Look dearest Ethel…. Please live 50 years at least; for now I’ve formed this limpet childish attachment it can’t but be part of my simple anatomy for ever — wanting Ethel — I say, live, live, and let me fasten myself upon you, and fill my veins with charity and champagne.

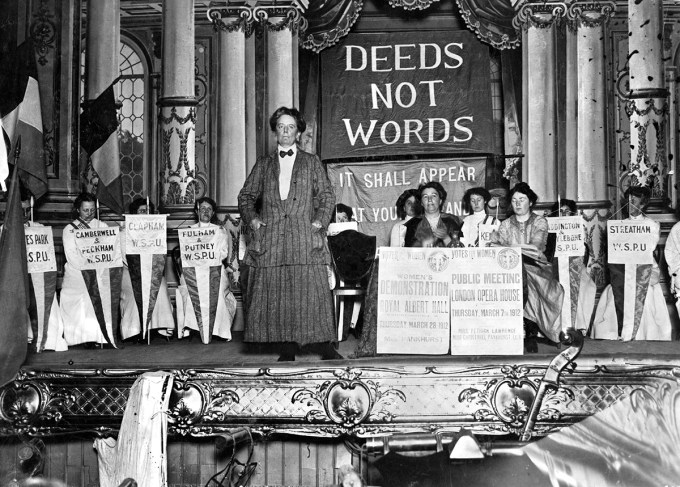

Having perfected her craft in Florence, Smyth made her debut as a composer of orchestral music in London’s Crystal Palace with her soulful Serenade in D. She was thirty-two. But it wasn’t until late middle age, when she was already losing her hearing, that her work finally began gaining the commensurate recognition. Her 1911 choral suite “Songs of Sunrise” became the official anthem of the suffrage movement, known as “The March of the Women.”

In her late seventies, writing in the final memoir As Time Went On (public domain), Smyth notes that neither she nor anyone she knows dare class themselves with Beethoven in matters of his ability or disability, but she shares in his orientation to the creative impulse beneath the physical limitation. While recognizing that what helped Beethoven soar through his deafness was that it struck him when he was “a young man and in the full tide of inspiration,” Smyth declares with a defiant buoyancy that the musician in her “won through in the end,” for inspiration lives outside the bounds of time and age:

“Tell me nothing of rest,” the young Beethoven bellowed when he began losing his hearing, resolving to “take fate by the throat” despite his disability. A century later, another trailblazing composer of uncommon artistic ability took her own fate by the throat as she faced the same embodied disability.

If you are still in possession of your senses, gradually getting accustomed, as some people do, to a running accompaniment of noises in your head; if instead of shrinking from the very thought of music you suddenly become conscious of desire towards it… why, then anything may happen… and once more you begin to dream dreams.

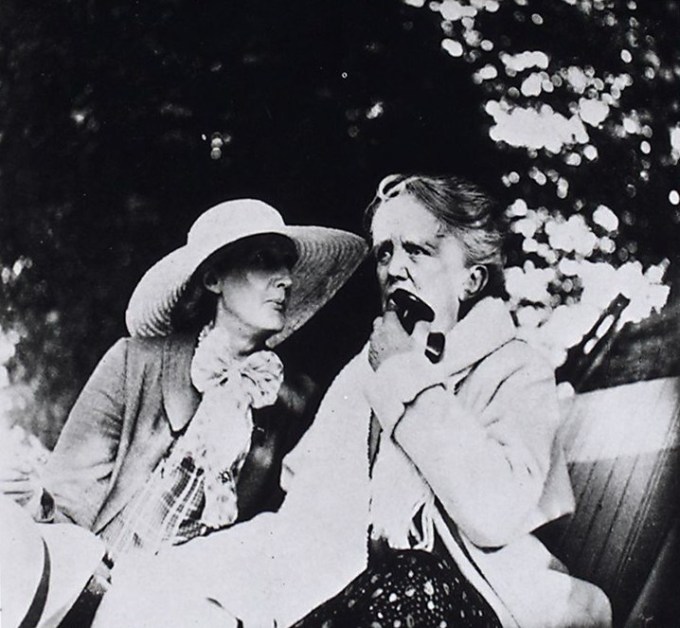

From across the hall, Woolf observed Smyth seated next to the Queen in the Royal Box and made a heartbreaking note in her diary of how the composer leapt to her feet at the wrong moment, thinking that the National Anthem was being played.

