James writes:

If we are not careful enough with the momentum of our own minds, we can live out our days in this expectant near-life existence.

It matters not at all whether we are holding our breath for a triumph or bracing for a tragedy. For as long as we are waiting, we are not living.

Complement with Anaïs Nin on how reading awakens us from the trance of near-living and Mary Oliver on the key to living with maximum aliveness, then revisit Henry James’s equally brilliant sister Alice on how to live fully while dying.

When the protagonist meets a woman to whom his entire being pulls him, he begins spending time with her but ultimately keeps her heart at arm’s length, too afraid to love her, telling himself that he is protecting her from his fatalistic fate, failing to recognize that love itself is that great force of self-annihilation and transformation, “rare and strange” even as the most commonplace human experience.

It is, of course, a dramatized caricature of our common curse — the treacherous “if only” mind that haunts all of us, in one way or another, to some degree or other, as we go through life expecting the next moment to contain what this one does not and, in granting us some mythic missing piece that forever keeps us from the warm glad feeling of enoughness, to render our lives worthy of having been lived.

The wanting starts out innocently — awaiting the birthday, the new bicycle, Christmas morning; awaiting the school year to end, or to begin. Soon, we are awaiting the big break, the great love, the day we finally find ourselves — awaiting something or someone to deliver us from the tedium of life-as-it-is, into some other and more dazzling realm of life-as-it-could-be, all the while vacating the only sanctuary from the storm of uncertainty raging outside the frosted windows of the here and now.

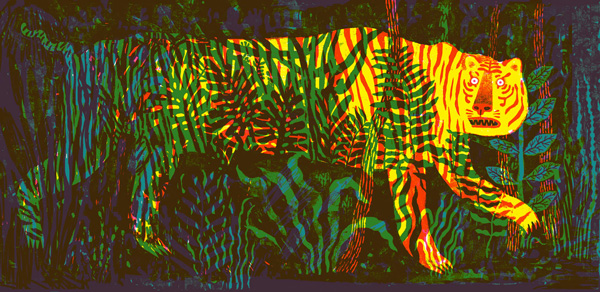

That is what Henry James (April 13, 1843–February 28, 1916) explores in his 1903 novella The Beast in the Jungle, found in his collection The Better Sort (public library | public domain) — the story of a man whose entire life, from his earliest memory, has been animated by “the sense of being kept for something rare and strange, possibly prodigious and terrible,” something fated “sooner or later to happen” and, in happening, to either destroy him or remake his life. He calls it “the thing,” imagines it as a “beast in the jungle” lying in wait for him, and spends his life lying in wait for it, withholding his participation in the very experiences that might have that transformative effect — leaping after some great dream, risking his life for some great cause, falling in love.

When Time forecloses possibility, as Time always ultimately does, he arrives at his final reckoning at her tombstone:

“The things we want are transformative, and we don’t know or only think we know what is on the other side of that transformation,” Rebecca Solnit wrote in her exquisite Field Guide to Getting Lost.

The escape would have been to love her; then, then he would have lived. She had lived — who could say now with what passion? — since she had loved him for himself… The Beast had lurked indeed, and the Beast, at its hour, had sprung; it had sprung in that twilight of the cold April when, pale, ill, wasted, but all beautiful, and perhaps even then recoverable, she had risen from her chair to stand before him and let him imaginably guess. It had sprung as he didn’t guess; it had sprung as she hopelessly turned from him, and the mark, by the time he left her, had fallen where it was to fall. He had justified his fear and achieved his fate; he had failed, with the last exactitude, of all he was to fail of; and a moan now rose to his lips… This was knowledge, knowledge under the breath of which the very tears in his eyes seemed to freeze. Through them, none the less, he tried to fix it and hold it; he kept it there before him so that he might feel the pain. That at least, belated and bitter, had something of the taste of life. But the bitterness suddenly sickened him, and it was as if, horribly, he saw, in the truth, in the cruelty of his image, what had been appointed and done. He saw the Jungle of his life and saw the lurking Beast; then, while he looked, perceived it, as by a stir of the air, rise, huge and hideous, for the leap that was to settle him. His eyes darkened — it was close; and, instinctively turning, in his hallucination, to avoid it, he flung himself, face down, on the tomb.

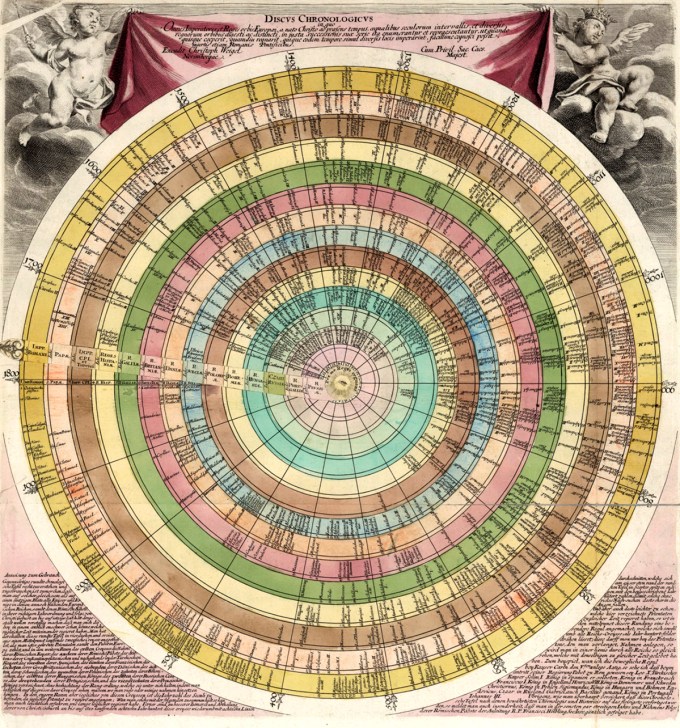

Since it was in Time that he was to have met his fate, so it was in Time that his fate was to have acted; and as he waked up to the sense of no longer being young, which was exactly the sense of being stale, just as that, in turn, was the sense of being weak, he waked up to another matter beside. It all hung together; they were subject, he and the great vagueness, to an equal and indivisible law. When the possibilities themselves had accordingly turned stale, when the secret of the gods had grown faint, had perhaps even quite evaporated, that, and that only, was failure. It wouldn’t have been failure to be bankrupt, dishonoured, pilloried, hanged; it was failure not to be anything.