In the following guest post, Michael Prinzing (Yale) discusses trends in philosophical discussions of happiness and well-being.

Philosophy’s Happiness Literature: More of It, More Empirical

by Michael Prinzing

Journal Citation Reports, a database of academic journals, includes 320 journals classified as philosophy journals. I selected the 50 most-cited of these and queried Web of Science for all the articles from those journals that included the terms happiness, well-being (or wellbeing), or “the good life” in the title, abstract, or keywords. This yielded 673 records, dating as early as 1947. After removing a duplicate record and non-articles (some records were book reviews, editor’s notes, etc.) there were 521 papers. Collectively, these 521 articles cited 7,389 sources. However, many of these were cited very few times. Only 318 received at least 5 citations. I categorized each of these 318 sources as either scientific or non-scientific, depending on whether the source is dedicated to reporting or reviewing empirical findings. Thus, this definition does not include journals that occasionally publish empirical findings—e.g., Noûs or Synthese. But it does include sources like the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (this was the most-cited scientific source, with 78 citations.) It also includes sources like the American Economic Review, which, though it does not publish novel empirical results, is dedicated to reviewing empirical research. Of the 318 sources, 111 were scientific. 5 could not be categorized because it was impossible to determine the exact source from the abbreviated title given by Web of Science, or whether the source was scientific. These were: P BRIT ACAD, CRITICAL NE IN PRESS, DROP, VALUE ETHICS EC, WELL BEING. I then used this categorization to determine how many scientific sources each of the 521 philosophy papers cited.

Methods

To investigate this question, I conducted a bibliometric analysis of articles published in the 50 most-cited philosophy journals on the topics of happiness, well-being, and the good life. (For those interested, I describe my methods at the bottom. The data and R code are available here.)

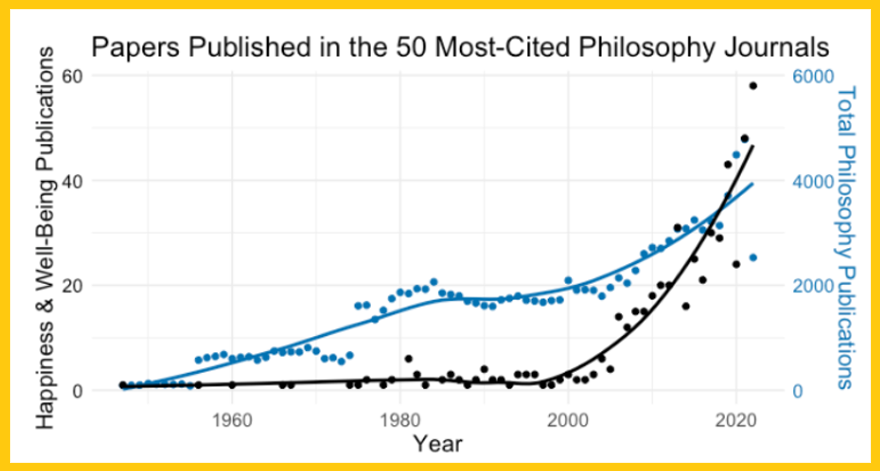

Things look very different when we turn to papers on happiness, well-being, and the good life. That trend is illustrated by the black line (scale on the left). There we see no growth at all until the turn of the millennium. At that point, the number of publications skyrocketed. Hence, this sub-discipline does seem to stand out from the general trend in philosophy. Moreover, whatever is going on in the philosophy of happiness and well-being, it seems to have started around the turn of the millennium. It’s possible that this has something to do with the rise of “Positive Psychology,” which also emerged at that time. That field of psychological research may have provided fertile ground for philosophers interested in similar topics. Or, perhaps some broader societal trend led to increased interest in happiness and well-being among both philosophers and psychologists.

