Results:

As already noted, there were problems with the implementation of this survey. In particular, by tying participation to an active membership we effectively imposed a ‘paywall’—to quote a word used by a graduate student who could not easily get access—that likely biased our results (although in which direction is unclear). In retrospect the timing was particularly unfortunate, as the fact that the 2020 conference was cancelled meant that there were fewer active memberships than usual. However, it did mean that we could at least be sure that it was PSA members that were taking the survey. Those who may be planning to undertake such a survey within a larger or different community of philosophers need to consider carefully how to maximize participation while still targeting the right demographic.

Results of the Philosophy of Science Association’s Climate Change Survey

by Kerry McKenzie

After being asked to detail their experiences of engaging in research activities in a more online environment over the course of the pandemic, respondents were asked the following question:

1. Motivations

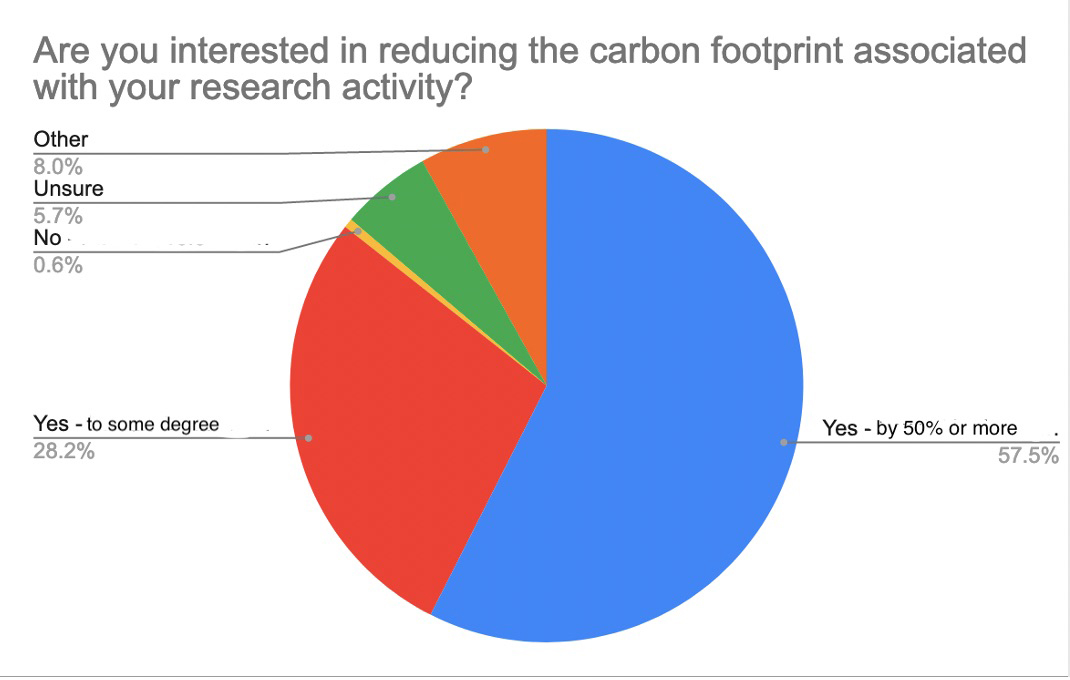

The United Nations International Panel on Climate Change states that a roughly 50% cut in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030, relative to pre-2020 levels, is necessary to avoid the worst consequences of climate change. Given this, are you interested in reducing the carbon footprint associated with your research activity in particular?

The options given were:

