“When you realize you are mortal,” the polymathic poet, painter, journalist, novelist, and philosopher Etel Adnan (b. February 24, 1925) wrote in her sixtieth year while wresting wisdom from the mountain, “you also realize the tremendousness of the future. You fall in love with a Time you will never perceive.”

Born in Beirut and educated in Paris, Adnan was then living at the foot of Mount Tamalpais in California, teaching philosophy at a local university, painting and writing poetry — the polyphonous calling through which she soon met the Lebanese-American artist Simone Fattal, now her partner of half a century, who has made the most astute observation about Adnan’s paintings of rising and setting celestial bodies, horizons perched on infinity, and mountains rising toward eternity: that they do for us what icons used to do for believers, conferring upon our everyday lives a certain supranatural energy, an aura of awe at the sheer miracle of existence.

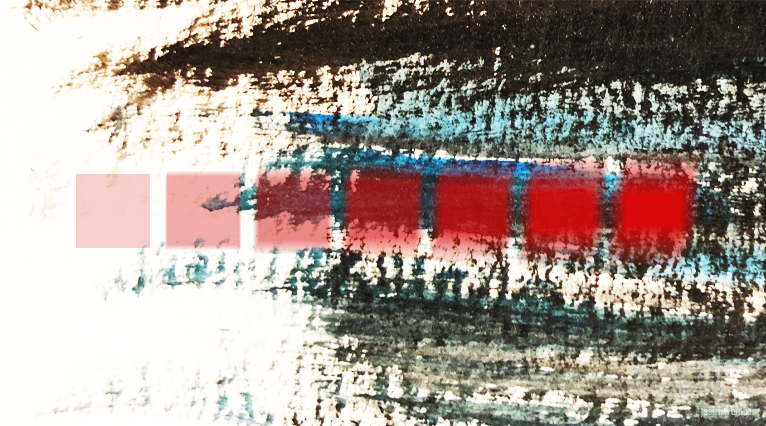

Funeral March for the First Cosmonaut is the first artwork greeting the wonder-smitten visitor to Light’s New Measure — the Guggenheim Museum’s retrospective of Adnan’s work, launched midway through her ninety-seventh year, titled after a line from her 2012 poetry collection Sea and Fog:

there are potholes in the skyes

familiar to the wanderers of the sierras

moving icebergs which taste like

antimatter when physics go wild

Gagarin Scott Gherman Titov McDivitt

Komarov the new hierarchy of archangels

bringing messages from outer space

decoding the protons and moving under

a shower of travelling electrons.

Complement with Umberto Eco’s semiotic children’s book The Three Astronauts, written and painted in the same era, then revisit astronaut Leland Melvin reading Pablo Neruda’s love letter to Earth and poet Sarah Kay performing her ode to awe, “Astronaut.”

Seven sunrises for a cosmonaut!

