch with me the mantling tide as it rolls inward, and roars among the hollow caves; I ask you to share with me the delightful emotions which the contemplation of unbounded beauty and beneficence ever calls up in the cultivated mind.

These objects are, it is true, among the humblest of creatures that are endowed with organic life. They stand at the very confines, so to speak, of the vital world, at the lowest step of the animate ladder that reaches up to Man; aye, and beyond him… Here we catch the first kindling of that spark, which glows into so noble a flame in the Aristotles, the Newtons, and the Miltons of our heaven-gazing race.

Published the year Gosse created and populated the world’s first pubic aquarium at the London Zoo — a decade after Anna Atkins walked those selfsame shores to collect the seaweed she rendered in stunning cyanotypes that made her the first person to illustrate a book with photographic images, a decade before the young German marine biologist Ernst Haeckel coined the term ecology and left Darwin wonder-smitten with his exquisite paintings of jellyfish, and exactly 100 years after Carl Linnaeus created the modern nomenclature of nature — Gosse’s lyrical guide to the life of the shore features twenty-eight exquisitely painted plates of marine creatures, labeled with their Linnaean names, “all drawn from living nature, with the greatest attention to accuracy,” comprising “about two hundred and forty figures of animals and their component parts, in many instances drawn with the aid of the microscope.”

To the then-common, still-common, unconsidered objection that to bridge science and beauty is “to degrade science below its proper dignity,” Gosse counter-objects with a sentiment of lyrical lucidity:

A century earlier, the poetic English marine biologist and naturalist Philip Henry Gosse (April 6, 1810‐August 23, 1888), inventor of the seawater aquarium, extended a tender and trailblazing invitation into the wonders of the water world in his 1853 treasure A Naturalist’s Rambles on the Devonshire Coast (public library | public domain) — an uncommon marriage of scientific investigation and poetic presence.