2. Implementation

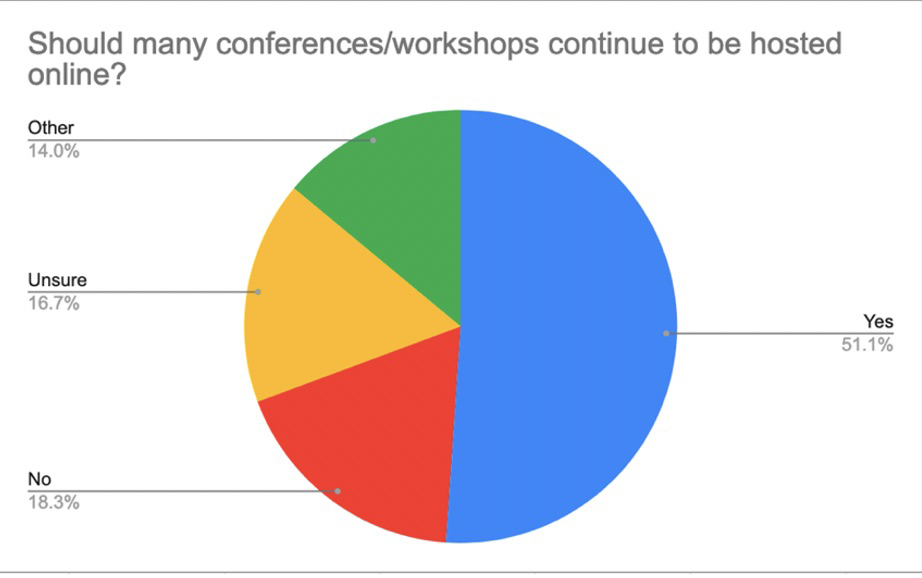

Respondents were then asked the question: ‘Given IPCC goals, do you think that many conferences and workshops should be hosted online?’ The options given were ‘Yes’, ‘No’, ‘Unsure’, and ‘Other’ (please explain).

3. Results

That’s one of several findings of a recent survey conducted by the Climate Task Force of the Philosophy of Science Association, discussed in the following guest post* by Kerry McKenzie, associate professor of philosophy at the University of California, San Diego.

[Cheyney Thompson, untitled]

- Yes — I would be interested in reducing it by 50% or more

- Yes — I would be interested in reducing it to some degree

- No — I would prefer my research activity to remain unaffected

- Unsure

- Other (please explain)

It is also worth reminding anyone planning more comprehensive surveys that—as anyone with experience here will know—getting the wording of questions right can be challenging (not least when the target audience is analytic philosophers!). Consider again the question reported on above: “The United Nations International Panel on Climate Change states that a roughly 50% cut in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030, relative to pre-2020 levels, is necessary to avoid the worst consequences of climate change. Given this, are you interested in reducing the carbon footprint associated with your research activity in particular?’’ At least one respondent thought that this question was ‘egregiously leading’. But we had worded this question carefully, deciding in the end that (i) the qualification that it was research activity in particular that was in question mitigated its ‘leading’ nature (given that one could reasonably be disposed to reduce one’s carbon budget but see research as sacrosanct), and (ii) breaking the question down into simpler questions produced something unwieldy and (frankly) patronizing, given our target audience. Clearly not everyone agrees that we made the right call here—the lesson being that those planning to issue future surveys will likely have to make difficult choices regarding wording.

Motivating the formation of the PSA CTF was the conviction that philosophers of science, and hence the PSA, must play a part in the global movement to slash global greenhouse gas emissions by approximately 50% by 2030 and to reach carbon neutrality by 2050, as urged by the IPCC. Its aims are to (a) help the PSA reduce the Association’s associated carbon emissions and (b) assist PSA members in their individual efforts as philosophers of science to achieve this goal.

During March 2021, the Philosophy of Science Association Climate Task Force (PSA CTF) issued a survey aimed at gathering information on members’ experiences of working in a more online environment as a result of the Coronavirus crisis and gauging attitudes towards continuing with some of these practices in the service of the climate crisis. Below are described (1) the motivations for this survey, (2) its implementation, (3) the most significant quantitative results, (4) some of their implications, and (5) some of the lessons learned in the administration of this survey that we hope will inform future efforts.

