She was thirty.

But before any portal of opportunity had opened, she too fell ill. At nineteen, Virginia was diagnosed with tuberculosis — the infectious disease that killed one of every seven humans born between the dawn of our species and the dawn of the century in which Virginia was conceived, the crescendo of the epidemic aptly called consumption for the slow, unrelenting way in which it syphons the vitality of its victims.

Two weeks after her death, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle — which had given the young Whitman his literary start nearly a century earlier, and which remained attentive to marginalized artists of uncommon talent — elegized plainly: “Her work was a delight to children and their elders, and it will be missed.”

Virginia Frances Sterrett died on June 8, 1931, of tuberculosis — a disease without cure until the development of the antibiotic streptomycin fifteen years later.

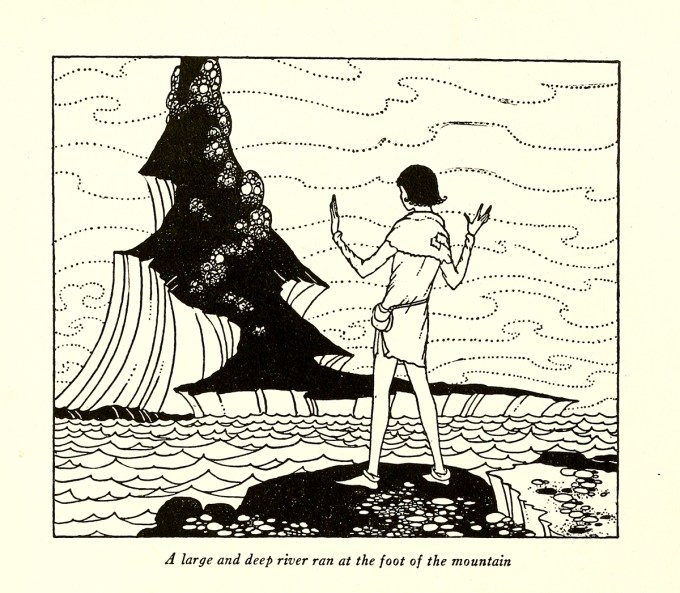

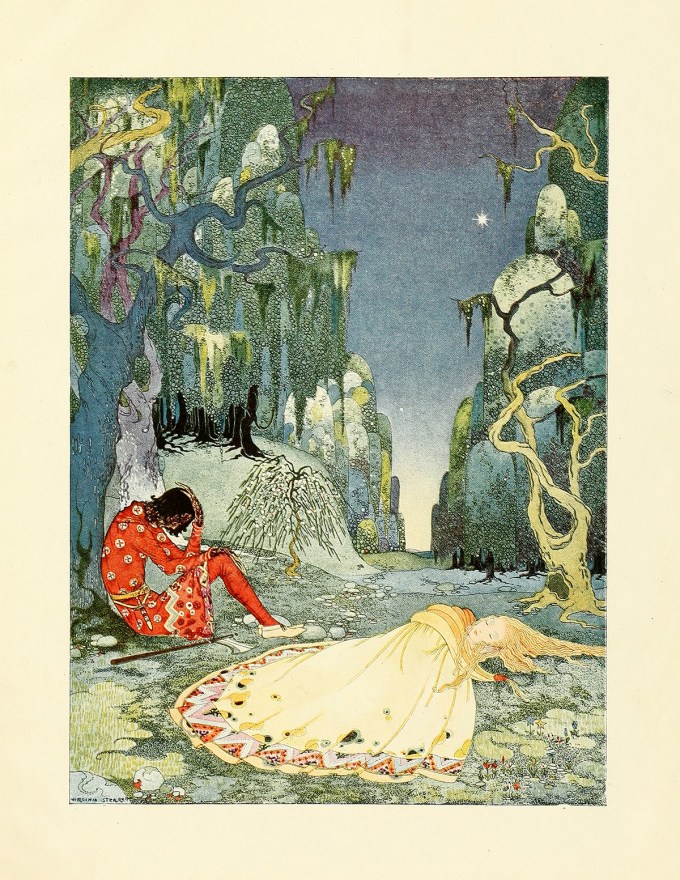

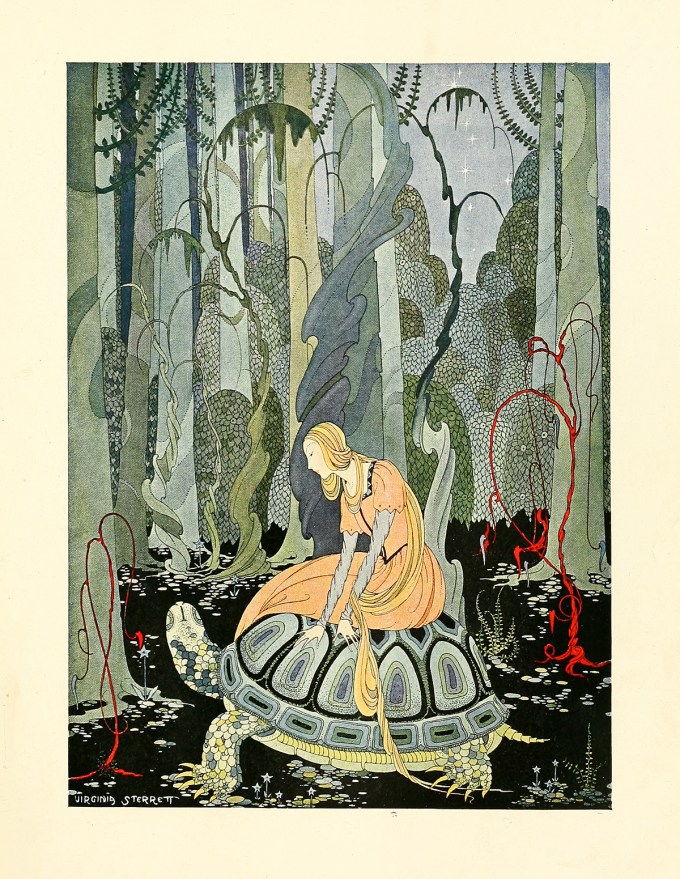

But despite fourteen months at the sanatorium — the same amount of time she had spent in art school — Virginia’s health continued to deteriorate. Hoping that a brighter, warmer climate might improve it, the small clan of women moved to Southern California and made a modest home in a bungalow covered with roses in the foothills of the San Gabriel Mountains, where Virginia kept working on her Arabian Night drawings.

The unexpected assurance opened up that subtle valve of self-permission that allows a gifted young person to consider — against the tide of their cultural and biological inheritance — the possibility of making a life in art.

She dropped out of school and took a series of jobs at various Chicago advertising agencies, earning a week and grateful to earn it, but finding the work — endless drawings of pots, pans, beds, and travel bags — soul-syphoning.

Then, once again, a friend — another silent champion with more passionate confidence in Virginia’s talent than she herself had — took some of her drawings to Chicago’s annual book fair.

Imagine how it must have buoyed her bedridden spirits to receive a letter from a large Philadelphia publishing company nearly a year after one of their representatives had fallen under the spell of her drawings at the Chicago book fair.

Thrilled by the landscape paintings of the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century French masters, Virginia dreamt of traveling to Europe to continue her interrupted art education. But France remained a landscape of the imagination, visited only on the drawing table of her fairy-tale illustrations.

A journalist for the local paper visited the young artist in her bungalow was impressed to find this teenage girl, born in the first year of what has been called “The Century of the Self,” full of “gracious simplicity of manner and a sweet modesty that seemed quite amazing in this day of sophistication and self-centeredness.” (What the journalist would have made of our present Century of the Selfie is a self-evident tragicomedy, the only appropriate calibration of which is James Baldwin’s timeless remark about Shakespeare’s time.)

