How to Operate a Lab

Setting up a philosophy lab doesn’t rival the complexity of setting up a STEM lab: no need to purchase 0K of equipment or wrangle with facilities administrators to secure extra space on campus. Still, some initial leg work is necessary. Here are some steps we recommend:

The “lonely-armchair methodology” is one way of approaching philosophy, but it’s not the only way.

Philosophy Labs: Some Recommendations

by Joseph Vukov, Kit Rampala, and Katrina Sifferd

In a recent article in Teaching Philosophy, however, we argue this isn’t the only way to do philosophy well. In fact, we suspect there are myriad ways of doing philosophy well. We focus on one: philosophy labs.

Reasons to Set Up a Lab

[top image: Aleksandr Rodchenko, “Spatial Construction No. 12”]

Philosophers often adhere to what we could call ‘lonely-armchair methodology.’ Sit in your chair; or take a walk; or drink a coffee. Read related work to see what others have said; stew on an idea for a week or a month or a year. Then write it up. Send it off. Desk reject. Stew some more. Revise and resubmit. Stew some more. Accepted. Submit the proofs. Repeat.

Should we completely ditch lonely-armchair methodology in favor of a more collaborative research? Easy answer: no. Moreover, philosophy labs are not for everyone. We believe, however, that the model we have described provides a valuable model for philosophical research and pedagogy, and would welcome broader implementation of it in the field.

In a previous post at Imperfect Cognitions and in our article at Teaching Philosophy, we argued in favor of philosophy labs and explored the model using the framework provided by Positive Interdependence Theory. Here, we take a different tack, and provide concrete recommendations for setting up and operating a philosophy lab, and some reasons you might want to do so.

- Survey campus resources: many campuses offer resources that are easily incorporated into a lab. Each campus is set up differently, but these could include: funding for graduate research assistants, undergraduate research programming, independent studies, and faculty research support. Philosophy labs also provide a solid launchpad for external grant applications, and—if the lab is interdisciplinary—funding streams and administrative support available to more well-heeled departments. Our suggestion: get creative in finding campus resources that might be leveraged to support a lab on your campus.

- Determine the interests and goals of faculty and students: your interests and goals are likely easy to determine. They may include: more meaningful interactions with students, higher-impact research, external support, an expedited timeline for your research program, and so on. The goals of your students may be more variable: admission to law or medical or grad school, a position in top internship, or training in how to become excellent teachers themselves, for example. Philosophy labs, if they are to be genuinely collaborative, must serve the interests and goals of all members. You’d be well served by reflecting on these before setting one up.

- Disaggregate your research process: a well-run STEM lab divides work among its members. A novice undergraduate might get participants’ consent while an advanced undergraduate oversees a simple research protocol. Meanwhile, a graduate student and postdoc might run a statistical analysis, while the faculty PI begins drafting a manuscript. A well-run philosophy lab will resemble a STEM lab in its disaggregated approach to the research process. What steps such a process will include will differ from philosopher to philosopher and from project to project. For some of us, the research process includes translation work, for others, statistical analysis, for still others, time-intensive database research, and for all of us, the careful review of relevant literature and polishing of prose. Faculty will need to take the lead in some of these steps. For other steps, however, a student may be perfectly capable. Setting up a lab requires an initial period of reflecting on your research process and identifying the essential steps. From there, tasks can be divided up and distributed to lab members.

- Identify partner disciplines: philosophy labs need not be interdisciplinary in their goals or membership, but lend themselves well to interdisciplinary scholarship. You would be served well to reflect on which disciplines might be relevant to the interests and goals of you and your students. One of our labs involved faculty from the psychology and criminal justice departments; another brought in faculty from neuroscience and biology. But another still might include history or classics faculty.

That’s a tried and true model of doing philosophy. And it is a model that we follow a lot of the time. We’re fans of lonely-armchair methodology, and we see no reason to abandon it.

- Ask students to apply: in our labs, we have found that a formal application process is crucial. Submitting an application selects for the most interested students, gives you a snapshot of a student’s background and skill sets, and gives the application more professional heft. Some campuses have infrastructure for a formal application process for student research, though we have found a less formal cover letter and CV submission to be sufficient.

- Hold regular meetings: our colleagues in STEM fields often hold weekly lab meetings. Weekly meetings may not be necessary. But regular lab meetings are essential to moving projects forward. And Zoom provides a convenient platform for members who are studying abroad or away for the summer.

- Assign tasks: you’ve disaggregated your research process, right? The next step is the painful one: assigning tasks you would have carried out yourself to capable students. Not all the tasks: that would be inappropriate, leave students in over their heads, and remove you from your own research. We have found, however, that students are fully capable of accomplishing large parts of the research process. At the same time, students may also pursue research-related projects of their own and get feedback from the lab group.

- Pursue concrete goals: one thing that makes a philosophy lab differ from a directed reading or independent study is its pursuit of concrete, professional goals, such as published commentaries or book reviews, funded scholarships, or the development of an article manuscript. What those goals are will differ from lab to lab, but without them, the lab loses the primary ends towards which it should be striving.