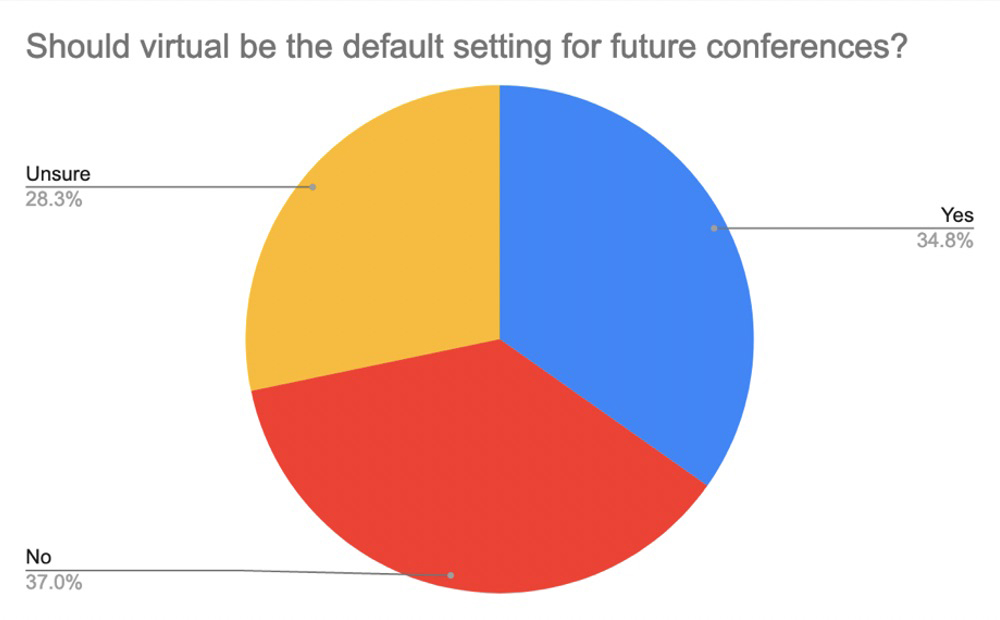

There was a pretty even split between ‘Yes’, ‘No’, and ‘Unsure’.

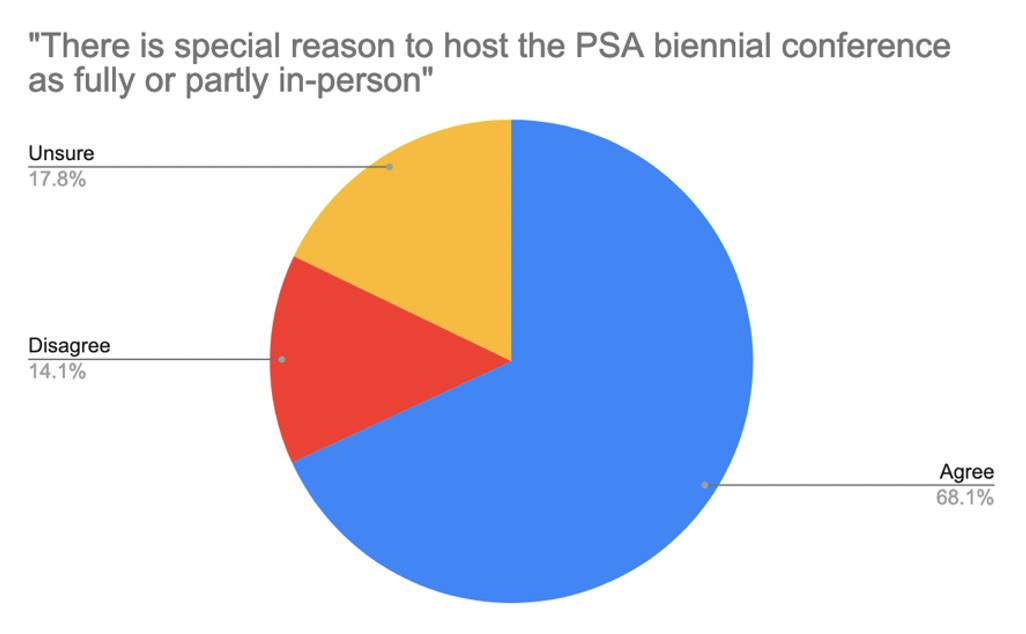

About two-thirds of respondents answered that there was special reason to continue to host the PSA meeting in person.

It is not the purpose of this report to explain or evaluate in any detail the reasons behind why one might or might not wish to move to a more online meeting model, partly as there has already been so much discussion on this forum of the pros and cons of online working from the point of view of environmental sustainability, access and inclusivity, and quality (see e.g. Daily Nous post here and Daily Nous post here). Those discussions have already made clear that there are dilemmas posed along almost every relevant dimension by both virtual and by in-person meetings; that no one model will work for everyone, at every career stage, and in every locale; that reasonable people disagree about the issue of the effectiveness of these sorts of interventions; and in sum, that there is a plurality of views on virtually every aspect of these issues that deserve to be respected. About half of respondents said ‘yes’. The remaining 50% was about evenly split between ‘no’, ‘unsure’, or had another response to the question.

Since aviation-incurred emissions are a very significant part of the carbon footprint of contemporary academic research, an urgent question is how philosophers of science as a community can reduce the amount of long-distance travel they undertake as part of their professional lives. Unlike questions of, say, how our campus offices are powered, this is a question that we as a community can have a direct impact upon via the choices we make as to what meetings we attend and how we organize those meetings. Since these choices will in turn be a function of what other philosophers are doing and willing to do in future, the question represents a collective action problem—hence a problem whose solution requires common knowledge of the views of the community. Hence, our decision to conduct the survey.

