From the far-seeing platform of her eighty-seventh year, she observes:

Noting that “whenever you give her a chance, nature returns,” Goodall reflects on why she makes an annual pilgrimage to a friend’s cabin on the banks of the Platte River in Nebraska to watch the migration of the sandhill cranes, the snow geese, and other waterbird species:

Two and a half millennia ago, while devising the world’s first algorithm and using it to revolutionize music — that hallmark of our humanity — Pythagoras considered the purpose of life, concluding that we must “love wisdom as the key to nature’s secrets.”

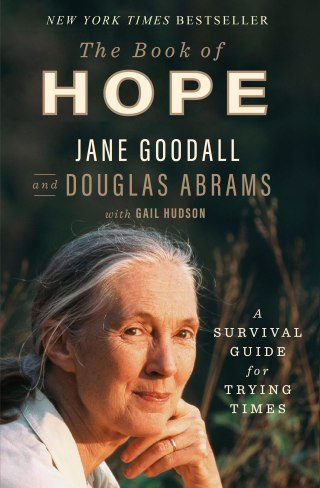

Complement this fragment of the altogether inspiriting Book of Hope with Rachel Carson on the ocean and the meaning of life, Alfred Russell Wallace’s prophetic prescription for ecological wisdom, and this century-old field guide to wonder by Anna Bostford Comstock — the forgotten woman who laid the groundwork for the youth climate action movement — then revisit Jane Goodall’s lovely letter to children about how books shape lives, including her own.

We humans have nothing to add to that wisdom, for we are a product of it — but we can and do detract from it and imperil nature’s resilience with our unwise actions. Against this backdrop, the greatest measure of own wisdom might be the wherewithal and willingness to get out of the way.

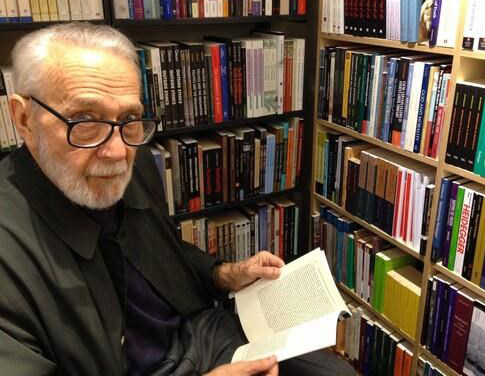

Across the abyss of epochs and civilizations, Jane Goodall — another sage for the ages, who revolutionized our understanding of nature with her paradigm-shifting, hubris-dismantling discovery that toolmaking is not the hallmark of humanity alone — considers the meaning of wisdom in The Book of Hope: A Survival Guide for Trying Times (public library), the record of her soaring, life-spanning conversation with writer Douglas Abrams.

Wisdom involves using our powerful intellect to recognize the consequences of our actions and to think of the well-being of the whole. Unfortunately… we have lost the long-term perspective, and we are suffering from an absurd and very unwise belief that there can be unlimited economic development on a planet of finite natural resources, focusing on short-term results or profits at the expense of long-term interests.

A great deal of our onslaught on Mother Nature is not really lack of intelligence but a lack of compassion for future generations and the health of the planet: sheer selfish greed for short-term benefits to increase the wealth and power of individuals, corporations, and governments. The rest is due to thoughtlessness, lack of education, and poverty. In other words, there seems to be a disconnect between our clever brain and our compassionate heart. True wisdom requires both thinking with our head and understanding with our heart.

I hear echoes of the great nature writer Henry Beston’s splendid century-old meditation on human belonging and the web of life, in which he bowed before the ancient wisdom of nonhuman animals and the primeval forces that animate them with effortless aliveness. “In a world older and more complete than ours,” he wrote, “they move finished and complete, gifted with extensions of the senses we have lost or never attained, living by voices we shall never hear.”

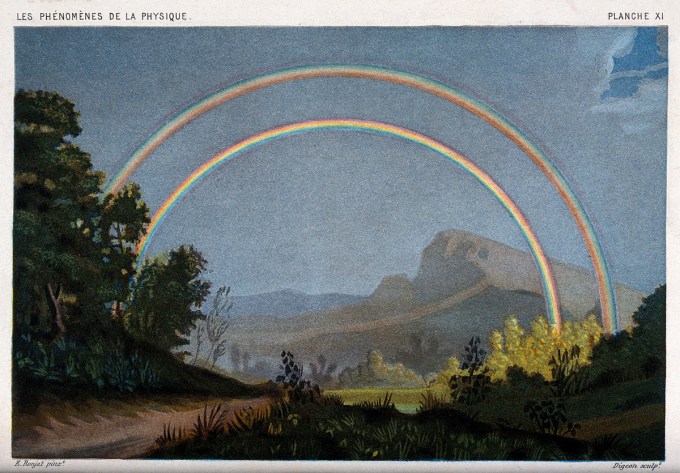

Shakespeare says it beautifully when he talks of seeing “books in the running brooks, sermons in stones, and good in everything.” I get a sense of all of this when I stand transfixed, filled with wonder and awe at some glorious sunset, or the sun shining through the forest canopy while a bird sings, or when I lie on my back in some quiet place and look up and up and up into the heavens as the stars gradually emerge from the fading of day’s light.

[…]

This conviviality animates the spirit in which Jane Goodall moves through the world, the way in which she sees nature’s wisdom across the entire spectrum of existence, from the creaturely to the cosmic — wisdom always greater than our own, to which our highest contribution is the humility of seeing it and the ability of letting it inspire acts of reverence that fill our human lives with beauty and meaning, be that in the form of a poem or an observatory.

An essential part of this needed human wisdom, she intimates, is the humility of recognizing nature’s own wisdom, which governs its extraordinary resilience — the “blind intelligence,” in poet Jane Hirshfield’s lovely phrase, that gave us “turtles, rivers, mitochondria, figs” — the rawest optimism we know.

The hallmark of wisdom is asking, “What effects will the decision I make today have on future generations? On the health of the planet?”

This loss of the telescopic perspective is a betrayal of our very nature — “most definitely not the behavior of a ‘wise ape,’” she laments. More than half a century of progress and plundering after Rachel Carson issued her passionate deathbed appeal to the next generations to step up to the reality that humanity “is challenged, as it has never been challenged before, to prove its maturity and its mastery — not of nature, but of itself,” Goodall reflects:

She reflects:

After deconstructing our ample misunderstandings of what hope really means and defining it not as passive optimism but as the motive force of rightful action — “a human survival trait” without which “we perish” — she turns to the essence of wisdom as the tool that calibrates our hope and aims it at the correct action.

Because it is a dramatic reminder of the resilience we have been discussing. Because despite the fact that we have polluted the river, despite the fact that the prairie has been converted for growing genetically modified corn, despite the fact that the irrigation is depleting the great Ogallala Aquifer, despite the fact that most of the wetlands have been drained — the birds still come every year, in the millions, to fatten up on the grain left after the harvest. I just love to sit on the riverbank and watch the cranes fly in, wave after wave against a glorious sunset, to hear their ancient wild calls — it is something quite special. It reminds me of the power of nature. And as the red sun sinks below the trees on the opposite bank, a gray, feathered blanket gradually spreads over the whole surface of the shallow river as the birds land for the night, and their ancient voices are silenced. And we walk back to the cabin in the dark.

I hear deep consonance with contemporary ecologist David Abrams’s science-soulful reflection on the wisdom of the more-than-human world, in which he observed that “we are human only in contact, and conviviality, with what is not human.”

I hear in Goodall’s awe echoes of Emily Dickinson — here is her “thing with feathers,” alighting to the riverbank in its ancient grandeur — hope not as metaphor but as ecological reality of this living world, so old and so radiant with self-renewal: the native poetry of nature.