Long before she became America’s preeminent philosopher, having arrived as a refugee, Hannah Arendt (October 14, 1906–December 4, 1975) was a young Jewish woman in Nazi-inflamed Germany, in love with an improbable beloved, writing a doctoral thesis about love that remains her least known but most soulful work: Love and Saint Augustine (public library) — an exquisite meditation on love and how to live with the fundamental fear of loss.

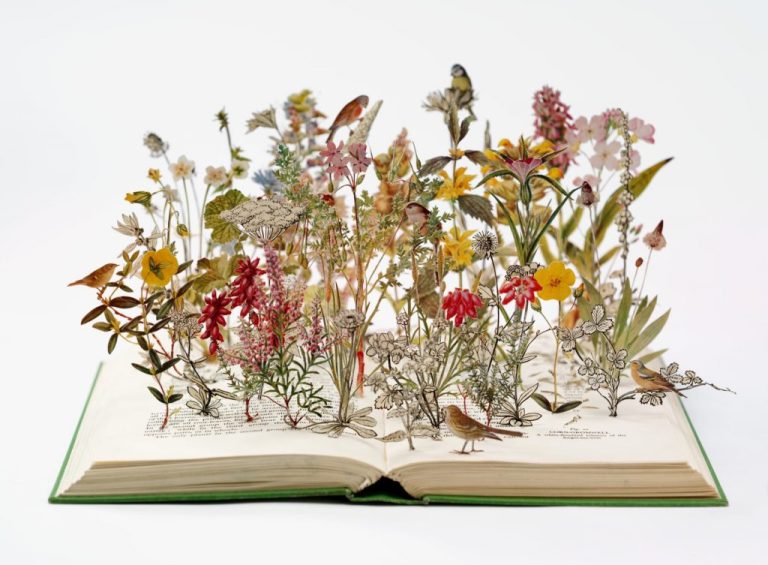

This is where the wisdom of lives that have already been lived can be of immense aid — a source of forward-facing resolutions, borrowed from people who have long died, having lived, by any reasonable standard, honorable and generous lives, lives of beauty and substance, irradiated by ideas that have endured across the epochs to make other lives more livable.

So began his Calendar of Wisdom: Daily Thoughts to Nourish the Soul, Written and Selected from the World’s Sacred Texts (public library) — a compendium of quotations by great thinkers of the past, annotated with Tolstoy’s own thoughts, which he compiled for two decades and published in the final ailing years of his life. (In some deep yet obvious sense, The Marginalian is my own lifelong version of such a compendium, commenced long before I first encountered Tolstoy’s book a decade ago.)

HANNAH ARENDT: LOVE WITHOUT FEAR OF LOSS

At the end of the month, in a sentiment Carl Sagan would come to echo in his lovely invitation to meet ignorance with kindness, Tolstoy writes:

[…]

Tracing Saint Augustine’s debt to the Stoics, Arendt considers how our attachment to the illusion of permanence and security limits our lives, and writes:

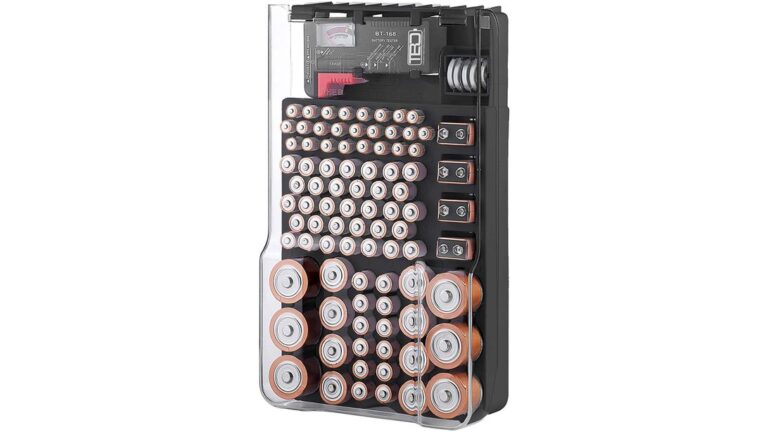

Creation is an act. Action takes energy.

[…]

[…]

[…]

Loving anybody and being loved by anybody is a tremendous danger, a tremendous responsibility.

SENECA: VANQUISH YOUR ANXIETY

We’ve got to be as clear-headed about human beings as possible, because we are still each other’s only hope.

If we abide by the common definition of philosophy as the love of wisdom, and if Montaigne was right — he was — that philosophy is the art of learning to die, then living wisely is the art of learning how you will wish to have lived. A kind of resolution in reverse.

But the greatest peril of misplaced worry, Seneca cautions, is that in constantly bracing for an imagined catastrophe, we keep ourselves from fully living — something on which he expounded in his most famous moral essay, On the Shortness of Life. He ends the letter with a quote from Epicurus illustrating this sobering point:

Even after her lyrical writing about the science of the sea won her the nation’s highest honor of literary art and her 1962 book Silent Spring catalyzed the environmental movement, making her the era’s most revered science writer, Carson continued making time to respond to letters from readers. In this superhuman feat — one downright impossible in our age of email, when millions of readers can reach a single writer’s inbox with the unmediated tap of a virtual button — Carson hauled trunkfuls of letters home, prioritizing those from students and young women asking her advice on writing. Responding to one of them, she offered:

More than a century after Mary Shelley celebrated nature as a lifeline to sanity and survival in a world savaged by a deadly pandemic, Frankl adds:

In most cases of people actually talking to one another, human communication cannot be reduced to information. The message not only involves, it is, a relationship between speaker and hearer. The medium in which the message is embedded is immensely complex, infinitely more than a code: it is a language, a function of a society, a culture, in which the language, the speaker, and the hearer are all embedded.

With an eye to the self-defeating and wearying human habit of bracing ourselves for imaginary disaster, Seneca counsels his young friend:

In another letter, writing to a young woman in whom Carson saw her younger self, she deepens and broadens the sentiment:

BERTRAND RUSSELL: BROADEN YOUR LIFE AS IT GROWS SHORTER

Reminding us that literacy is an incredibly nascent invention and still far from universal, Le Guin considers the singular and immutable power of spoken conversation in fostering a profound mutuality by syncing our essential vibrations:

In her 1987 masterpiece Beloved (public library) — which made her the first writer ensouled in a body with black skin and XX chromosomes to receive the Nobel Prize — she writes:

Kindness enriches our life; with kindness mysterious things become clear, difficult things become easy, and dull things become cheerful.

WALT WHITMAN: LIVE WITH ABSOLUTE ALIVENESS

In the thirteenth letter, titled “On groundless fears,” Seneca writes:

Make your interests gradually wider and more impersonal, until bit by bit the walls of the ego recede, and your life becomes increasingly merged in the universal life. An individual human existence should be like a river — small at first, narrowly contained within its banks, and rushing passionately past rocks and over waterfalls. Gradually the river grows wider, the banks recede, the waters flow more quietly, and in the end, without any visible break, they become merged in the sea, and painlessly lose their individual being.

In the final essay from the same forgotten treasure, Baldwin revisits the subject in what can best be described as a prose poem of eternal truth:

The sea rises, the light fails, lovers cling to each other, and children cling to us. The moment we cease to hold each other, the moment we break faith with one another, the sea engulfs us and the light goes out.

AND ONE FROM ME: CHOOSE THE EYES OF LOVE

You should respond with kindness toward evil done to you, and you will destroy in an evil person that pleasure which he derives from evil.

And yet, as he told Margaret Mead in their historic conversation, it is a responsibility to our own humanity:

The kinder and the more thoughtful a person is, the more kindness he can find in other people.