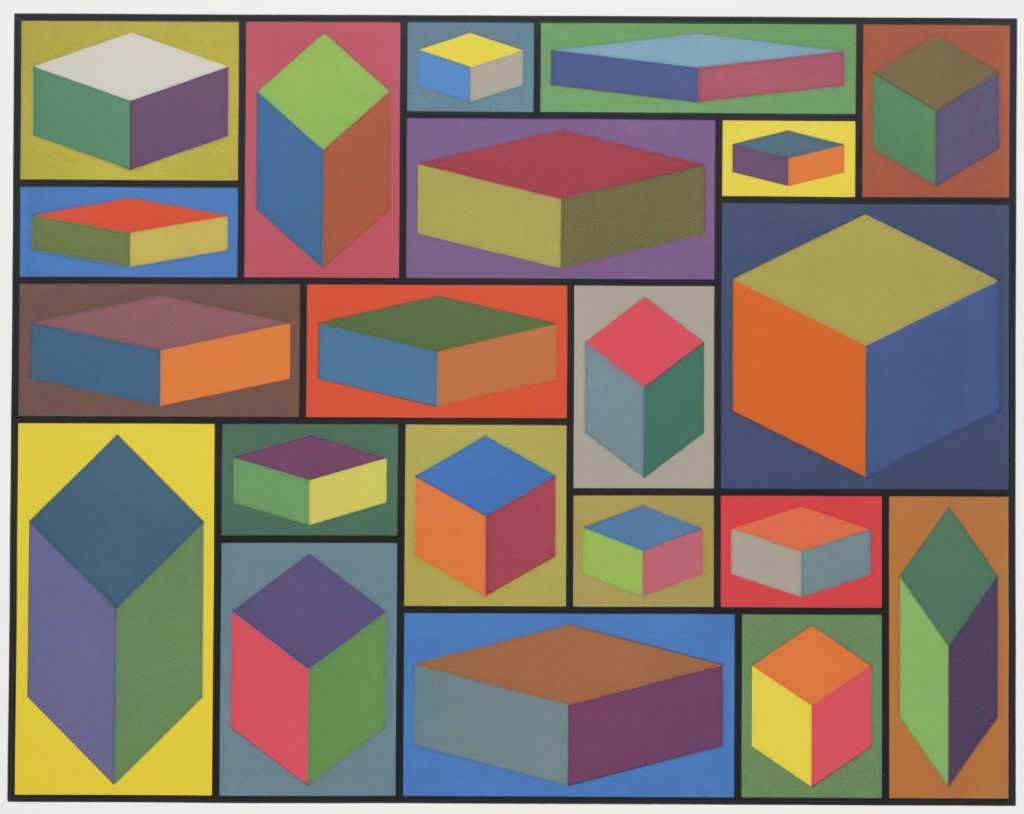

[Sol LeWitt, “Distorted Cubes (B)”]

Many colleagues end up with an idealized subjectivist account… or some souped up version of hedonism, or objective list theory with [a] clever subjective requirement, and so on. I call these the Big Three (but I don’t care if I am wrong about that, maybe in fact there are Big Four or Big Five). In any case these theories are pretty much unusable in practice. They are far too abstract and they lack what in philosophy of science we call, ‘bridge principles’. Philosophers do not think it’s their job to translate these theories into practical constructs or measures because such a translation is too complicated, too empirical, and our big journals won’t publish such work. Fine, but then don’t complain when the fruits of your labor aren’t taken into account by practitioners and don’t accuse them of being theoretically unsophisticated (they often are, but it’s your job to get out of your armchairs and do something about that). The whole situation strikes me as dysfunctional, but thankfully it’s changing. Colleagues in applied ethics and political theory are far more comfortable building theories that help practitioners satisfy Value Aptness.

A “responsible definition of wellbeing,” says Anna Alexandrova (Cambridge), “needs to be appropriate to the goals of the project—epistemically accessible, reasonably simple, in other words fit for purpose… Philosophers of wellbeing in the analytic tradition think very differently.”

Professor Alexandrova’s answer continues:

You can read the whole interview with her at 3:16 AM. Discussion welcome.

The traditional inquiry about what well-being fundamentally consists in is wrong-headed, says Alexandrova, who argues for “construct pluralism” rather than a singular, unified account:

Construct pluralism is just the consequences of Value Aptness. To be apt a theory of wellbeing needs to be adjusted to the context of its use and because there are many such contexts, we shall need many constructs. For me construct pluralism is both an empirical fact and a desirable goal. I think when you look at all the fields in which people use a concept of wellbeing, you see diversity. Wouldn’t it be a shame if development economists defined wellbeing in the same way as developmental psychologists? Thankfully they don’t and I get nervous when I hear people advocate a single definition of wellbeing for all purposes.

That is from a discussion of the matter of “value aptness,” or “How can the science of wellbeing properly produce knowledge that is genuinely about well being?” Interviewer Richard Marshall had asked, “Why do you think your question of Value Aptness leads you to think that philosophers at the moment are not thinking about the right things needed to answer this question?”