Complement with James Baldwin on what it means to be an artist, then revisit Cather on the life-changing advice that made her a writer and her moving letter to her brother about making art through times of inner turmoil.

A generation before the star teacher of Black Mountain College made her exquisite case for creativity as a way of being, arguing that art is made “with food, with children, with building blocks, with speech, with thoughts, with pigment, with an umbrella, or a wineglass, or a torch,” Cather adds:

Many people seem to think that art is a luxury to be imported and tacked on to life. Art springs out of the very stuff that life is made of. Most of our young authors start to write a story and make a few observations from nature to add local color. The results are invariably false and hollow. Art must spring out of the fullness and the richness of life.

The longer Miss Cather talks, the more one is filled with the conviction that life is a fascinating business and one’s own experience more fascinating than one had ever suspected it of being. Some persons have this gift of infusing their own abundant vitality into the speaker.

Esthetic appreciation begins with the enjoyment of the morning bath. It should include all the activities of life… The farmer’s wife who raises a large family and cooks for them and makes their clothes and keeps house and on the side runs a truck garden and a chicken farm and a canning establishment, and thoroughly enjoys doing it all, and doing it well, contributes more to art than all the culture clubs. Often you find such a woman with all the appreciation of the beautiful bodies of her children, of the order and harmony of her kitchen, of the real creative joy of all her activities, which marks the great artist.

In consonance with Rilke’s beautiful reflections on the reservoir of experiences required for creativity, Cather adds:

Lest we forget, there are infinitely many kinds of beautiful lives.

Cather had honed her own love of life — that essential wellspring of creative vitality — in childhood, roaming the wilderness on foot, on horseback, and in her parents’ farm wagon. As a young writer — not privileged, not straight, not resigned to the era’s conventional domestic destiny for a woman — she often worked until the small hours, ate no breakfast to save time and money, and learned to inhabit the world with the full-body presence that would soon give her novels their uncommonly transportive sensorial enchantment.

The two meandered beneath the fiery autumnal canopy near the home Cather shared with the love of her life, the conversation meandering accordingly in that natural synchrony between the foot and the mind, leaving the interlocutor to marvel:

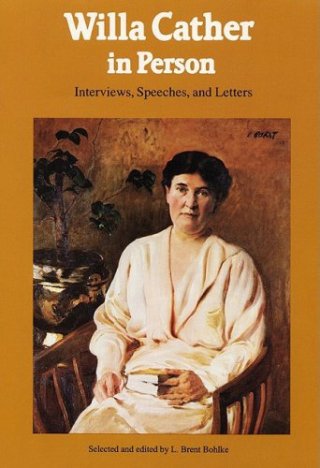

Perhaps because they conversed while walking in the autumn sunshine — something Cather, who found her greatest happiness in nature, had requested — and perhaps because the interviewer was also a woman in an era when so few women’s words and thoughts and experiences appeared on the printed page, the conversation that unfurled, later published in Willa Cather in Person: Interviews, Speeches, and Letters (public library), remains the most candid and revealing glimpse of Cather’s creative credo, process, and philosophy of art — which is at bottom, always, a philosophy of life.

Contemplating the subject of creativity, Cather laments that nothing is more “fatal to the spirit of art” than the rise of what she aptly terms “superficial culture” — the commodification of art not as an instrument of aliveness but as a status symbol, pursued by rich ladies who “run about from one culture club to another studying Italian art out of a textbook and an encyclopedia and believing that they are learning something about it by memorizing a string of facts.” To her, the young black boy on the porch improvising a Verdi opera on his fiddle by ear — with no formal knowledge of what he is playing and no theoretical rationale for why it is so stirring his soul — “has more real understanding of Italian art than these esthetic creatures with a head and a larynx, and no organs that they get any use of, who reel you off the life of Leonardo da Vinci.”

The creative experience, Cather insists, is a matter of tuning into the inner feeling-tone strummed not by our cerebrations but by our creaturely relishment of the world.

Decades before poet and science historian Diane Ackerman rooted our creaturely and creative vitality in the delights of the senses, Cather echoes her contemporary Egon Schiele’s exhortation to “envy those who see beauty in everything in the world” and observes:

Art is a matter of enjoyment through the five senses. Unless you can see the beauty all around you everywhere, and enjoy it, you can never comprehend art.

“Her voice is deep, rich, and full of color; she speaks with her whole body, like a singer… Whatever she does is done with every fibre,” a Nebraskan journalist observed on the pages of the Lincoln Star after meeting the brilliant and reclusive Willa Cather (December 7, 1873–April 24, 1947) while she was working on the novel that would soon win her the Pulitzer Prize, having already written the one that prompted F. Scott Fitzgerald to despair that The Great Gatsby is a failure by comparison.