But although by the end of her life she was as highly regarded as Tchaikovsky and Brahms, Smyth was sidelined by the collective selective memory we mistake for history and was all but forgotten within a generation — partly because, unlike other queer women of her epoch and every epochs before and many epochs since, she refused to yield to the cultural pressure to marry a man anyway, thus leaving no heirs to steward her intellectual property and artistic legacy; partly because her music was never recorded in her lifetime — something conductor James Blachly and his inspired Experiential Orchestra set out to remedy a century later in the world’s first crowdfunded symphony orchestra reanimation of a previously unrecorded piece, triumphantly earning Smyth a posthumous Grammy nomination. [embedded content]

Complement with some of humanity’s greatest writers on the power of music and the legendary cellist Pablo Casals, writing at age ninety-three, on creative vitality and how working with love prolongs your life, then revisit What Color Is The Wind? — a most unusual serenade to the senses, inspired by a blind child — and the story of how the trailblazing queer sculptor Harriet Hosmer paved the way for women in art a generation before Smyth.

Smyth had dedicated her 1919 autobiography to the memory of Lady Mary Ponsonby — her great love of a quarter century, who had died three years earlier and who had once been Maid of Honor to Queen Victoria. She dedicated her final memoir to Woolf.

Virginia Woolf was smitten with Smyth, as one artist with another, smitten with her uncommon “gift for solidifying the connection between [the composer] and the audience,” and tried to procure for her via her Bloomsbury connections the era’s most admired gramophone — the handmade acoustic E.M.G. behemoth, with its enormous papier-mâché horn. Woolf was also smitten with Smyth as a woman, writing to the seventy-three-year-old composer after returning home from a visit with her:

Across the Atlantic, The New York Times did not hesitate to scintillate with reports of Smyth arrested and accused of arson for her activism. While they published no notable reviews of her music, they ran an obtuse review of her memoir under the headline “A Militant Victorian.” In the journalistic equivalent to the posthumous Royal pardon for the gruesome mistreatment of computing pioneer Alan Turing, the paper would make belated reparations a century later.

Still a self-described “half-baked neophyte,” she met Brahms (who dismissed her), Clara Schumann (who inspired her), and Tchaikovsky (who — perhaps because he was raised a proto-feminist and perhaps because he sensed another queer person of talent against an even greater tide of convention — actively encouraged her to find her voice).

