In an entry penned in the middle of weeklong Independence Day party at his friend Allen Ginsberg’s house in Harlem, the twenty-five-year-old Kerouac uses the word “beat” as an adjective for the first time, a year before he formally introduced the term “Beat Generation” to describe New York’s underground nonconformist creative youth.

Over months and months of “ascetic gloom and labor,” he produced 300,000 words sprawling across 1,200 manuscript pages, populated with characters that embodied his own multitudes — the romantic poet with the existential bend, the stoical grief-stricken mother, the Village hipster, the indomitable wanderer, the perennial lost soul.

Just before he turned twenty-four, Kerouac watched his father Leo slip out of life with the mortal agonies of stomach cancer — his father, who had risen to America from a long lineage of potato farmers in rural Quebec; his father, in whose print shop Jack had nursed his childhood dreams of becoming a writer; his father, whom he saw as the only person capable of reconciling spiritual values with Americanism.

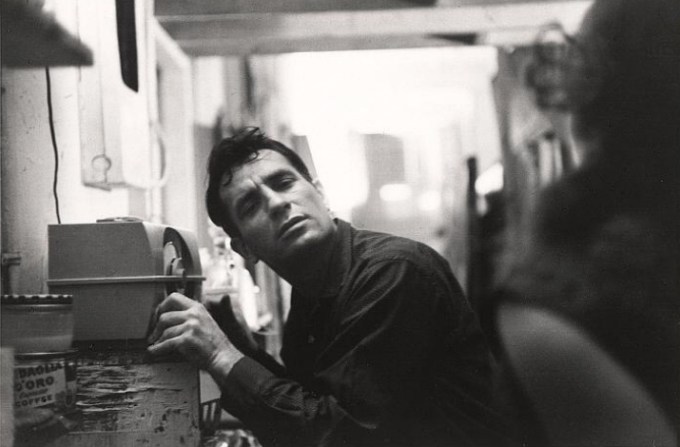

The youngest of three children in a working-class family, Jack Kerouac (March 12, 1922–October 21, 1969) yearned to be a writer by the time he was ten. He began keeping a journal at fourteen and never stopped. Everywhere he went, he carried a spiral notebook or a railroad brakeman’s ledger. He called the journals his “work-logs,” “mood logs,” “scribbled secret notebooks,” using them to “keep track of lags, and digressions, and moods.” He filled their pages with streams of thought and feeling, reckonings with what it means to be human and what America means, punctuated by drawings and riddles, psalms and haikus.

On July 3, 1947 — a sweltering Saturday — he writes:

God it’s a strange sea-light over all this… We are in the bottom of some ocean; I never realized it before. In my phantasy of glee there is no sea-light and no beatness, just things like the wind blowing through the pines over the kitchen window on an October morning. I’ll have to start pulling all these new things together now. And this is why men love dualisms… they cannot get away from them… and they feel independent and wise among them… And they choose about and stumble on to death and the end of phantasy. (or beginning.)

There was Hunkey — in this evil dawn — telling me he had seen Edie in Detroit and told her that I still loved her. What a surprise that was! — how strange can Hunkey get? Hunkey scares me because he has been the most miserable of men, jailed & beaten and cheated and starved and sickened and homeless, and still he knows there’s such a thing as love, and my stupidity… and what else is there in Hunkey’s wisdom? What does he know that makes him so human after all he has known? — it seems to me if I were Hunkey I would be dead now, someone would have killed me long ago. But he’s still alive, and strange, and wise, and beat, and human, and all blood-and-flesh and staring as in a benny depression forever. He is truly more remarkable than Celine’s Leon Robinson, really so. He knows more, suffers more… sort of American in his wider range of terrors. And do I love Edie still? — The wife of my youth? Tonight I think so, I think so. And what does she know? And where are we all?

Just like Steinbeck used his journal as a tool of discipline and a hedge against self-doubt while composing his own masterwork, Kerouac continued using his notebook as an integral part of his creative process. “Doubt is no longer my devil, just sadness now,” he wrote in it more than a year after his father’s death, as the novel began taking its final shape. Later, he would compress the epoch of heartache and creative fury in a single spartan statement: “I stayed home all that time, finished my book and began going to school on the GI Bill of Rights.”

He couldn’t have known it then, the way we can never foretell the way the confusions of the present imprint the hallmarks of the future, but in grieving his own father, the young Jack Kerouac was becoming the Father of the Beat Generation.

In a passage that presages his later pull to Buddhism and its salutary teachings of nondualism, he adds:

In this waking dream, this deja-vu of life, his friend Herbert “Hunkey” Huncke appears — a scrappy sporadic writer and petty thief bedeviled by chronic addiction, whose affable candor had made him a beloved fixture of the New York Beat world. The dreamt-up Hunkey comes bearing news of Kerouac’s first wife turned lifelong friend — the woman to whom he would write his most beautiful letter a decade later. Now, in the sweltering stupor of youth and grief, on the pages of his journal, he goes on to coin the epochal use of “beat”:

Two years later, in an entry strikingly evocative of the young Sylvia Plath’s largehearted (and bittersweet in hindsight) life-resolution in her own journal, Kerouac points in words what would always remain the central animating spirit of his art and life:

Adrift in the ether of grief, Kerouac struggled to make sense of life and loss and his young self. He turned to the only self-salvation he knew: On his mother’s kitchen table in working-class Queens, he set out to write the great American novel. There, he would make of himself a Melville for the twentieth century, but always with a strain of Whitman — of that soulful sensitivity to the bittersweet dimension of life, that secret kinship with the lonesome, the melancholy, the outcast, who are often most awake to beauty.

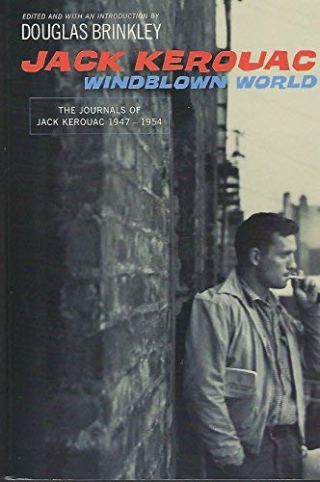

The previously unpublished journals he kept in that period, collected in Windblown World: The Journals of Jack Kerouac 1947–1954 (public library), contain not only the record of his self-creation but the creation of the Beat ethos itself.

Complement this fragment of the altogether breathtaking Windblown World with Melville on the mystery of what makes us who we are, then revisit his reflections on kindness and the self illusion, the crucial difference between talent and genius, his “30 beliefs & techniques” for writing and life, and the stirring story of the night Kerouac kept a young woman from taking her own life.

To get to the hymn of images, the facts of living mystery… I spent another 3 days without eating or sleeping to speak of, just drinking and wineing and squinting and sweating. There was a vivacious girl right out of the Twenties, redhaired, distraught, sexually frigid (I learned.) With her I walked 3½ miles in a Second Avenue heat wave (on Monday this is) till we got to her “streamlined Italian apartment” where I lay on the floor looking up out of a dream. Seems like I had sensed it all before. There was misery, and the beautiful ugliness of people.

I shall keep in contact with all things that cross my path, and trust all things that do not cross my path, and exert more greatly for further and further visions of the other world, and preach (if I can) in my work, and love, and attempt to hold down my lonely vanities so as to connect more and more with all things (and kinds of people), and believe that my conscience of life and eternity is not a mistake, or a loneliness, or a foolishness — but a warm dear love of our pour predicament which by the grace of Mysterious God will be solved and made clear to all of us in the end, maybe only.