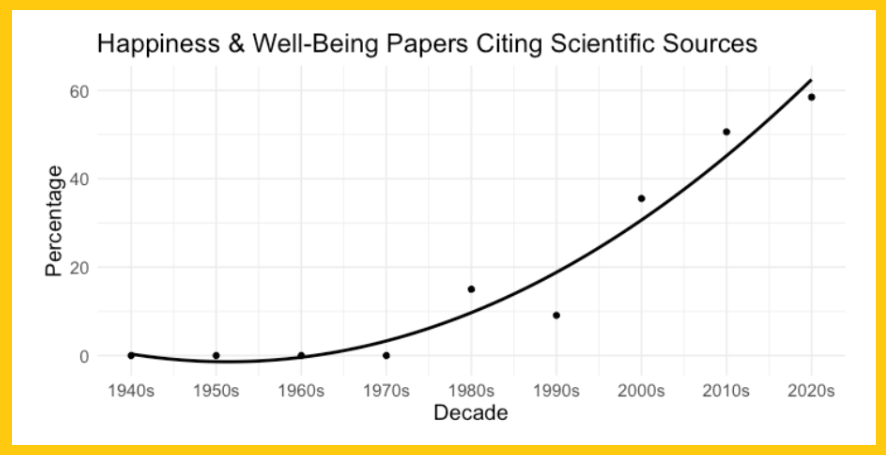

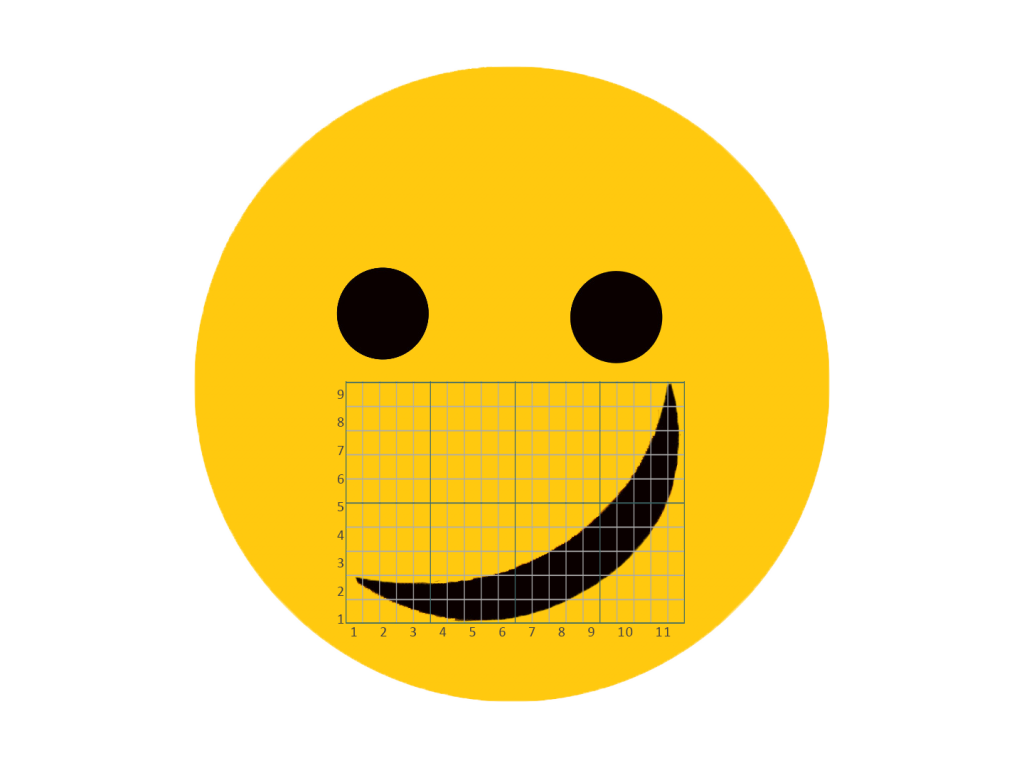

The second figure, below, illustrates the proportion of papers on happiness and well-being that cited scientific sources. Since there were so few publications per year during the 20th century, I grouped the papers by decade. Prior to the 1980’s, not a single paper cited any scientific sources. In the 1980’s and 90’s, about 10-15% of papers did so. In the 2000’s the proportion jumped to about 35%, and since 2010 papers citing scientific sources constitute the majority.

Overall, then, it seems that not only have happiness, well-being, and the good life become much more popular topics of philosophical discussion, that discussion is increasingly intertwined with empirical research. Indeed, papers in the philosophy of happiness and well-being that don’t engage with scientific research are now in the minority.

Something seems to be happening in the philosophy of happiness and well-being. Philosophers seem increasingly interested in what’s going on in the social and health sciences. Some philosophers are even conducting empirical research of their own. But is this a widespread phenomenon, or just a small subset of a sub-discipline?

Obviously, in the past 50 years or so, there has been a general trend of increasing publication volume—and not just in philosophy. That trend is illustrated by the blue line in the figure below. The blue line (scale on the right) represents the total number of papers published in the top 50 philosophy journals since the mid-20th century. Although growth leveled off a little between 1980 and 2000, there appears to have been fairly steady growth since the 1950’s.