Finally, in retrospect we are unsure that we asked the most ‘actionable’ questions in this survey. Both the PSA CTF and our partner association Philosophers for Sustainability therefore invite input on what sorts of information other philosophers would regard as most useful from a planning perspective. Anyone with views on this issue can reach out to the Chair of the PSA CTF, Kerry McKenzie, or Philosophers for Sustainability via their website. Readers may also be interested to note that Philosophers for Sustainability are shortly (June 10th – 12th) running a Zoom conference on philosophy and the climate crisis, one focus of which will be a critique of extant research norms and strategies for changing them.

These we take to be the most significant quantitative results of the survey and the most useful for the community’s planning purposes. However, respondents were also invited to elaborate on their experiences of doing more workshops and conferences online. We will not enumerate these qualitative responses here—again, the comments in their entirety will soon be available to members via the PSA website—but suffice to say that in addition to some supportive comments it was clear that many respondents judged online conferences to be, in general, a pale imitation of in-person events. Some also enumerated ways in which they did not always better serve those with accessibility constraints. Others objected that focusing on academic travel was diverting attention away from other areas where we might more purposefully direct efforts against climate change.

The survey was made available through a portal on the PSA website and publicized through an email to everyone on the PSA mailing list; an active membership was then required to gain access to the survey. This ensured respondents were PSA members but arguably created other problems, as we describe in Section 5 below. Current membership of the PSA is around 700 and in the end almost 200 members (189) took the survey. The full results will soon be available to members via the PSA website and will inform a discussion during the President’s Plenary at the 2021 PSA meeting in Baltimore. The most significant results of the survey however are outlined below.

4. Interpretation

It is worth pointing out that the conflict that many philosophers of science seem to be experiencing between current professional norms and the challenge posed by the climate crisis evokes a scenario of ‘conscientious objection’ of the sort frequently discussed by bioethicists. In such scenarios, people experience a tension between their moral views and the expectations placed upon them as professionals—a tension which can result in them experiencing ‘moral injury’ as a consequence of doing their job. As is well known, many (though not all) bioethicists would argue that where the moral views concerned are not unreasonable, the correct response by their community is to minimize the professional harms suffered by those who refuse to engage in the practices that they regard as morally unacceptable—in part because moral injury should not be made a condition of doing one’s job. To be clear, the PSA CTF did not explicitly ask respondents whether they experience participating in a carbon-intensive research paradigm as a form of moral injury, or probe other relevant questions concerning morality that would be necessary to flesh out this claim. But regardless of the ultimate aptness of this analogy with conscientious objection, given the extent and the reasonableness of the desire of many in our community to reduce their research-associated carbon footprint, it behooves us as a community to determine the professional harms that may be associated with foregoing long-distance in-person meetings, and how these harms may be mitigated.

Respondents were then asked ‘Do you think that conference organizers should regard virtual as the “default” for meetings involving participants from distant geographic regions, moving to in-person only when they have good reason?’

Finally, we note that there was a clear signal sent to the PSA that most members wish this conference to continue to take place in-person. This raises the question of how the PSA can reduce its own carbon footprint, and what the relative benefits of small- versus large-scale conferences are.

Respondents were then asked to ‘Please consider the following statement: “Even if we assume that more workshops and conferences should take place remotely, there is special reason to host the PSA biennial conference as fully or partly in-person.” The options given for a response to this statement were ‘Agree’, ‘Disagree’, or ‘Unsure’.

5. Lessons for other organizations and for future surveys

Over half of respondents (100) said that they wished to reduce it by 50% or more. 85% (49 respondents) said they wished to at least reduce it by some degree. Only one respondent said they wanted it to remain unaffected. 10 were unsure, and 14 had another response to the question.

“There is a clear signal in these results that very many professional philosophers of science want to be working in a more online environment as a consequence of the climate crisis.”

However, given the high level of support shown by the results of this survey for making a very significant cut in our research-related carbon footprint and for assuming that online is the ‘default’ for conferences moving forward (other than the PSA biannual meeting), we think there is a clear signal in these results that very many professional philosophers of science want to be working in a more online environment as a consequence of the climate crisis. This should be of interest to conference organizers regardless of where they themselves sit on the issue. We should after all presume that the views expressed by the majority of respondents are not unreasonable, and as such that people who hold these views should not be deprived of the goods associated with interacting with participants from geographically distant regions.