Woven into Marletto’s case for counterfactuals is her love letter to science and the art of explanation:

What distinguishes helpful changes in the recipe from unhelpful ones? It is a particular kind of information: information that is capable of keeping itself instantiated in physical systems. It is resilient information.

Leaning on Karl Popper’s famous pillar of sensemaking — “Knowledge consists in the search for truth… It is not the search for certainty.” — she adds:

She turns to the two ways in which nature and human nature generate new knowledge, the generative process we call creativity — “by conjecture and criticism, in the mind; by variation and natural selection, in the wild” — and considers the crucial difference between the two:

This interplay, and how to liberate our search for truth from our craving for certainty, is what Italian physicist Chiara Marletto explores in The Science of Can and Can’t: A Physicist’s Journey through the Land of Counterfactuals (public library) — part field guide to her particular realm of study, part manifesto for the countercultural courage to keep unmasoning the walls of the imaginable and bending the mind beyond the accepted horizons of the possible. What emerges is an impassioned, scrumptiously reasoned insistence that all breakthroughs in science require “as much imagination and perceptiveness as you need to write a good story or a profound poem.”

[…]

Drawing on the example of Neptune and the neutrino — both discovered not by direct observation of the previously unseen planet or particle but by observing curious contradictions in the surrounding system and deducing from them that something in the set of assumptions about what the system is and how it works must be revised. She writes:

In the foreword, Marletto’s collaborator David Deutsch observes that the rate of scientific discovery over the past few centuries has been increasing exponentially, but the discovery of new fundamental truths about nature has stalled and an indolence about attempting new modes of explanation has set in. He writes:

The thinking process, in contrast, can perform jumps… The sequence of ideas leading to a good idea need not consist entirely of good, viable ideas. Nonetheless, knowledge creation in the mind, too, can enter stagnation and stop progressing. We must be wary of not entering such states both as individuals and as societies. Particularly detrimental to knowledge creation are the immutable limitations imposed by dogmas, as they restrain the ability to conjecture and criticise.

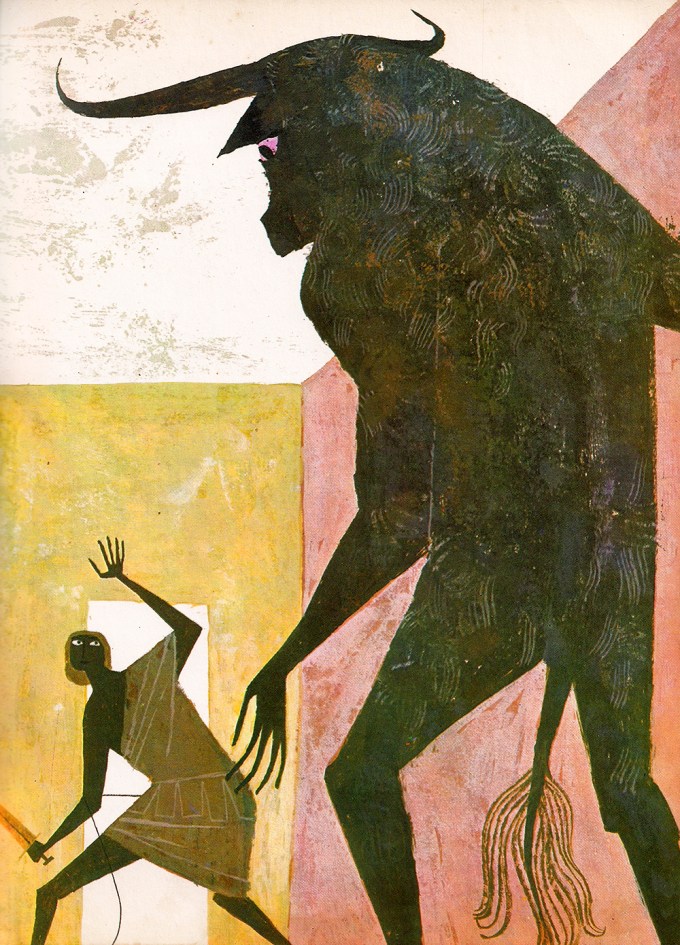

Theseus, son of Aegeus, king of Athens, went to Crete to kill the Minotaur. Theseus made an agreement with his aged father that if he defeated the Minotaur, on their return his crew would raise white sails on the ship; if he perished, they would raise black sails. So off went Theseus, and he defeated the Minotaur. But on his way back, distracted by all sorts of things (including, possibly, the presence of his fiancée, Ariadne, on the ship!), he forgot to tell the crew about the sails. The crew left the black sails on, and Aegeus, who from the highest tower of Athens could see the ship approaching, thought his son was dead. So he threw himself into the sea and drowned. This tragic story is why the sea is now called the Aegean.

“Knowledge” merely denotes a particular kind of information, which has the capacity to perpetuate itself and stay embodied in physical systems — in this case by encoding some facts about the environment… Knowledge is the key to resilience… In fact, knowledge is the most resilient stuff that can exist in our universe.

Natural selection, unlike conjecture and criticism, cannot perform jumps: each of the recipes that leads to a new resilient recipe must itself be resilient — i.e., it must code for a successful variant of a trait of the particular animal in question that permits the animal’s survival for long enough to allow replication of that recipe, via reproduction. But there may be viable, resilient recipes coding for useful traits that can never be realised because they would require a sequence of nonresilient recipes to be realised first, which is impossible, as those recipes produce animals that cannot survive and cannot pass on their genes.

