Bronson Alcott (November 29, 1799–March 4, 1888) — abolitionist, education reformer, women’s rights advocate, early proponent of vegetarianism, philosophical gardener — refined his political and humanistic ideas on the whetstone of fatherhood. He filled notebook after notebook with loving, insightful observations of his four daughters, contemplating the complexities of human nature as he watched them play, ask questions, and piece for themselves the puzzle of being. The title of these notebooks — The Dial — became the title of the epoch-making Transcendentalist journal, on the pages of which America took its infant steps toward original cultural contribution as Ralph Waldo Emerson and Margaret Fuller worked out their confused mutual magnetism while sharing the editorship.

That era dawned on the 29th of November — his own thirty-third birthday — when Louisa May was born. He wrote in his journal:

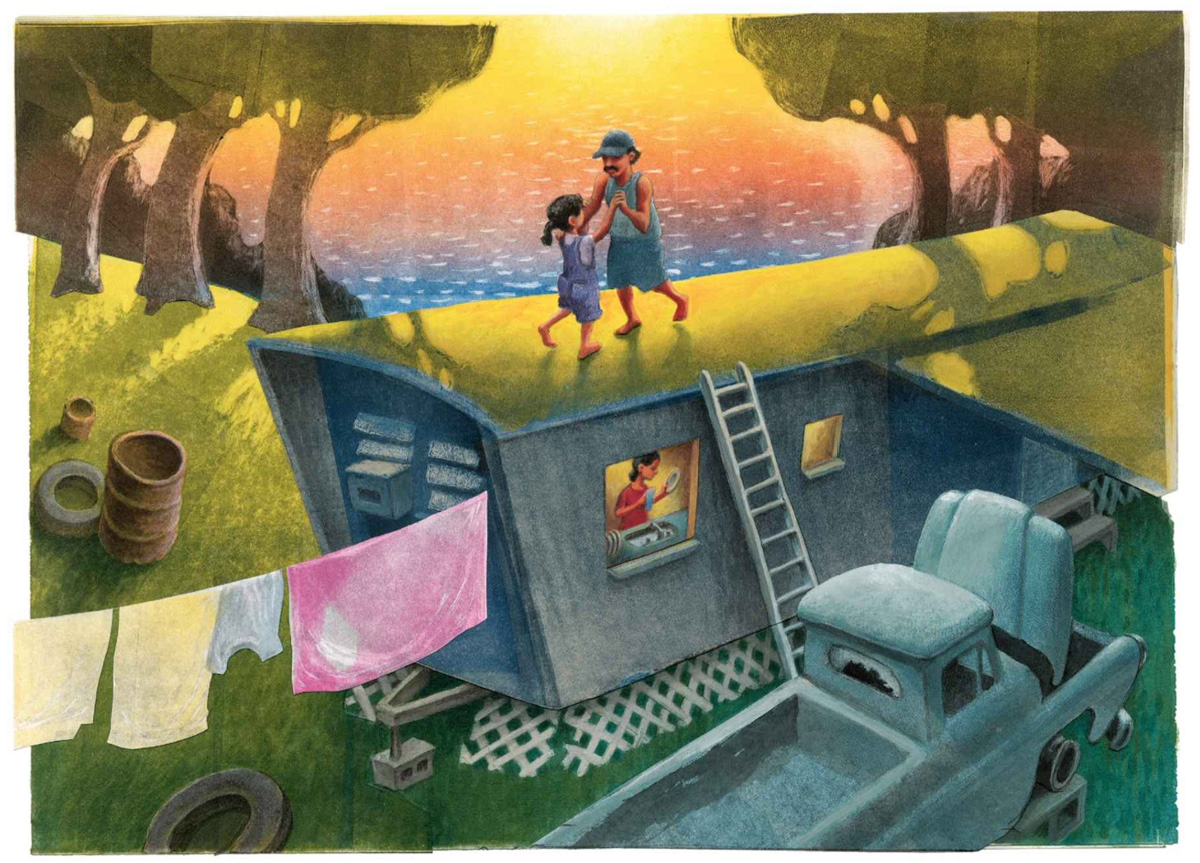

In a passage that sings to those of us who favor a constellation of chosen closenesses over the nuclear family model, Alcott steps beyond the domestic sphere to consider the vivifying rewards of our friendships — those nurturing havens of love in which we best grow and which form, in his lovely phrase, “the Nursery of the Soul”:

Making a family, having a family — these are different things, and different things to different people. But whatever family means to us, in its haven we are in some primal sense making — and remaking — ourselves. It bears remembering that “who we are and who we become depends, in part, on whom we love.”

The birth of his second daughter — who would later turn her formative family experience into one of the most beloved novels of all time — brought a renaissance in Alcott’s entire intellectual, emotional, and spiritual universe. He had just discovered the poetry of Coleridge, in which he found “wisdom not of this earth.” He felt it had done him more good than any writing he had encountered before. He felt it augured a “new era” in his “mental and psychological life” — one in which he was to contemplate ever more deeply the meaning and purpose of our existence.

The human being isolates itself from the supplies of Providence for the happiness and renovation of life, unless those ties which connect it with others are formed. The wants of the Soul become morbid, and all its truth and primal affections are dimmed and perverted. Nature becomes encrusted over with earth and surrounded by monotony and ennui. Few can be happy shut out from the Nursery of the Soul.

Complement with Kahlil Gibran’s poignant advice on parenting and Willa Cather on how our formative family dynamics imprint us, then revisit Alcott on gardening and genius.