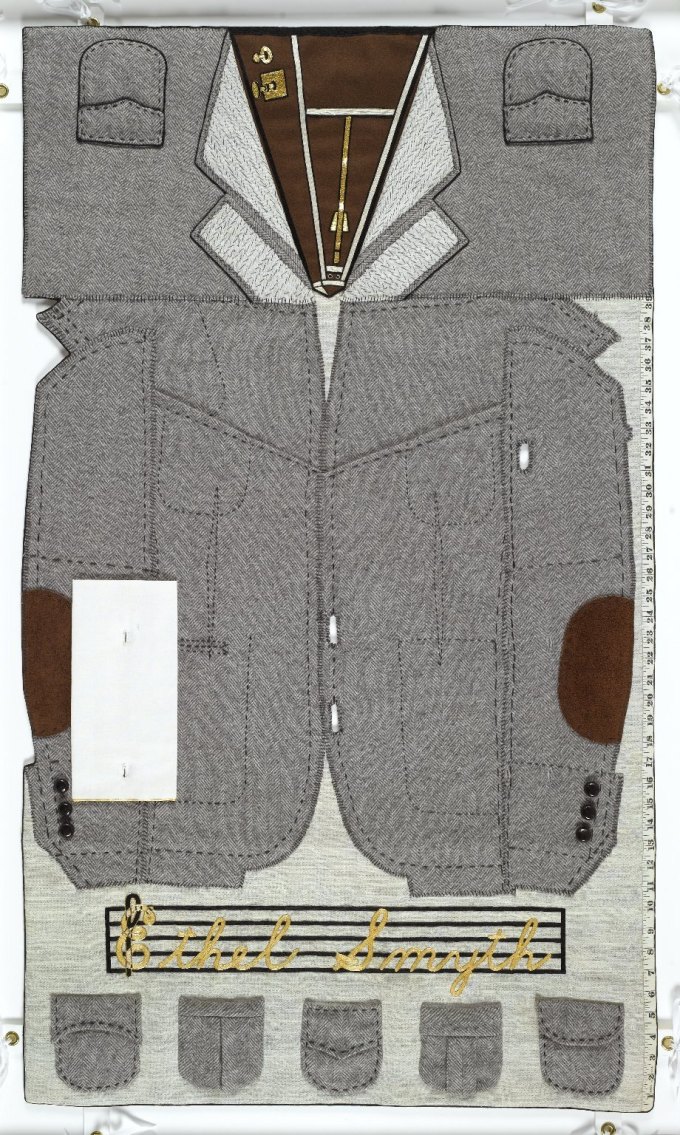

As a young woman, Ethel Smyth (April 22, 1858–May 8, 1944) had weathered her father’s wrath at the clarity with which she saw music as her life and the determination with which she pursued it, animated by one of her musical heroes’ credo that “to live by music, you must live in music.” And so she lived in it and by it, against the tide of her time — bicyclist, mountaineer, golfer, always with a large dog at her side, counterculturally clad in tweed suits and men’s hats, a woman of inconvenient genius and indecorous passions, writing staggering sonatas for violin, symphonies for cello, raptures for orchestra.

I can never tell you how adorable it was of you having me — and letting me feel I shouldn’t wear you out by my deafness. It touched me to the marrow. And I think of all you made possible for me… It made my heart ache to think I am cut off from what is my most overwhelming musical joy — your playing — but I won’t dwell on that. Only don’t think that because I say nothing… well, you know.

Despite her warmhearted confidence and exuberant vitality, Smyth sorrowed at the humiliation of her deafness and was always touched by those who simply treated her as a person and not as a person-sized disability to be set aside from ordinary life and managed. After visiting her friend Violet Gordon-Woodhouse — the visionary keyboard player who became the first person to record and broadcast harpsichord music — Smyth wrote in a letter:

In 1922, Smyth became the first female composer granted damehood. Half a century later, long after her death, she was granted the more substantive honor of a seat at artist Judy Chicago’s iconic Dinner Party project.

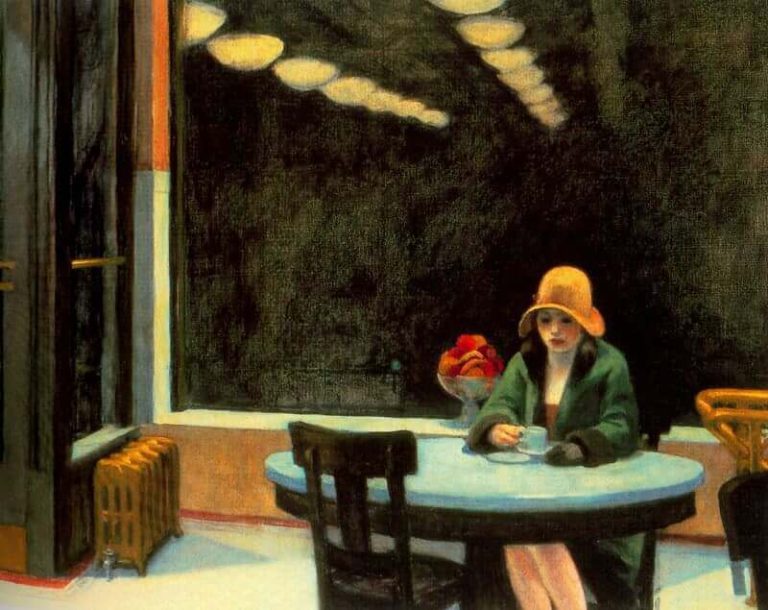

In the last stretch of winter in 1934, a Jubilee Festival celebrated Smyth’s seventy-fifth birthday with two of her most sweeping works — the orchestral masterpiece The Prison and The Mass in D, a choral enchantment — performed at Royal Albert Hall under the benediction of the era’s most influential conductor and music impresario, Thomas Beecham, who had just co-founded the London Philharmonic and who had previously politely snubbed Smyth’s work. It was a bittersweet triumph for her — by then, she was completely deaf, unable to register how the man whose musicianship she so admired, whom the world so admired, was rendering her work.