Nowhere is the joy of existence so apparent as in music… Intelligent life-forms have created a multitude of sounds that express their exhilaration at being alive.

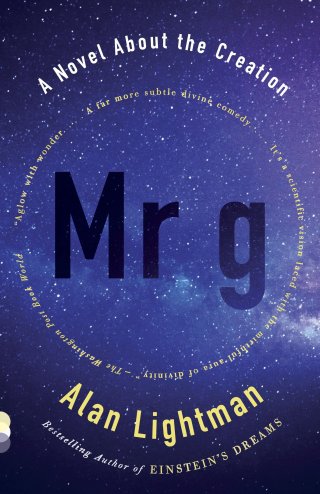

That is what the poetic physicist Alan Lightman explores with great subtlety and splendor throughout his conceptual masterpiece Mr g: A Novel About the Creation (public library), which reads like one long prose poem and which also gave us the transcendent science of what actually happens when you die.

Complement with violinist Natalie Hodges on the poetic science of feeling in sound and composer Caroline Shaw’s transcendent musical inspiriting of classic poetry, then revisit Alan Lightman on time and the antidote to our existential anxiety.

When I sit down at the piano, I enter two different realms: one conscious and one unconscious. The conscious realm is one in which I think about the notes I’m going to play, and the timing and the rhythm and the intensity; and the unconscious is when I just let go and float with the sound. Music is an expression both of the orderly discipline of science and the unfettered flight of the human spirit.

“Matter delights in music, and became Bach,” Ronald Johnson wrote in his stunning 1980 prose poem about music and the mind. This may be why music so moves and rearranges and harmonizes us, why in it we become most fully ourselves — “atoms with consciousness,” axons with feeling. When music courses through us, we are reminded that the mind and the body are one, and that the body — like music, like feeling, like the universe itself — is made of matter and time. It may even be that music is the language of time, mathematics its alphabet; that Margaret Fuller was right when she insisted two centuries ago that “all truth is comprised in music and mathematics”; that, as the cosmologist and jazz saxophonist Stephon Alexander observed in our own century, “it is less about music being scientific and more about the universe being musical.”

At the 2022 Universe in Verse, I invited Alan — a passionate pianist himself — to reflect on the personal and universal power of music and its abiding relationship to physics before reading an excerpt from Robert Johnson’s epic poem:

In every place and in every moment, we were wrapped and engulfed in music. At times, the music poured forth in fierce heaving swells. At other times, it advanced in the softest little steps, delicate as a fleeting veil in the Void. Music clung to our beings as parcels of emptiness had in the past. Music went inside us. I had created music, but now music created; it lifted and remade and formed a completeness of being.

Then there was music. The Void had always vibrated with the music of my thoughts, but before the existence of time the totality of sounds occurred simultaneously, as if a thousand thousand notes were played all at once. Now we could hear one note following another, cascades of sound, arpeggios and glissades. We could hear melodies. We could hear rhythms and metrical phrases gathering up time in lovely folds of sound. Duples and triples and offbeat syncopations. As we moved through the Void [we] were transfixed by the most exquisite sounds, the tender and melodic and rapturous oscillations of the Void.

Through his protagonist — the young creator Mr. g, bored and unsure of himself (“unlimited possibilities bring unlimited indecision”) as he spins a baby universe out of the Void while his aunt and uncle watch on with approving, critical, and sage pronouncements — Alan envisions the realities, as theorized by our current science, of how the universe began, punctuating them with fundaments of our humanity, none more elemental than the soul-resonance of music:

As Mr. g proceeds with his rapturous experiment, most of the music he makes follows a Pythagorean scale, because “chords based on these scales were pleasing to hear,” but he also tinkers with asymmetrical and nonharmonic ratios, which “also produced beautiful music as long as two different notes were not sounded together.” (These, of course, are allusions to the Western and non-Western music traditions.) He writes:

In consonance with philosopher Susanne Langer’s lovely formulation of music as “our myth of the inner life,” he adds: