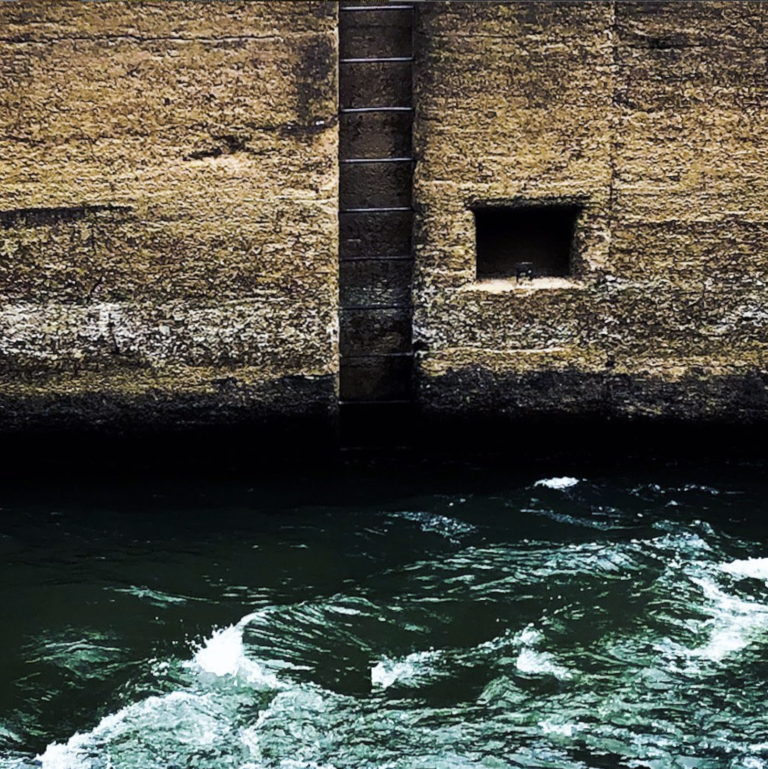

New impressions threaten the security of a world previously built upon the sensations of touch and hearing. Some decide it is better to be blind in their own world than sighted in an alien one… The sober truth remains that vision requires far more than a functioning physical organ. Without an inner light, without a formative visual imagination, we are blind.