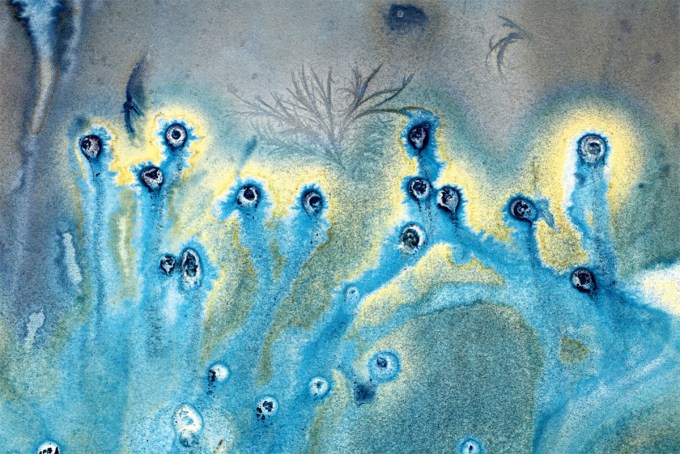

A century hence, Virginia Frances Sterrett’s art continues to haunt with its delicate delight and its solemn tenderness, continues to cast its enchantment, continues to rise from page and screen as an inviting escape ladder into a lovelier world available to the imagination of any person in any reality.

Within a year, she won a stipend to the Art Institute of Chicago — one of the country’s oldest, most esteemed and egalitarian art schools — and moved back to her hometown, which the family had left for Missouri, then Kansas, searching for livelihood after the father’s death when Virginia was still a toddler.

That achievement, the anonymous and admiring journalist wrote, was “beauty, a delicate, fantastic beauty, created with brush and pencil… pictures of haunting loveliness.”

Virginia Frances Sterrett (1900–1931) had barely learned to walk when she began drawing. She never stopped, and her talent never ceased winning over its legion of silent champions.

At fourteen, unthoughtful of achievement and ambition, friends persuaded her to send her drawings to the Kansas State Fair. To her surprise, she won first prize in three different categories. The originality of her drawings — which, throughout her life, came to her as visions she felt she was merely channeling onto the page with her pen and brush — captivated two successful local artists, who encouraged her to pursue formal study.

