His great and then-radical insight was that true intimacy requires room for spontaneity, without the freedom of which we fall back on pretense and control, and back into games. Spontaneity, he observed, can only spring from unalloyed awareness, or what contemporary pop psychology calls “presence.”

Awareness means the capacity to see a coffeepot and hear the birds sing in one’s own way, and not the way one was taught… A few people, however, can still see and hear in the old way. But most of the members of the human race have lost the capacity to be painters, poets or musicians, and are not left the option of seeing and hearing directly even if they can afford to; they must get it secondhand. The recovery of this ability is called here “awareness.”

And yet strokes are inherently transient and superficial, feeding not the soul but the self, and games are dysfunctional ways of obtaining them in the first place — for they trade in insincerity and perpetrate a betrayal of ourselves, the other person, or both.

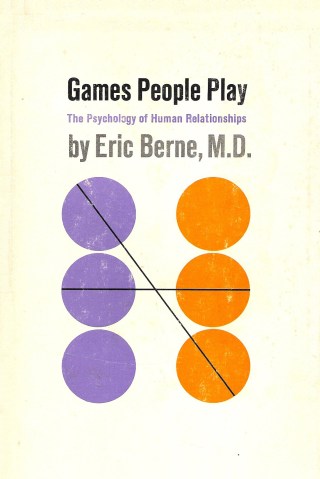

Sensing that his model would help people in unexpected ways, Berne pooled his savings and borrowed money from friends to pay a publisher to publish his handbook on human relationships. Games People Play (public library) — uncommonly insightful, unfussy, deeply humane — not only changed the landscape of psychology but forever stamped the body of popular culture with its parlance. When Kurt Vonnegut reviewed the book in LIFE Magazine in 1965, he exulted in its “brilliant, amusing, and clear catalog of the psychological theatricals that human beings play over and over again,” slaking our “anguished need for simple clues as to what is really going on,” outlining archetypal interactions full of themes “all sadly or sweetly or cruelly familiar.”

Berne captures the plain truth of it all, which can feel so beyond reach:

Berne writes:

But beyond the simplest and most complementary exchange — one Adult issuing the stimulus, another Adult giving the response — most of social transactions are a chaos of mismatched and ever-switching ego states. The confusion — the wounding — happens when the lines of communication cross and the interaction becomes not between two people in parallel and consistent ego states, but between one part of one person and a different part of the other: Child-Adult, Adult-Parent, Parent-Child, and all the other possible non-equivalences. This basic pattern, a diagram of which became the book’s cover, is what defines a game — “an ongoing series of complementary ulterior transactions progressing to a well-defined, predictable outcome” — a patterned, self-defeating psychological interchange, in which one ego state issues a stimulus concealing the emotional need of another ego-state, then receives a response to the hidden message and reacts negatively to it, frustrating both parties and garbling communication in a way that injures intimacy.

Like anything original and widely resonant, Berne’s model was flattened and commodified. In the miniature industry of pop psychology that has mushroomed from the mycelium of his ideas, warping them beyond recognition in various representations and interpretations. But read in the original, even with its dated language and its ready reminders that even the farthest seers are still a product of their time, Games People Play remains a rich and surprising handbook for that most difficult of human tasks: understanding ourselves, so we can cease misunderstanding and mistreating each other.

At the heart of Berne’s model are three ego states that live in each of us: the Child (the most natural, vulnerable, and spontaneous part of our personality, keeper of our creative vitality and our most unalloyed capacity for pleasure); the Parent (the part of us that unconsciously mimics the psychological responses of our parents as we observed them in childhood); and the Adult (the competent and self-possessed part of us capable of making sound decisions in our best interest). All three coexist within us, and all three play into our social interactions. Berne writes:

“Beautiful friendships” are often based on the fact that the players complement each other with great economy and satisfaction, so that there is a maximum yield with a minimum effort from the games they play with each other. Certain intermediate, precautionary or concessional moves can be elided, giving a high degree of elegance to the relationship. The effort saved on defensive maneuvers can be devoted to ornamental flourishes instead, to the delight of both parties.

The first rule of communication is that communication will proceed smoothly as long as transactions are complementary; and its corollary is that as long as transactions are complementary, communication can, in principle, proceed indefinitely.

In our adult lives, he argues, our strokes are aimed at three primary needs: structure (a way to organize our days and hours in a meaningful way), stimulus (those vitalizing nuggets of experience that awaken us from the trance of near-living to light life up with meaning), and recognition (the affirmation of our fellow human beings that what we are doing with our days and hours matters to the world). All the strokes we play for are variations on these three primal hungers.

Intimacy begins when individual (usually instinctual) programing becomes more intense, and both social patterning and ulterior restrictions and motives begin to give way. It is the only completely satisfying answer to stimulus-hunger, recognition-hunger and structure-hunger.

One consequence of how fundamental these psychological patterns are — patterns that make for great literature and heartbreaking love — is that every relationship is in some sense and to some extent a game, or reliant on games for its endurance. But although games are inherently dishonest, even in the morally forgivable way of being played by people simply opaque to themselves, there are degrees of integrity with which we can play them. In one of the loveliest passages in the book, Berne writes:

The aware person is alive because he* knows how he feels, where he is and when it is. He knows that after he dies the trees will still be there, but he will not be there to look at them again, so he wants to see them now with as much poignancy as possible.

We play games, Berne argues, in order to obtain the strokes we were accustomed to in childhood, extorting them from others in our adult life — something he terms racketeering. Consequently, what we end up obtaining are affirmations of our existing beliefs about ourselves, laid down in our formative years, reinforcing our basic existential stance in a way that trades in victimhood rather than agency. Unable to ask for what we really need — because it is too vulnerable-making and demands too much trust — we end up playing for strokes that are invariably compromises on what we most hunger for, simulacra of the deepest satisfaction: real intimacy.

The hardest thing in life isn’t getting what we want but knowing what we want, for it requires the whole blooming buzzing confusion of knowing who and what we are — the great question we are always answering with our lives for as long as we live. Most of our psychological suffering and most of the pain we inflict on others stem from our confusion about what we want and all the consequent clumsiness with which we go after it, like a child fumbling with a toy before she has learned how to operate her own body or what the toy does.

Echoing E.E. Cummings’s admonition that we often mistake other people’s knowledge and beliefs for the raw reality of what we feel, Berne considers what awareness really means:

When all the games fall away, the highest prize of human relationships — which is also the hardest and most terrifying — is not some particular stroke but intimacy. Emerson captured this as his only truly intimate relationship made him shudder with the recognition that “there is no terror like that of being known.”

Fortunately, the rewards of game-free intimacy, which is or should be the most perfect form of human living, are so great that even precariously balanced personalities can safely and joyfully relinquish their games if an appropriate partner can be found for the better relationship.

Because real intimacy is such a hard-won glory and demands so much of us — including, often, the overriding of our primal patterns — we habitually lean on games as our default self-soothing and self-regulation mechanisms. With his boundless humanistic sympathy for our predicament and his native optimism, Berne writes:

The twin roots of our awareness, Berne argues, are spontaneity and intimacy:

[…]

[…]

[…]

For certain fortunate people there is something which transcends all classifications of behavior, and that is awareness; something which rises above the programing of the past, and that is spontaneity; and something that is more rewarding than games, and that is intimacy. But all three of these may be frightening and even perilous to the unprepared.

Intimacy means the spontaneous, game-free candidness of an aware person, the liberation of the eidetically perceptive, uncorrupted Child in all its naiveté living in the here and now.