Prep Work

- A pedagogically-rich experience for students: as teachers, we pursue moments in which students own the pursuit of philosophical questions for themselves. Philosophy labs don’t guarantee those kinds of experiences, but in our work with labs, we have observed them with greater frequency. We also believe philosophy labs are based on best pedagogical practices, and refer you to our article in Teaching Philosophy for the argument.

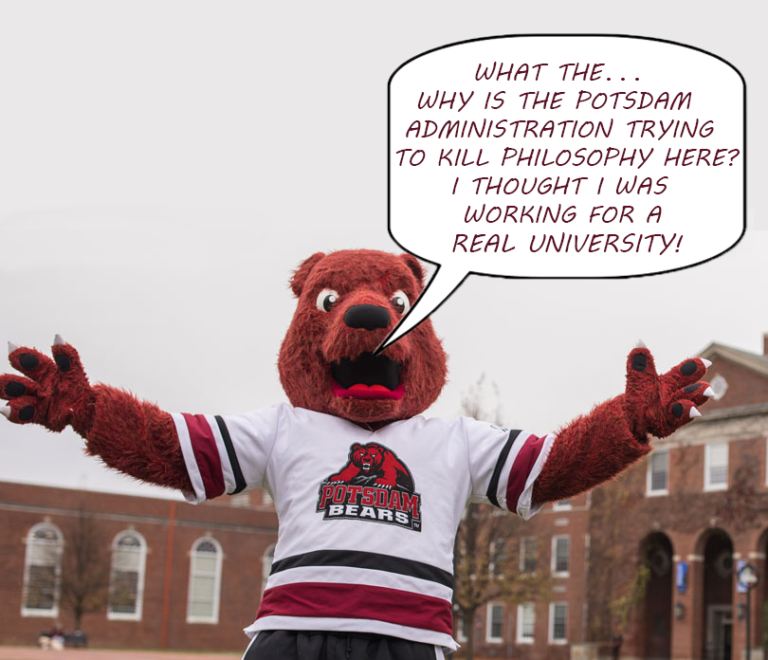

- Attract students to philosophy: if you are like us, you regularly bemoan the relatively low number of philosophy majors at your school. We all would like to see more philosophy majors, both for the intrinsic goods that philosophy confers and also to help make our annual requests to the dean a little more convincing. But there’s a stumbling block to wooing majors away from rival departments. Other departments provide students with concrete opportunities as part of departmental life: biology students can work in a lab; business majors can pursue an internship; education majors can teach at local high schools. Philosophy majors are more rarely granted these kinds of opportunities. Philosophy labs provide one concrete opportunity for philosophy majors to pursue (no doubt there are others as well), and thus another reason to choose the major.

- Increased research productivity: allow us to describe one way a well-run lab might look. You, as the faculty PI, identify a potentially interesting research project and a tentative thesis. You assign some undergraduates to background reading. Two weeks later, they share a well-annotated bibliography. You read through it, and learn quite a bit. You hone the direction of the research. From there, a graduate student begins developing a manuscript. The draft hits a hiccup. You step in, and move the process forward. The grad student finishes the draft. You then hone it into something more polished. The entire lab then reads through the draft, and an undergraduate identifies an important objection. You work it into the manuscript, along with a reply (formulated by the graduate student). The manuscript is finished. You submit. It is as good (or better) as something you would have developed on your own, and you were able to get it under review in half the time it would typically take. Generally, we have found that philosophy labs increase research productivity, without loss in research quality.

- Running a philosophy lab is a blast. Lonely-armchair methodology works but can be, well… lonely. Philosophy labs are many things, but they are definitely not lonely. If they are run well, and if you’ve selected excellent students, philosophy labs provide a meaningful experience for both faculty and students who are involved. Think of the best conversations you’ve had in the philosophy lounge. Then, make those conversations regular and add in the possibility of publishing the results, and you get a picture of what working in a philosophy lab can look like.

Philosophy labs are modeled on labs in STEM fields. No, philosophy labs typically won’t need a budget for beakers or Bunsen burners. Rather, philosophy labs follow the model provided by STEM labs in bringing together researchers at various stages of development—faculty, graduate students, and undergraduate students—to work collaboratively on professional-level projects. Philosophy labs are not merely independent studies or reading groups or research assistantships. They are instead research teams that include students and aim at professional goals: publications, fellowships, grant support, etc. Experimental philosophers have been using a lab-based model for years. We believe it is more broadly applicable within the discipline.

In this guest post*, Joseph Vukov (Loyola University Chicago), Kit Rempala (Loyola University Chicago), and Katrina Sifferd (Elmhurst University) discuss an alternative, the philosophy lab, which they recently wrote about in their article, “Philosophy Labs: Bringing Pedagogy and Research Together,” in Teaching Philosophy. (You can follow the authors on Twitter: @JosephVukov, @The_Kit_Effect, and @Ksifferd.)