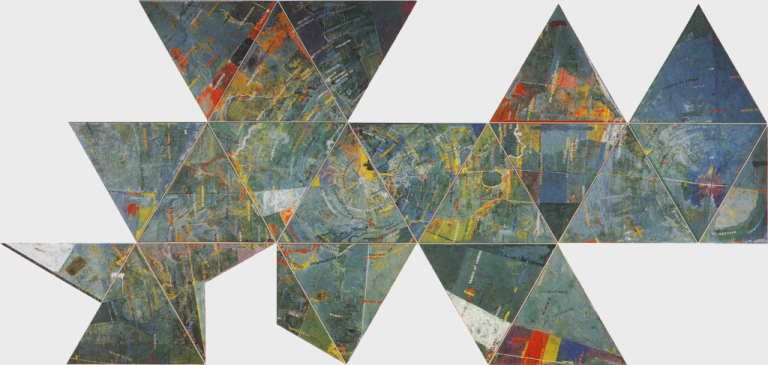

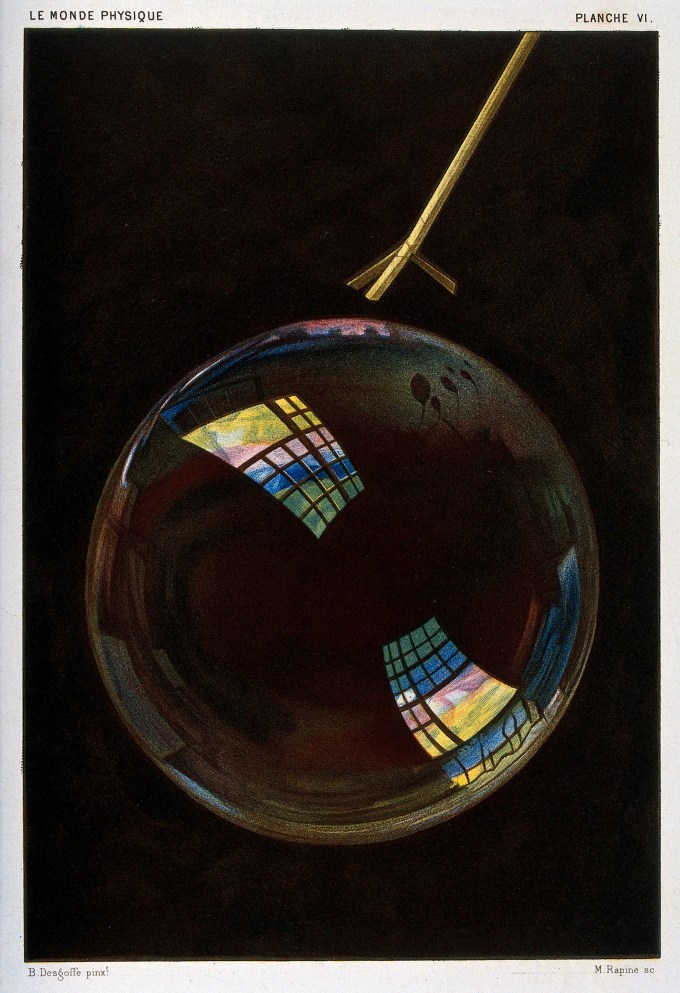

The light of imagination will occupy half of our history, because of its significance for both the ancient world and poetry and the present world and science. No matter how brilliant the day, if we lack the formative, artistic power of imagination, we become blind, both figuratively and literally. We need a light within as well as daylight without for vision: poetic or scientific, sublime or common… The mind is subtly and usually unconsciously active in sight, constantly forming and re-forming the world we see. Thus, we participate in sight.

[…]

Once again peering back into the long tunnel of sensemaking that stretches between particle physics and Plato, Zajonc writes:

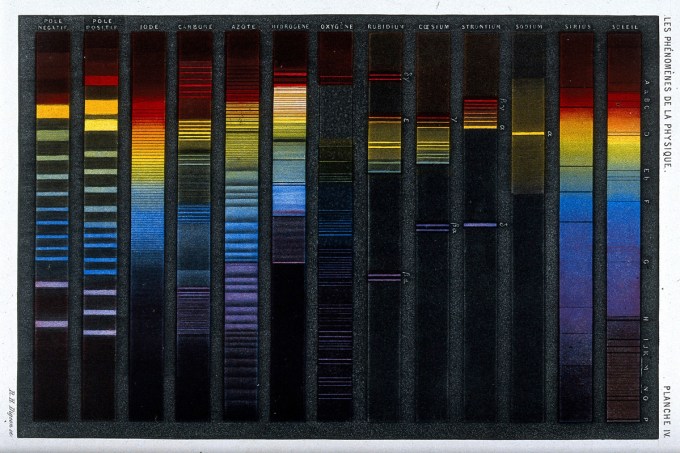

As a young man, Zajonc had fallen under the spell of Goethe’s beautiful but wrong theory of color perception, growing enchanted with the intersection of science and philosophy, of sight and mind — an intersection from which contemporary science has increasingly cowered, hiding behind the blinders of its neo-Cartesian materialism, against which only the rare poetic physicist dares raise a voice of nuanced dissent. Two and a half millennia after Plato correctly deduced the psychological aspect of vision despite his almost comically incorrect theories about its physiology, observing that “the mind’s eye begins to see clearly when the outer eyes grow dim,” Zajonc looks back on the history of our reckonings with the nature of light and insists on the necessary twining of world and mind:

In the remainder of Catching the Light, Zajonc goes on to explore various aspects of the twin histories of light and mind, from anatomy to the aurora borealis, from photography to quantum field theory, from Homer to the Brothers Grimm. Complement it with his magnificent On Being conversation with Krista Tippett, then savor Elson’s “Let There Always Be Light (Searching for Dark Matter),” read by Patti Smith and animated by Ohara Hale for the second installment in the animated season of The Universe in Verse in collaboration with On Being:

As the light of the eye dims, that of the world brightens. As the beacon of the eye gradually retreats, the power of sunlight projects itself deeper and deeper into the human being until finally the ethereal emanations of Plato… vanish from the Western scientific sense of self… Our habits of thought become perceptions, and while powerful and pervasive, these are not universal or “true.”

Besides an outer light and eye, sight requires an “inner light,” one whose luminance complements the familiar outer light and transforms raw sensation into meaningful perception. The light of the mind must flow into and marry with the light of nature to bring forth a world.

[…]

[…]

[…]

[…]

[…]

[…]

[…]

This, to be clear, is not a mystical claim. Several years earlier, the influential theoretical physicist John Archibald Wheeler — who salvaged Einstein’s general relativity from its postwar neglect and popularized the term “black hole” — presented his landmark (and ingeniously titled) It from Bit theory, in which he argued that given the information-based nature of all things physical, “this is a participatory universe [and] observer-participancy gives rise to information.” Months later, the human-warped optics of the Hubble Space Telescope demonstrated this equivalence from the backside, giving us our first glimpse of faraway galactic light from the cosmic horizon of our sight and leaving us gasping at a universe “so brutal and alive it seemed to comprehend us back.”

[…]

In many ways, we act like Moreau’s child. The cognitive capacities we now possess define our world, give it substance and meaning. The prospect of growth is as much a prospect of loss, and threat to security, as a bounty. One must die in order to become. Newly won capacities place us in a tumult of new psychic phenomena, and we become like Odysseus shipwrecked in a stormy sea. Like him we cling tenaciously to the shattered keel of the ship we originally set out upon, our only and last connection to a familiar reality. Why give it up? Do we have the strength to leave, to change? Perhaps the voices encouraging us to venture out on our own belong only to the cruel Sirens? So we close our eyes, and hold on to what we know.