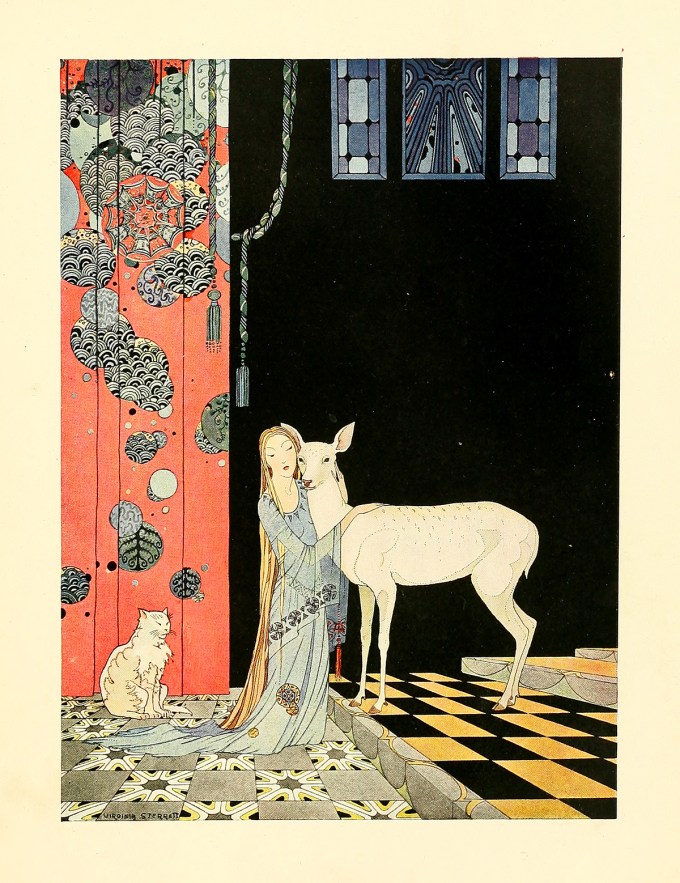

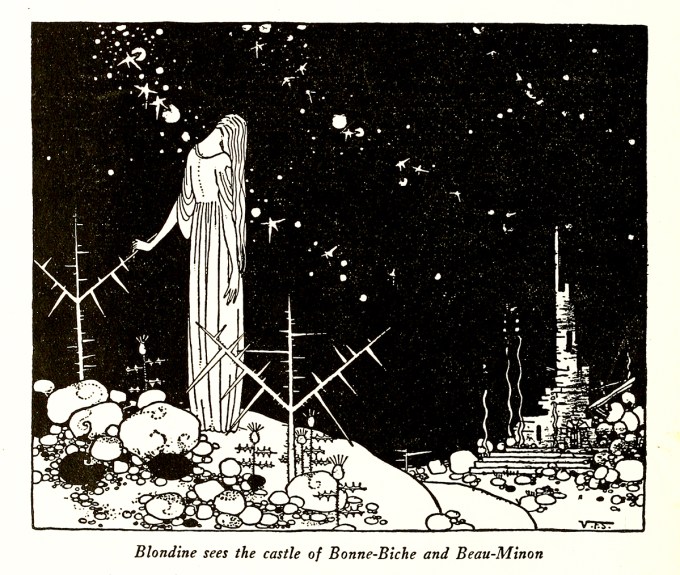

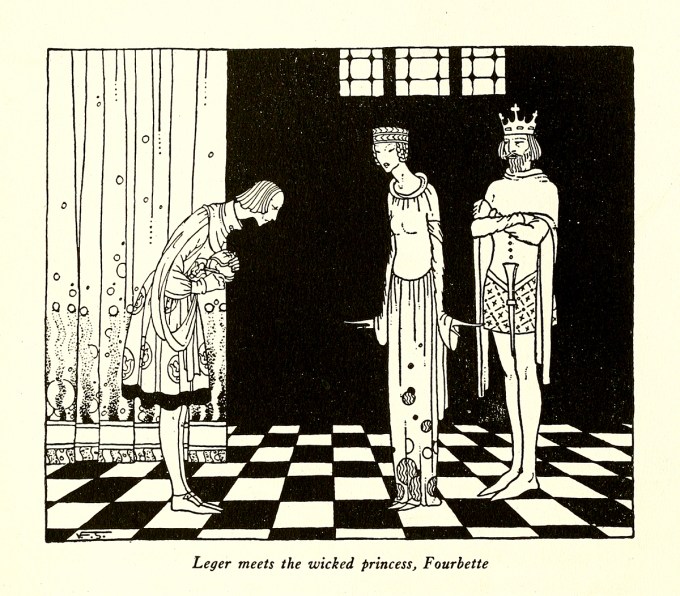

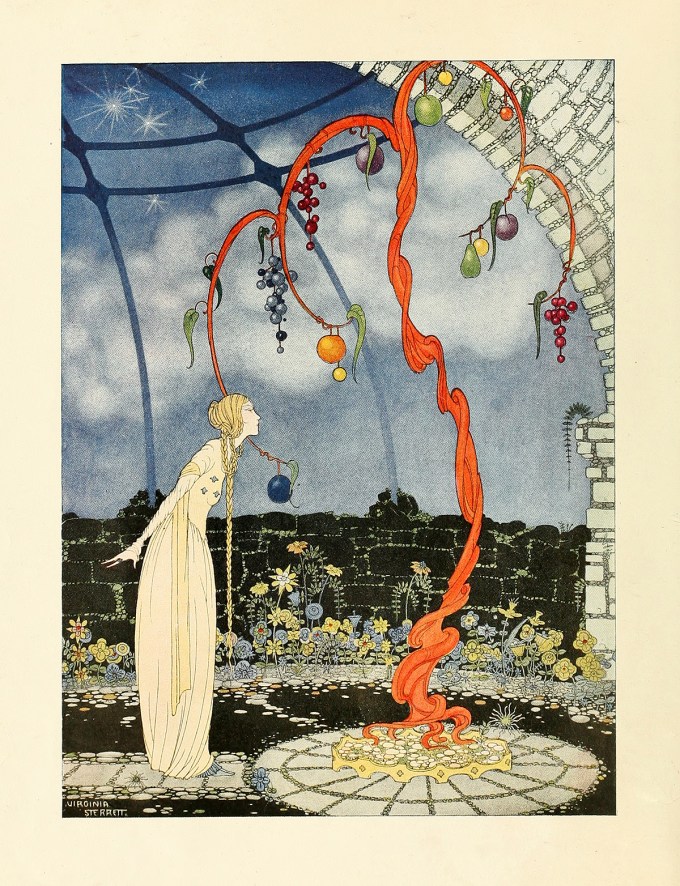

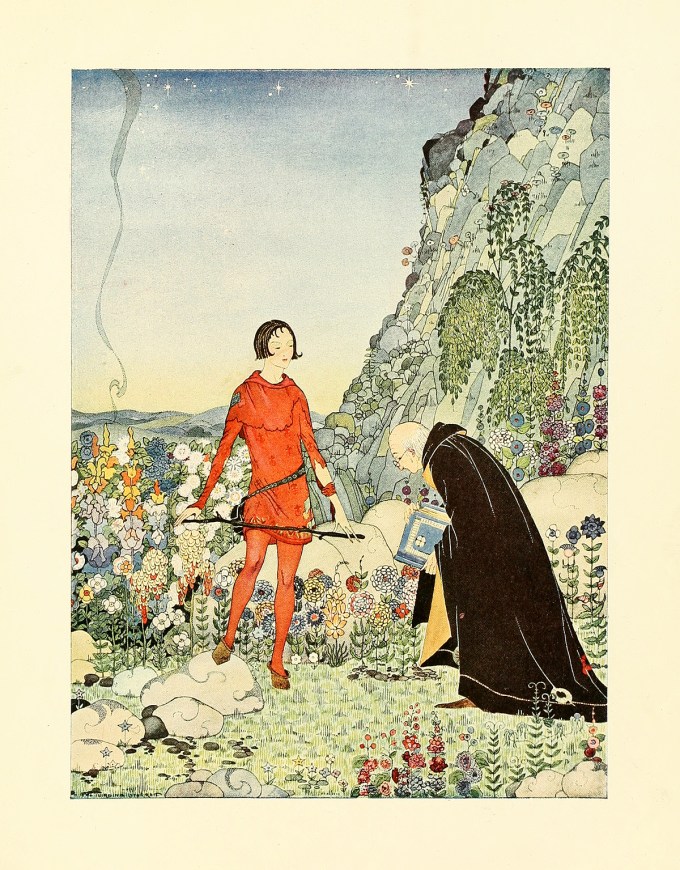

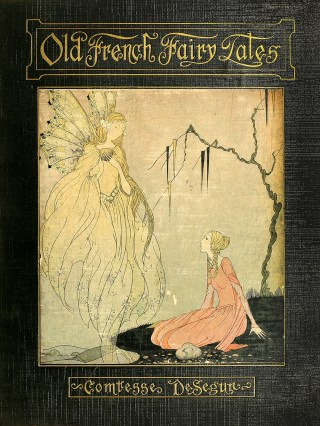

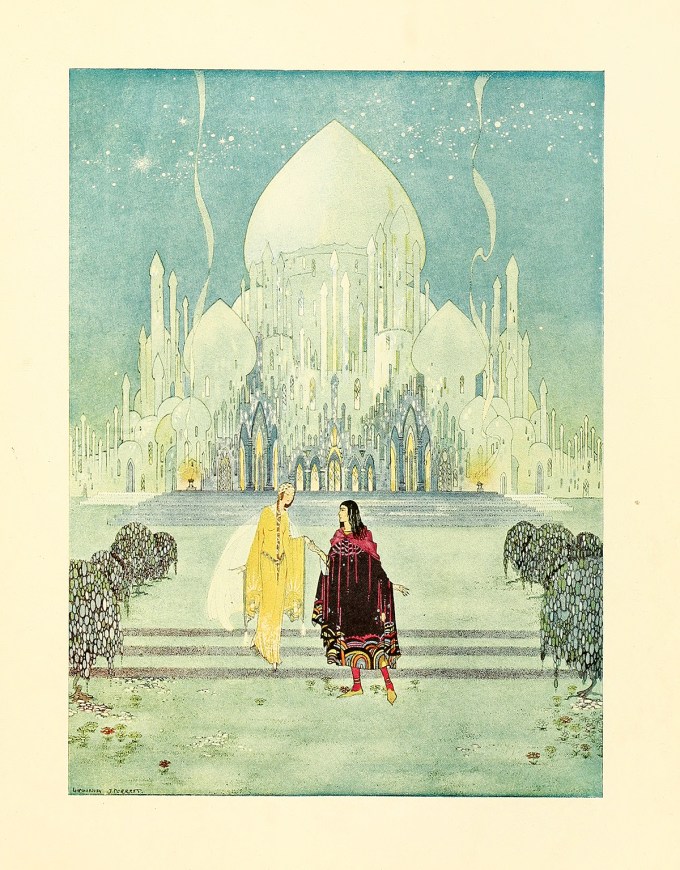

So it is that Virginia Frances Sterrett — nineteen, bedridden, impecunious — was commissioned to illustrate an American edition of Old French Fairy Tales (public library | public domain) by the nineteenth-century Russian-French writer Sophie Rostopchine, Countess of Ségur, who began her literary career in the lap of privilege when she was nearly sixty.

Her talent enchanted the local community. Word of her fairy-tale illustrations got around. She created a series of stage set drawings for the Hollywood Community Theater’s production of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. An established local artist and art educator ten years her senior organized an exhibition of Virginia’s drawings at her studio gallery.

