Philosophy is still a relatively small discipline in number of papers published per year at only(!) ~6,500 papers published in 2014 (listed in Web of Science). Note that the data don’t include books: to the extent the field still prizes (and cites) books over articles, our analysis may not fully reflect trends.

If Chu and Evans are correct, they realize that addressing the issue will be challenging:

I also think it is reasonable to wonder whether the relationship between citation churn and progress is consistent across disciplines. It would not surprise me to learn that, moreso in philosophy than most other disciplines, authors cite works with ideas they are criticizing and aiming to replace, and so citation consistency over time does not as strongly correlate with lack of innovation.

Some changes in how scholarship is conducted, disseminated, consumed, and rewarded may help accelerate fundamental progress in large fields of science. A clearer hierarchy of journals with the most-prestigious, highly attended outlets devoting pages to less canonically rooted work could foster disruptive scholarship and focus attention on novel ideas. Reward and promotion systems, especially at the most prestigious institutions, that eschew quantity measures and value fewer, deeper, more novel contributions could reduce the deluge of papers competing for a field’s attention while inspiring less canon-centric, more innovative work. A widely adopted measure of novelty vis a vis the canon could provide a helpful guide for evaluations of papers, grant applications, and scholars. Revamped graduate training could push future researchers to better appreciate the uncomfortable novelty of ideas less rooted in established canon. These measures, while not easy to implement across large fields, may help push scholarship off the local attractor of existing canon and toward more novel frontiers.

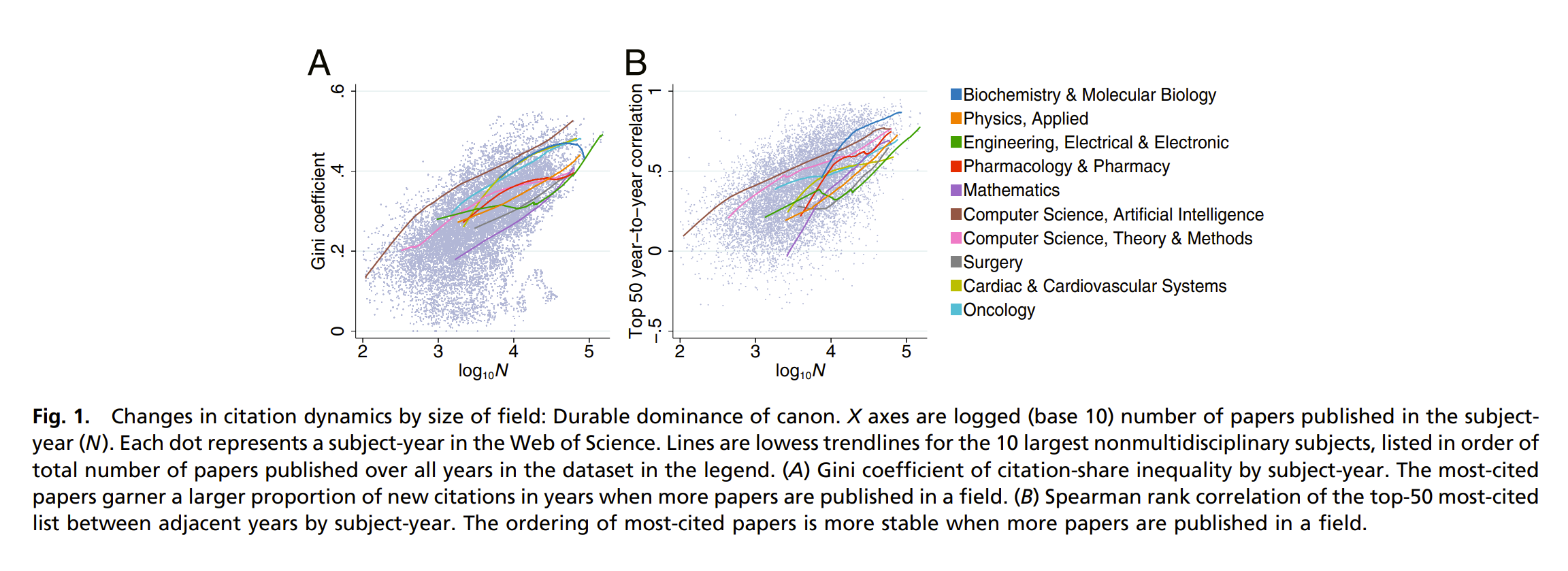

when the number of papers published per year in a scientific field grows large, citations flow disproportionately to already well-cited papers; the list of most-cited papers ossifies; new papers are unlikely to ever become highly cited, and when they do, it is not through a gradual, cumulative process of attention gathering; and newly published papers become unlikely to disrupt existing work. These findings suggest that the progress of large scientific fields may be slowed, trapped in existing canon…

When a field of study becomes large enough, its size “may impede the rise of new ideas,” according to Johan S.G. Chu and James A. Evans, in a new paper, “Slowed canonical progress in large fields of science,” in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

(via Molly Gardner via Eric Brown)

Nonetheless, they do offer some ideas—mainly changes to incentivize the production of novel work that could spur progress:

Discussion welcome.

