Optimal hippocampal health appears to be — like the optimal experience of life itself — a matter of paying active and mindful attention, interrupting the “intentional, unapologetic discriminator” our brain has evolved to be, savoring the specifics of each unrepeatable moment.

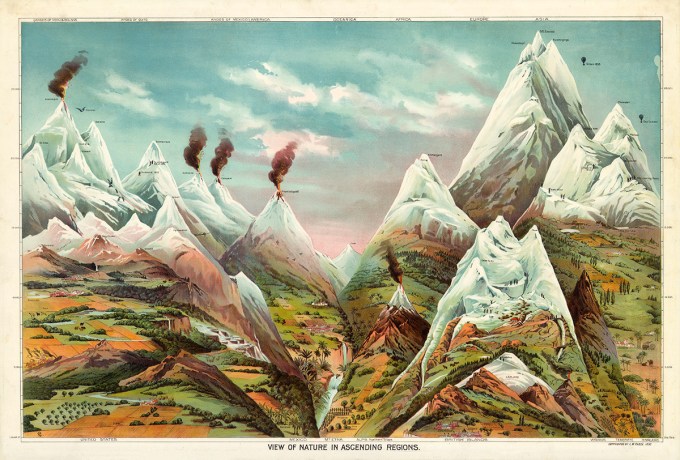

“Place and a mind may interpenetrate till the nature of both is altered,” the Scottish mountaineer and poet Nan Shepherd wrote in her lyrical love letter to her native Highlands, echoing an ancient intuition about how our formative physical landscapes shape our landscapes of thought and feeling. The word “genius” in the modern sense, after all, originates in the Latin phrase genius loci — “the spirit of a place.”

Often the places we grow up in have outsized influence on us. They influence how we perceive and conceptualize the world, give us metaphors to live by, and shape the purpose that drives us — they are our source of subjectivity as well as a commonality by which we can relate to and identify with others. Maybe it’s because of the vividness of their sensory impressions, their genius for establishing deep relationships to their early environments, that children have a strong capacity for the human emotion called topophilia.

In the remainder of the thoroughly fascinating Wayfinding, O’Connor maps the most thrilling shorelines of our evolving territories of understanding: astounding findings indicating that people from migratory populations have measurably longer alleles of the dopamine receptor gene associated with exploratory behavior than people from sedentary communities; ancient feats of navigation passed down the generations in native cultures to challenge the Western social theory of culture; music as a metaphor for the relationship between organisms and their environment. For a lyrical counterpart, complement it with Rebecca Solnit’s Field Guide to Getting Lost.

Besides their intricate internal timekeeping mechanisms, many nonhuman animals are endowed with equally intricate space-mapping mechanisms. Each migration season, humpback whales travel more than ten thousand miles far from land to return to the precise place where they were born. There are bird species — European pied flycatchers, blackcaps, and indigo buntings among them — that appear to orient by the pole star in their nocturnal flight; there are insect species — ants and bees among them — that perform triumphs of trigonometry with their light-sensitive photoreceptors, calculating spatial distances by polarized light to find the most direct route home after a winding pathway of foraging. With their mere milligram-brains of one million neurons — a grain of sand to the Mont Blanc of our eighty-six billion — and 20/2000 vision that renders them blind by human standards, honeybees make hundreds of foraging trips per day, meandering many miles from home, then compute the “beeline” back. African ball-rolling dung beetles, Namibian desert spiders, and southern cricket frogs use the stars of the Milky Way as their compass, just like some of the most courageous members of our own species once used the constellations to find their way to freedom from the moral cowardice of tyranny: To ensure they were moving northward, migrants on the Underground Railroad were instructed to keep the river on one side and “follow The Drinking Gourd” — an African name for Ursa Major, or The Big Dipper.

Life on earth has created millions of Ulyssean species undertaking epic journeys at scales both large and small. Getting lost is a uniquely human problem. Many animals are incredible navigators, capable of undertaking journeys that far eclipse our individual abilities. The greatest migration on earth belongs to the Arctic tern, a four-ounce argonaut that travels each year from Greenland to Antarctica and back again, a distance of some forty-four thousand miles. Flying with the wind, the tern’s return itinerary is a globe-trotter’s fantasy, circumnavigating Africa and South America.

[…]

[…]

That string is known as autonoeic consciousness, from the Greek noéō: “I perceive,” “I fathom” — our capacity for mental self-representation as entities in time that can reflect on our own lives as continuous and coherent phenomena of being. In the blink of evolutionary time since the dawn of neuroscience in the 1930s, one area of the brain has emerged as the crucible of both our autoneoic consciousness and our spatial navigation: the hippocampus. O’Connor writes:

[…]