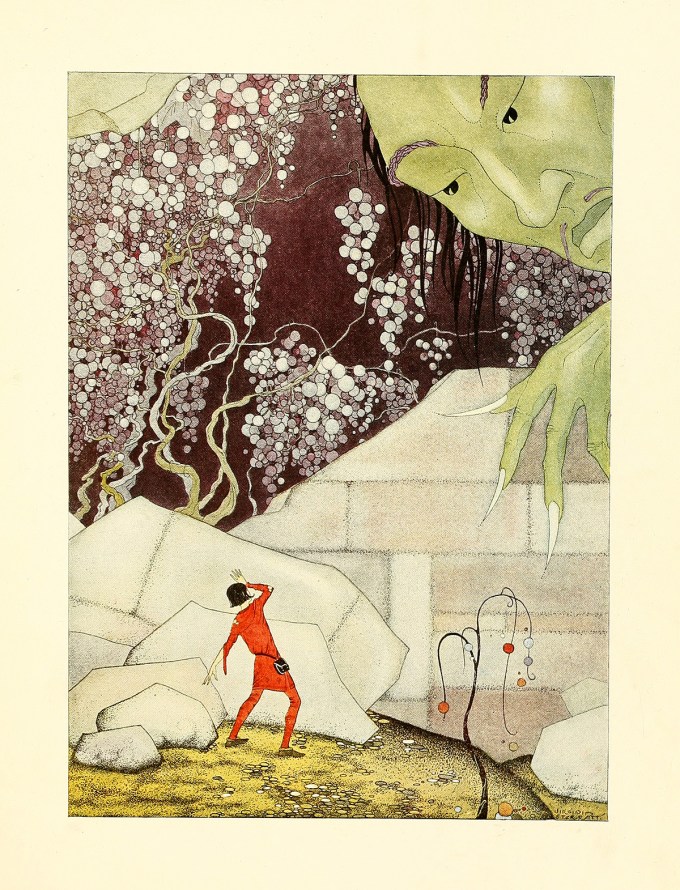

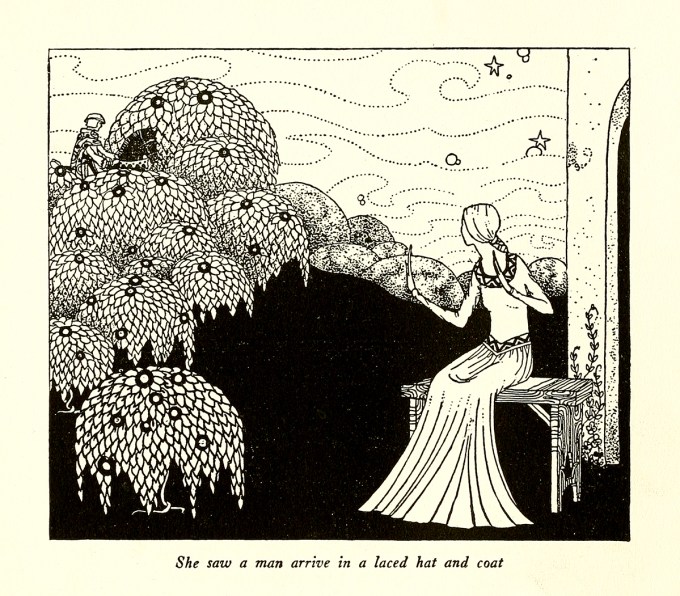

She especially loved that the publisher let her choose the passages most invigorating to her imagination and illustrate them in any way she was inspired to — which she did in a style reminiscent of Kay Nielsen’s Scandinavian fairy tale illustrations released several years earlier, yet distinctly her own, attesting to Nick Cave’s astute insight into influence and the paradox of originality.

After years of work through diminishing energies, her Arabian Nights was published in 1928. Local collectors immediately acquired the original drawings. Within a year, her art was lauded in the Los Angeles Times as technically brilliant and uncommonly imaginative, and exhibited in the Los Angeles Museum.

For this particular head-of-household teenage artist, it was nothing less than a lifeline that sustained her family for seasons.

Complement it with the story of artist Aubrey Beardsley — also a visionary of his era, also taken by tuberculosis at an even younger age — and his stunning illustrations for Oscar Wilde’s Salome, then revisit Dorothy Lathrop’s haunting fairy-poem dreamscapes, painted while Virginia was painting her French fairy tales.

Still, the California climate failed to halt the invasion of the deadly bacterium. Against the backdrop of her buoyant art, her young body wasted away in grim contrast. She left the rose-enveloped bungalow and entered a local sanatorium. Sixteen months later — an eternity for any young person, but especially one of such creative vitality — she was discharged as cured.

But she was only two months into her second year at the art academy when her mother grew ill. Now, it fell on Virginia to support her sisters and her only living parent by her art.

After the book was published in 1920, the publisher was so pleased that they immediately commissioned her to illustrate an edition of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Tanglewood Tales, published in 1921, followed by another commission for an adaptation of Arabian Nights, edited by Hawthorne’s granddaughter.

It was also a lifeline for the creative spirit that had been languishing as a handmaiden of consumerism in the vacuous world of commodity illustrations. Fairy tales were a natural fit for the fantastical imagination of the young artist. Since her earliest childhood, she seemed to dwell partway between the real world, with its disproportionate share of losses and hardships, and some otherworldly wonderland of levity and light — a wonderland Virginia could now bring to life for the world.

Virginia received 0 — more than ,000 a century of inflation later — for the cover art, eight watercolors, cover art, sixteen pen-and-ink drawings, and endpaper illustrations — staggering solvency for a teenager in any epoch, especially hers, when even grown women rarely earned this much in any professional field, especially art.

She entered a sanatorium and went on drawing in the tiny pockets of energy she had each day.

Upon her death, Missouri — where she had spent the formative years of early childhood after her father’s death — mourned a local hero of creative power. In a rueful remembrance published on the cover of the Sunday Magazine under the heading “The Girl Who Escaped from Life in Her Art,” alongside five large black-and-white reproductions of her drawings, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch made the bittersweet observation that although Virginia’s life had been a “struggle against poverty and disease,” spent in “prosaic places of the West and Middle West,” largely unrecognized beyond a small circle of admirers, in her short time she “left a record of achievement which most of those who live long and actively and receive public acclaim rarely achieve.”