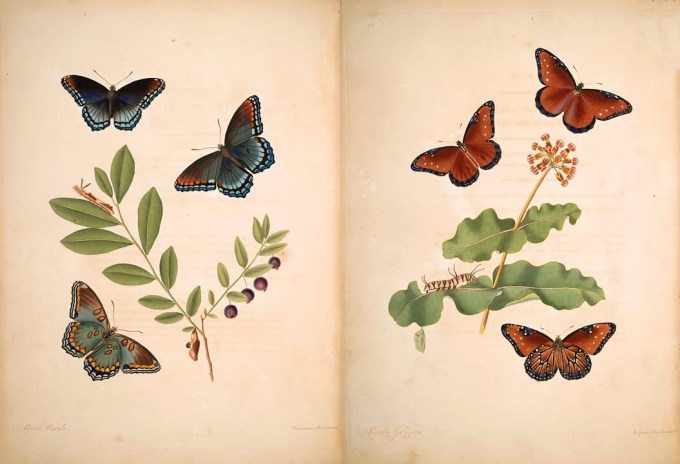

My favorite of his drawings, both aesthetically and scientifically, are the several species of hawk-moth, Sphingidae — the unsung heroes of the pollinator world.

By the end of his long life, more than double the era’s life expectancy, he had produced thousands upon thousands of illustrations of insects, including the native plants they live on and pollinate into life, and several sets of birds. Today, his work is celebrated as some of the finest pictorial scholarship in the history of science and some of the finest scientific illustration in the history of art, held and exhibited in natural history and art museums all over the world. The best of it is collected in Abbot’s magnum opus. The Natural History of the Rarer Lepidopterous Insects of Georgia (public library), originally published in 1797.

As the air grew flammable with the spirit of revolution, he considered returning to London, considered following in Merian’s footsteps and voyaging to the butterfly paradise of Surinam, but ultimately decided not to give up on America just yet.

His first two shipments were lost at sea. Still, he persisted.

Complement with Stephen Jay Gould on what Nabokov’s butterfly studies reveal about the nature of human creativity and the fascinating natural history of how early pollinators gave Earth its colors, then revisit other stunning art from the golden age of natural history illustration: stunning snails from the world’s first pictorial encyclopedia of mollusks, psychedelic fishes from the world’s first marine life encyclopedia in color, the vibrant life-forms of the Great Barrier Reef from the first study of one of Earth’s most delicate ecosystems, and the otherworldly beauty of jellyfish rendered by the artist-scientist who coined the word ecology.

As the months unspooled into years, he went on drawing. He served in the British army during the Revolutionary War and went on drawing, got married, had a son, and went on drawing, lost his wife and went on drawing, with a particular passion for the rarest and most neglected of species.

And so, in the summer of his twenty-third year, John Abbot made the arduous Atlantic crossing, heading for the capital settlement of the first British colony in North America: Jamestown, Virginia.

They are the hummingbirds of the insect universe, with majestic bodies up to eightfold the weight of the average half-gram butterfly and a mighty flight-motor reaching up to 60 wingbeats per second. With tongues up to three times the length of their bodies, they pollinate some of Earth’s most fragrant blooming plants — jasmine, gardenia, honeysuckle, wild rose, evening primrose.

In the harsh winter of 1775, he traveled to Georgia to stay with a family he had befriended during the transatlantic crossing — the Goodalls (possible kin of Jane Goodall). Living in a log cabin 100 miles outside Augusta, Abbot immersed himself in the world of insects and birds, studying and painting the dazzling diversity of winged life.

John was still a teenager when the Old World’s most venerated scientific institution, The Royal Society of his native London, took notice of his consummate entomological illustrations. While his trailblazing compatriot Sarah Stone was drawing the exotic animals of Australia and New Zealand, he was encouraged to leave for North America to help shed light on the insect corner of the continent’s largely unexplored living landscape.

From the moment he set foot on American soil, throughout those difficult early years as a young immigrant, throughout the scientific disenchantment with a habitat far less biodiverse than he had expected, he persisted in collecting and rearing insects, studying and drawing them to send his painstaking artwork back to London.

A century after the self-taught German naturalist and artist Maria Merian laid the foundation of entomology with her art, and a century before the Australian teenage sisters Harriet and Helena Scott fomented one of the greatest triumphs of conservation with their stunning butterfly drawings, John Abbot (1751–1841) became the first artist and naturalist to document pictorially the wing-borne beauty of the New World.