Natural selection, unlike conjecture and criticism, cannot perform jumps: each of the recipes that leads to a new resilient recipe must itself be resilient — i.e., it must code for a successful variant of a trait of the particular animal in question that permits the animal’s survival for long enough to allow replication of that recipe, via reproduction. But there may be viable, resilient recipes coding for useful traits that can never be realised because they would require a sequence of nonresilient recipes to be realised first, which is impossible, as those recipes produce animals that cannot survive and cannot pass on their genes.

Natural selection, unlike conjecture and criticism, cannot perform jumps: each of the recipes that leads to a new resilient recipe must itself be resilient — i.e., it must code for a successful variant of a trait of the particular animal in question that permits the animal’s survival for long enough to allow replication of that recipe, via reproduction. But there may be viable, resilient recipes coding for useful traits that can never be realised because they would require a sequence of nonresilient recipes to be realised first, which is impossible, as those recipes produce animals that cannot survive and cannot pass on their genes.

This task turns out to be impossible: for the story to make sense, and to convey fully its meaning, two attributes of the ship are essential: one, that it can be used to send a signal, by assuming one of two states — white sail showing or black sail showing; the other, that the state of having black or white sails can be copied onto other physical systems — such as Aegeus’s eyes and brain. The copiability property tells us that the flag contains information.

In one of the book’s many charming touches defying the segregation of science from its sensemaking twin — art — she gives an exquisite example of counterfactuals at work in one of humanity’s most abiding masterworks of storytelling and sensemaking: the Ancient Greek myth of Theseus (which also inspired the greatest thought experiment about the nature of the self and what makes you you).

[…]

The traditional conception of physics cannot possibly capture counterfactual properties, because it insists on expressing everything in terms of predictions about what happens in the universe given the initial conditions and the laws of motion only — in terms of trajectories of apples or electrons, forgetting the other levels of explanation. But these other levels of explanation are essential sometimes to grasp the whole of physical reality.

[…]

Now suppose we asked our master storyteller to tell that story with the constraint that he can formulate statements only about what happens — that is, he must report the full story without ever referring to counterfactual properties. In particular, he cannot refer to properties that have to do with what could or could not be done to physical systems.

Complement The Science of Can and Can’t with physicist Alan Lightman’s poetic meditation on what makes our improbable lives worth living between the bookends of possibility, then revisit the story of Alan Turing, the world’s first digital music, and the poetry of the possible.

Marletto writes:

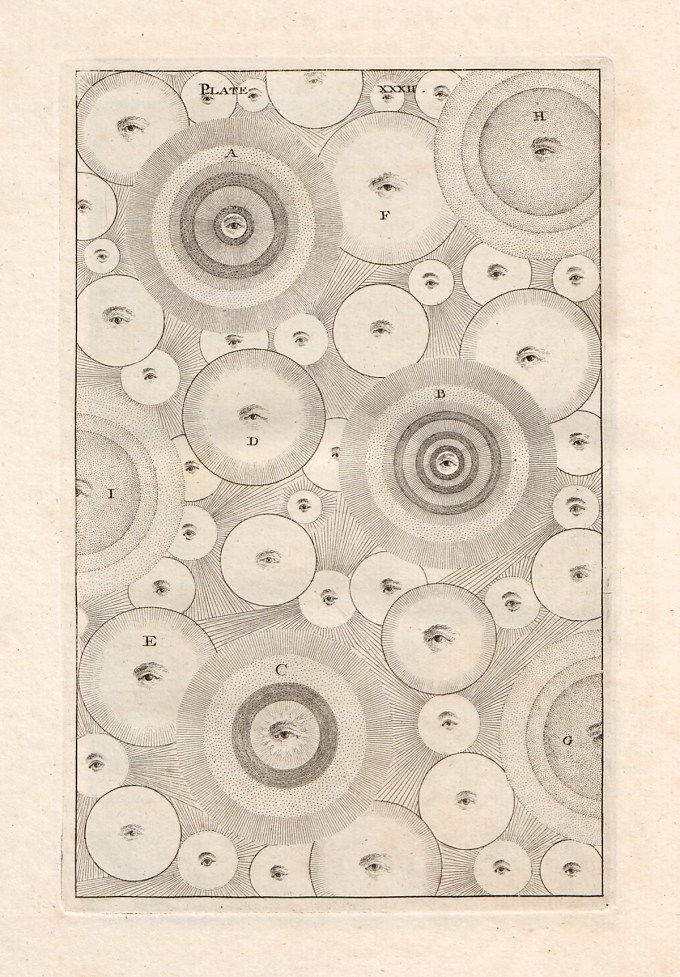

“What we see, we see / and seeing is changing,” Adrienne Rich wrote in her ode to astrophysics. It is changing, however, only when we change the way we look, change our tools for looking, be they physical instruments — the microscope and the telescope, revealing unseen layers of reality — or the instrument of the mind, which devises the microscope and the telescope and the theory. I hear Thoreau bellowing his admonition down the hallway of time as he puzzled over what it takes to see reality unblinded by our preconceptions: “We hear and apprehend only what we already half know.” Marletto writes:

As always happens with contradictions, something in the assumptions has to give.

“Everything that is possible is real,” Bach scribbled in the margins of a symphony three centuries ago, when the existence of other galaxies was unimaginable and hummingbirds were considered magic, when the fact of the atom was yet to trouble the young Emily Dickinson and the fact that it is mutable was yet to splinter the foundation of reality as we understood it.