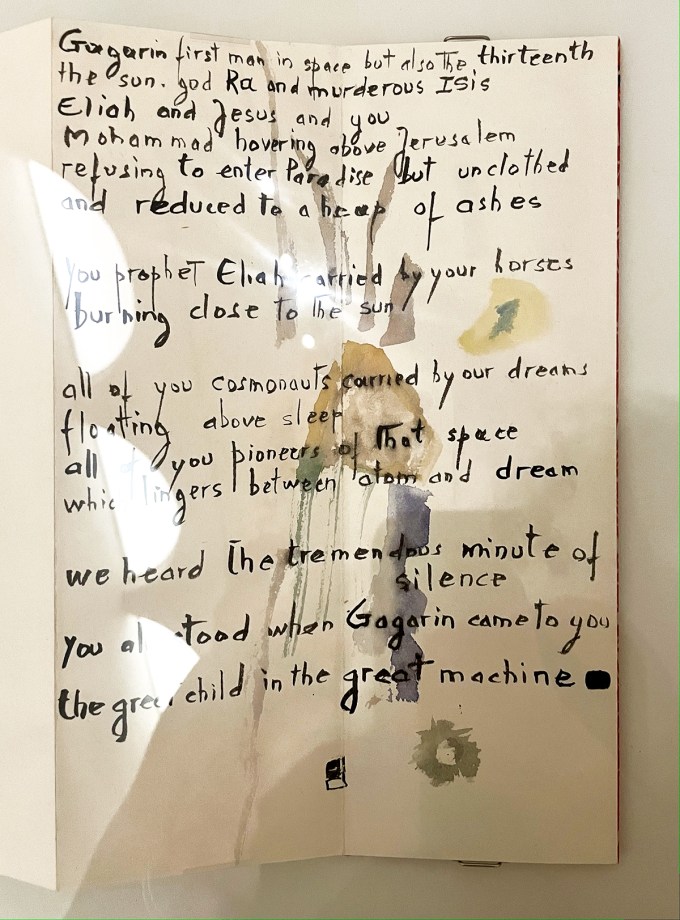

In 1961, the Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin had become the first human animal — of all the hundred-some billion of us who ever lived and died — to leave the planet on which we had evolved several million years earlier. It was an era of terror and wonder — science had swung open new portals of possibility for knowing the miracle of life more intimately, and politics had hijacked science to build new weapons for destroying that miracle.

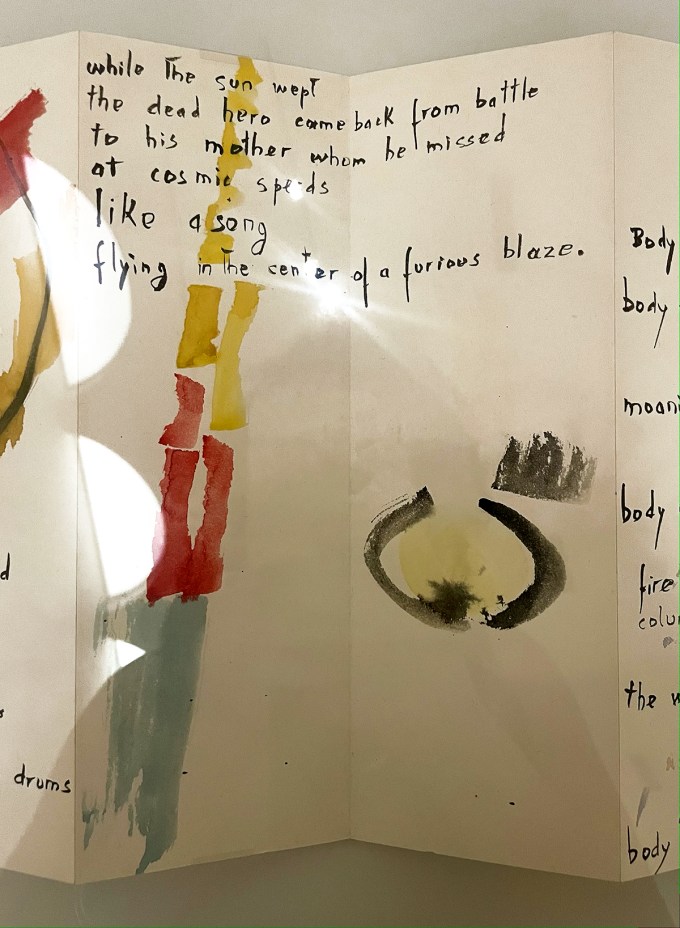

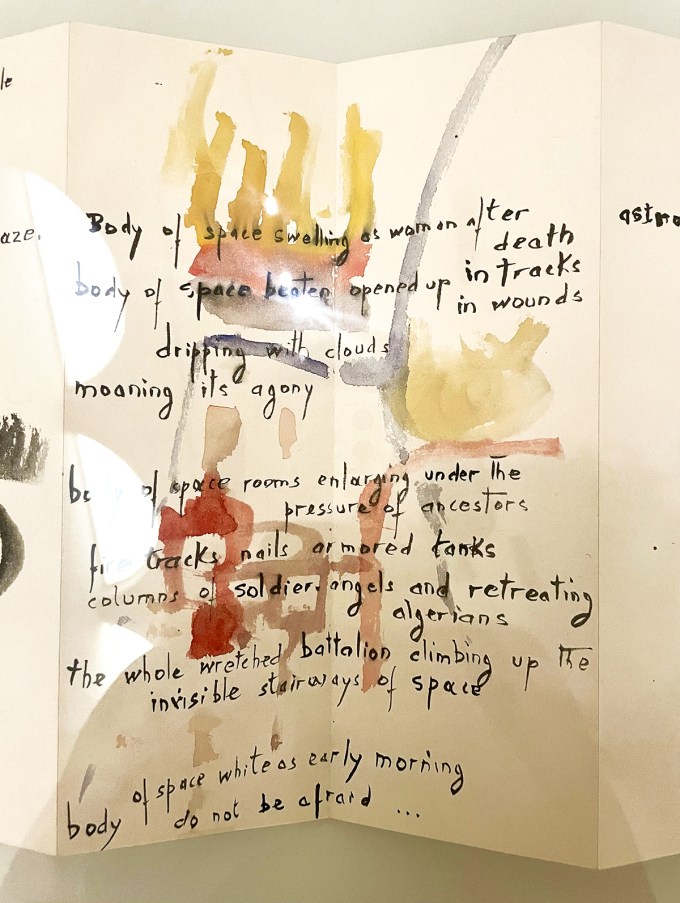

These questions of space, time, morality, and transcendence, which continue to permeate Adnan’s century-wide body of work and wonder, had come into formative focus two decades earlier, in one of her most original and unexampled works: a hybrid of poetry and painting — a new form Adnan christened leporello, after the Italian bookbinding term for concertina-folded leaflets — reflecting on a triumphal and tragic moment in the history of our species.

seven sunsets for a single evening

and the uninterrupted moon

growing into their eyes with the look

of mothers looking back on us from the other

side of our deaths

In 2019, having just turned 94 and living in Paris with her partner, Adnan collaborated with the German composer and sound artist Ulrike Haage on adapting Funeral March for the First Cosmonaut into an experimental radio requiem — a kind of spacetime sound installation, beautiful and haunting, fusing musical elements from the classical tradition of Gagarin’s native Russia and the ancient Middle Eastern tradition of Adnan’s native Beirut, embodying the opening verse of the poem’s third sequence:

When Gagarin perished in a plane crash seven years later under mysterious circumstances, Adnan composed an eleven-part epic poem in ink and watercolor, titled Funeral March for the First Cosmonaut — at once a memorial for the new Icarus and new scripture for the human mythos of space, painted into an accordion book, exploring the largest questions of existence: life, death, loneliness, longing, creation, destruction, the relationship between the ephemeral and the eternal, our relationship to the cosmos and to each other.

you were searching through the hands of the monkey tree

that pipeline to the sky

a light incoherent like a wave

was moving behind the clouds

and you went swimming into that distant

pool you went to be suspended there

cool as the western side of palm leaves

under the break of noon

Funeral March for the First Cosmonaut is an elegy for humanity in the classic sense, a hybrid of celebration and lamentation — an elegy for us creatures forever “eating and remaining hungry,” “kissing and remaining lonely,” “speaking and remaining doomed”; creatures who bomb and imprison each other, but who also never cease to “struggle towards freedom, struggle toward meaning” with the fury of a song. In this respect, it is kindred to Maya Angelou’s staggering poem “A Brave and Startling Truth,” which voyaged into the cosmos aboard the Orion spacecraft a generation later.

The heart is a stranger to patterns of matter or their distribution. In darkness, light’s new measure.

In the beginning was the white page

In the beginning was the Sufi in orbit

In the beginning was the sword

In the beginning was the rocket

In the beginning was the dancer

In the beginning was color

In the beginning was music