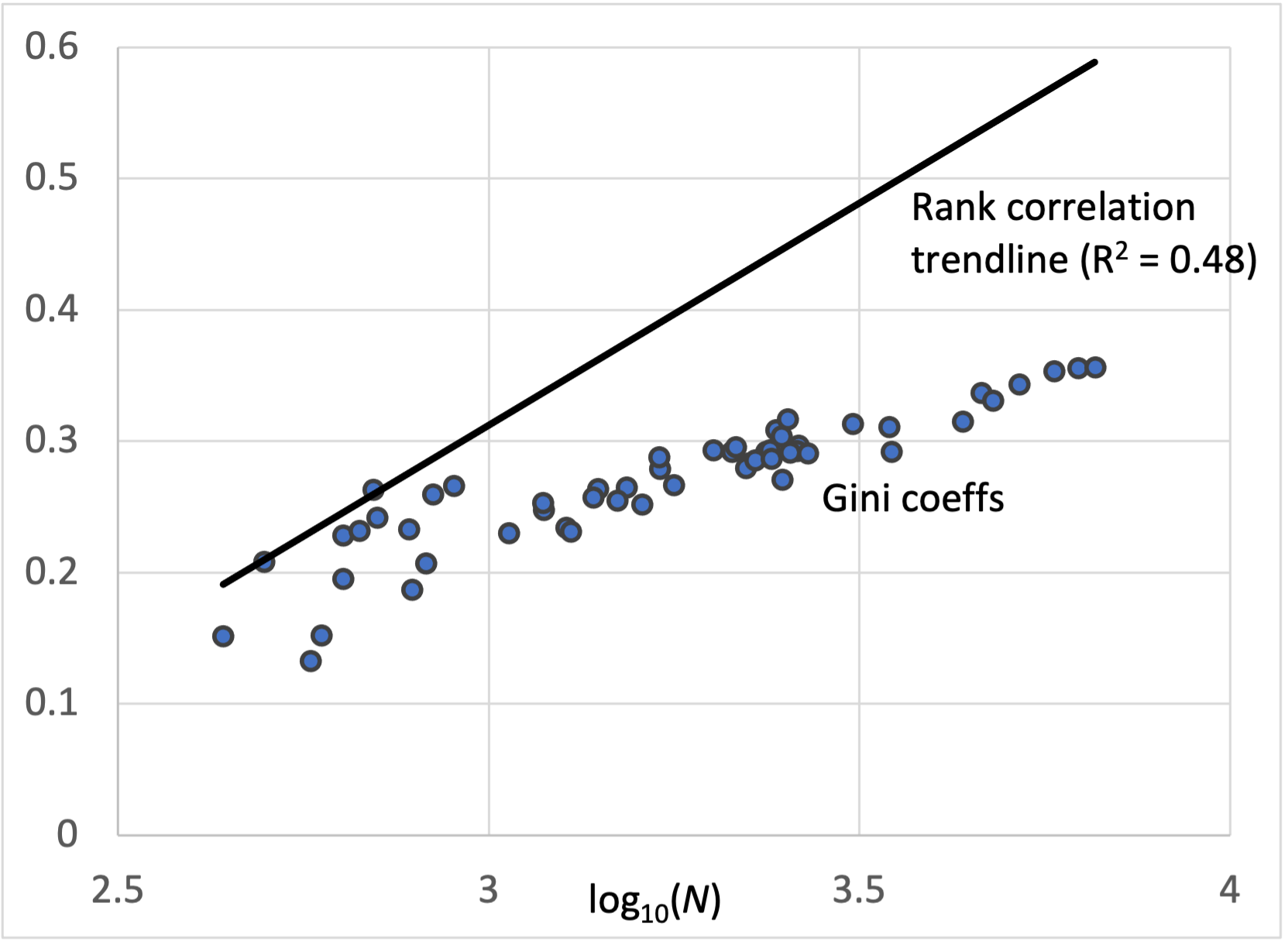

You can clearly see the trends. When the field has more papers published, top-cited articles garner a larger share of the field’s citations and the papers in the top-cited list and their rankings in the list change less over time.

The authors believe their findings are relevant to what they take to be the “more-is-better, quantity metric-driven nature of today’s scientific enterprise,” writing that “the scientific enterprise’s focus on quantity may obstruct fundamental progress.”

Examining 1.8 billion citations among 90 million papers across 241 subjects, we find a deluge of papers does not lead to turnover of central ideas in a field, but rather to ossification of canon…

Related: Citation Patterns Across Journals, Citation Problems in Philosophy—and Some Fixes, Philosophy Citation Practices Revisited, Philosophers Don’t Read and Cite Enough

Chu and Evans collected data which they claim support this explanation, finding that

It would be interesting to run this analysis across subfields in philosophy to see whether the larger subfields have less citation “churn” or are slower to produce ideas that “disrupt existing work.”

With these caveats, the dynamics we found in the paper still appear in the philosophy data.

Why is this? The authors believe that

I’ve attached a graph showing trends in the Spearman rank correlation of the top-50 most-cited papers from focal year to next (line) and Gini coefficients of citation concentration (circles). The x-axis is logged (base 10) number of papers published in the focal year.

too many papers published each year in a field can lead to stagnation rather than advance. The deluge of new papers may deprive reviewers and readers the cognitive slack required to fully recognize and understand novel ideas. Competition among many new ideas may prevent the gradual accumulation of focused attention on a promising new idea.

Canons crystallize as fields grow large. Churn in the identity and ordering of the most-cited papers decreases with larger field size. The pattern holds consistent when looking at data across all fields and at individual large fields across time… This crystallization of canon happens because the most-cited papers maintain their number of citations year over year when fields are large, while all other papers’ citation counts decay….

Reducing quantity may be impossible. Proscribing the number of annual publications, shuttering journals, closing research institutions, and reducing the number of scientists are hard-to-swallow policy prescriptions. Even if a scientist wholeheartedly agreed with the implications of our study, curtailing their output would be impractical given the damage to their career prospects and those of their colleagues and students, for example. Limiting article quantity without altering other incentives risks deterring the publication of novel, important new ideas in favor of low-risk, canon-centric work.

What about in philosophy? While the authors did not single it out for attention in their article, I got in touch with Professor Chu, who kindly analyzed the data for philosophy available from the Web of Science dataset. Here’s what he had to say: