People can’t, unhappily, invent their mooring posts, their lovers and their friends, anymore than they can invent their parents. Life gives these and also takes them away and the great difficulty is to say Yes to life.

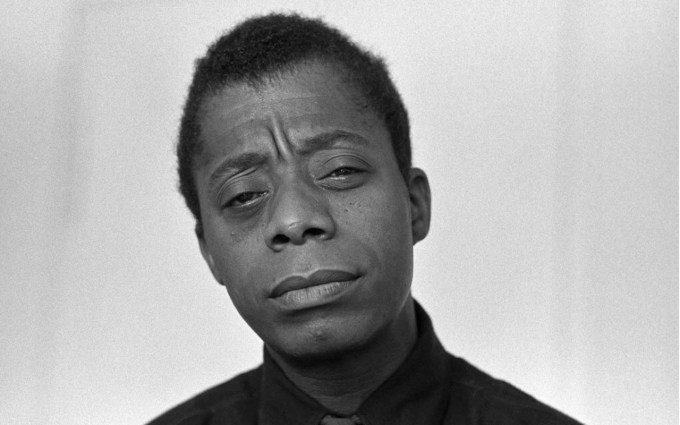

James Baldwin (August 2, 1924–December 1, 1987) was a young man — young and brilliant and aflame with life, blazing against society’s illusion of stability and control — when he composed his stunning semi-autobiographical novel Giovanni’s Room (public library), making the paradox of freedom its animating theme.

And yet, within these narrow parameters of being, nothing appeals to us more than the notion of freedom — the feeling that we are free, that intoxicating illusion with which we blunt the hard fact that we are not. The more abstract and ideological the realm, the more vehemently we can insist that moral choice in specific situations within narrow parameters proves a totality of freedom. But the closer the question moves to the core of our being, the more clearly and catastrophically the illusion crumbles — nowhere more helplessly than in the most intimate realm of experience: love. Try to will yourself into — or out of — loving someone, try to will someone into loving you, and you collide with the fundamental fact that we do not choose whom we love. We could not choose, because we do not choose who and what we are, and in any love that is truly love, we love with everything we are.

Baldwin writes:

Complement with Toni Morrison on the deepest meaning of freedom and Simone de Beauvoir on how chance and choice converge to make us who we are, then revisit Baldwin on the doom and glory of knowing who you are.

Nothing is more unbearable, once one has it, than freedom.

In the final years of his life, he would look back on the crucible of these ideas, describing Giovanni’s Room as a book not about one kind of love or another but “about what happens to you if you’re afraid to love anybody.” In his most intimate interview, he would recount the best advice he ever received on the transcendent, terrifying choicelessness of love and the implicit, seemingly paradoxical demand for choice within it — advice given him by an old friend:

Exactly half a century after the Spanish-American poet, philosopher, and novelist George Santayana considered why we like what we like and a decade after the Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl made his hard-earned case for saying yes to life in the most unfree of circumstances, Baldwin writes:

To bear the unbearable, Baldwin intimates, we construct and cling to artificial structures of choice, personal and social — habits, routines, the contractual commitment of marriage, the moralistic frameworks that indict one kind of love as good and another as bad. Today, Giovanni’s Room is celebrated as a pioneering liberation and representation of LGBTQ+ love — a term that did not exist in Baldwin’s day, for it speaks to a cultural silence so deep then that there was no adequate language for it. (The language we use today is hardly adequate — but language is always a placeholder for a culture’s evolving understanding of itself, the space in which we work out our concepts as we learn how to think about them in learning how to speak of them.) Baldwin rose against a tidal force of cowardice from publishers at a time when the Bible of psychiatry — the Diagnostic Manual of Mental Disorders — classified love as so many of us know it as a “sociopathic personality disturbance.” At the center of his act of courage and resistance is the recognition that the experience of love is our most primal confrontation with the illusion of freedom.

We, none of us, choose the century we are born in, or the skin we are born in, or the chromosomes we are born with. We don’t choose the incredibly narrow band of homeostasis within which we can be alive at all — in bodies that die when their temperature rises above 40 degrees Celsius or drops below 20, living on a planet that would be the volcanic inferno of Venus or the frigid desert of Mars if it were just a little closer to or farther from its star.

You have to go the way your blood beats. If you don’t live the only life you have, you won’t live some other life, you won’t live any life at all.

Four years later, Baldwin would develop these ideas in his immensely insightful speech-turned-essay on freedom and how we imprison ourselves.