“I am always your debtor,” he wrote to the artist.

Here was a tall gaunt man who looked like a priest and carried himself like a professor, neat and precise, Victorian to the bone, wresting from his unquiet mind something of such wildness and such defiant beauty that one is staggered into remembering that consciousness abides no exteriors.

Upon seeing Rackham’s illustrations, Barrie found himself “entranced.”

Complement with Rackham’s illustrations for The Tempest and Irish fairy tales, then revisit the tragic teenage prodigy Virginia Frances Sterrett’s tender and haunting illustrations for old French fairy tales.

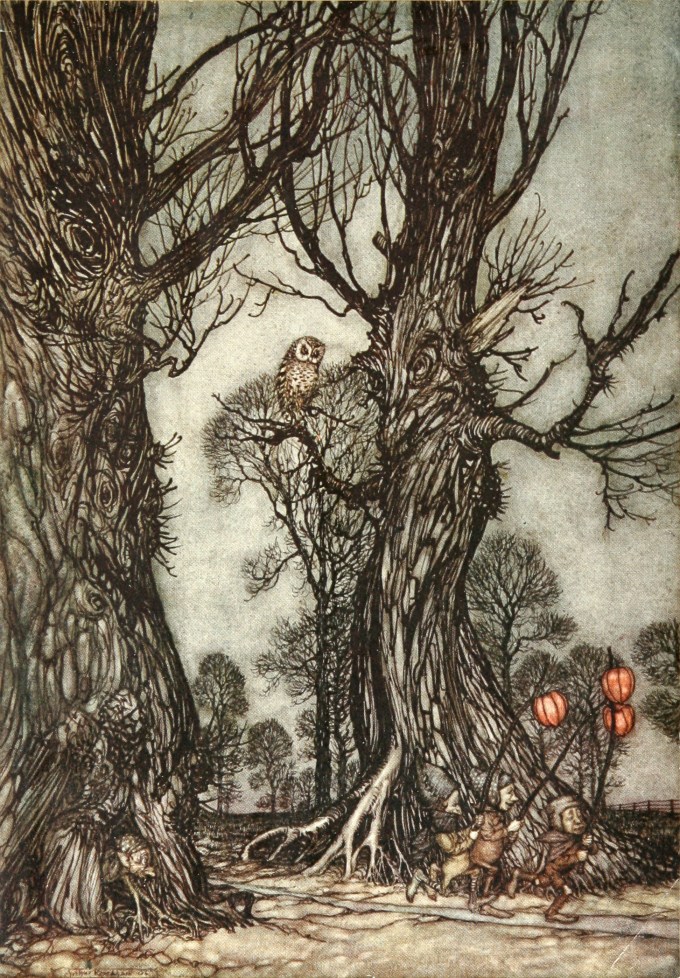

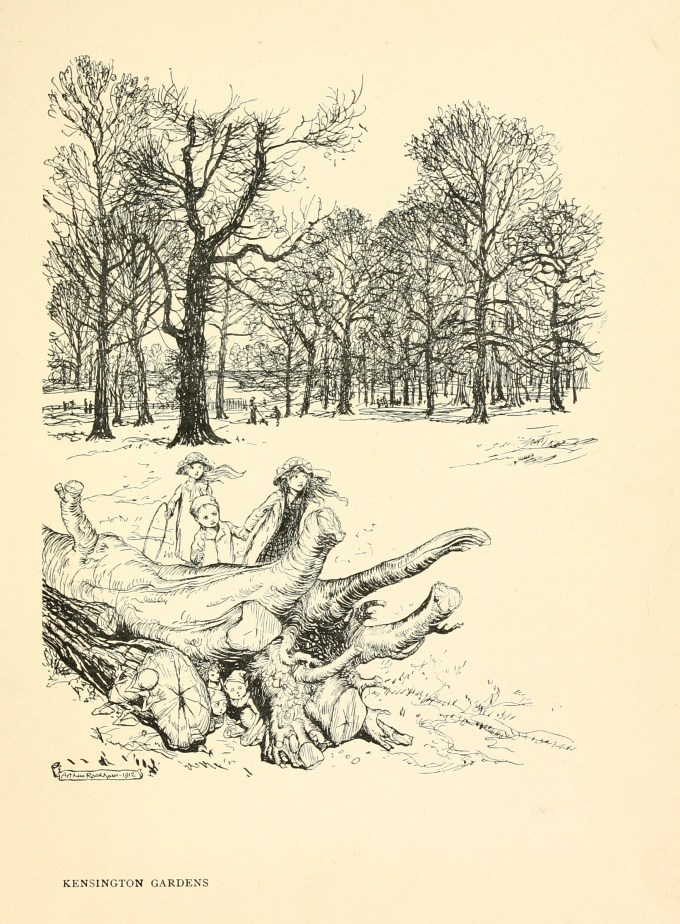

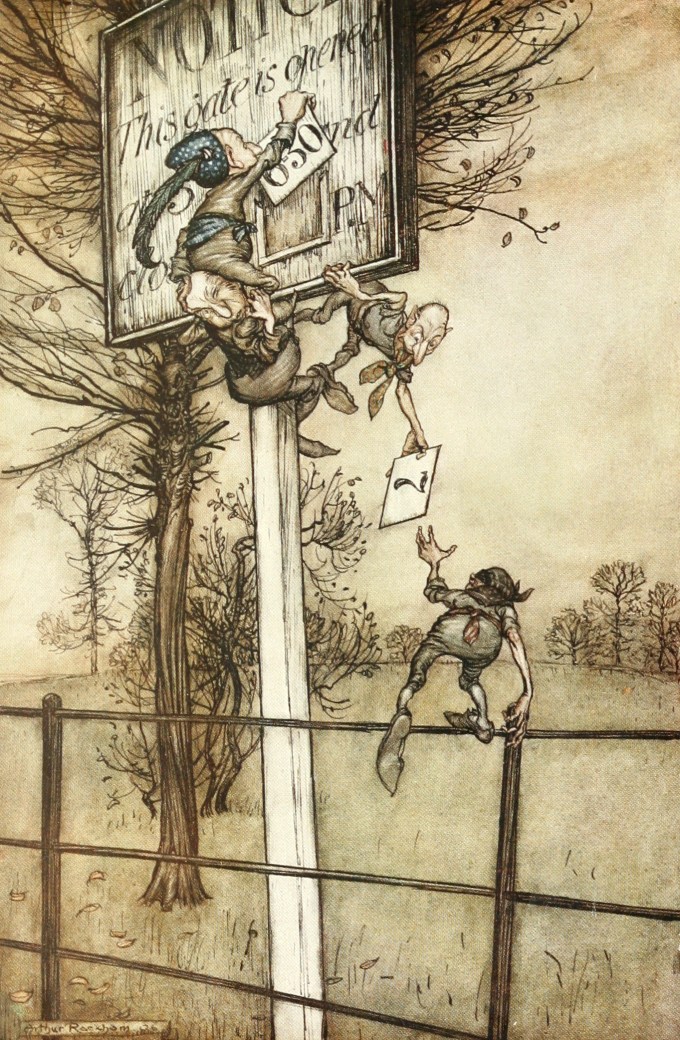

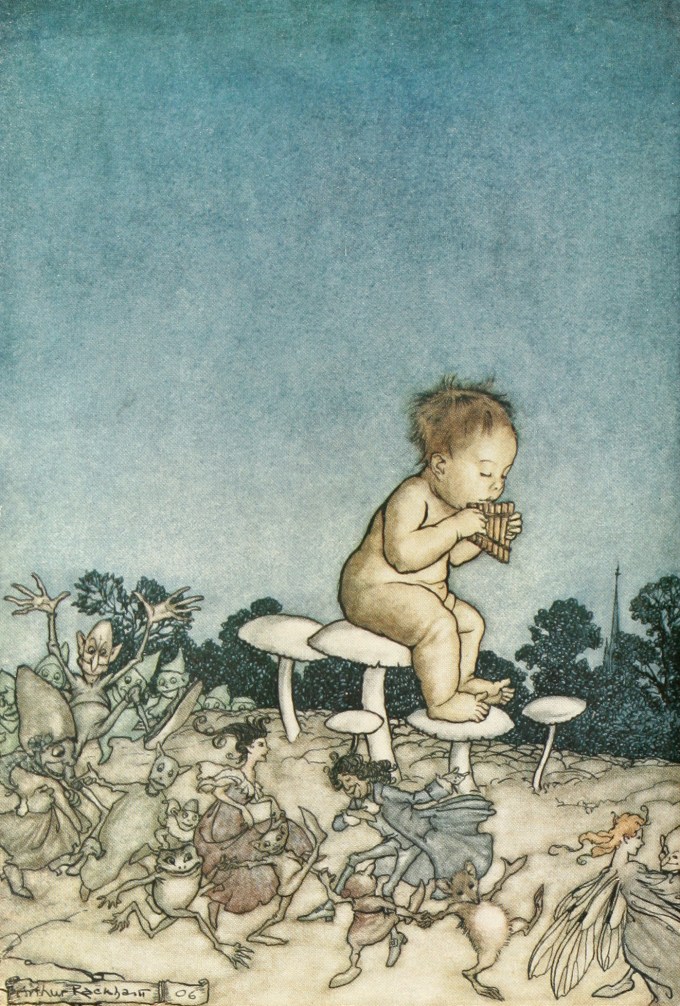

Four years later, six of its chapters sprouted a new book, not for adults but for actual children. J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens (public library | public domain) — the story of baby Peter, who, “like all infants,” was part bird but has now to learn to live an earthbound life — was published in 1906 with illustrations by the wildly imaginative, wildly prolific Arthur Rackham (September 19, 1867–September 6, 1939).

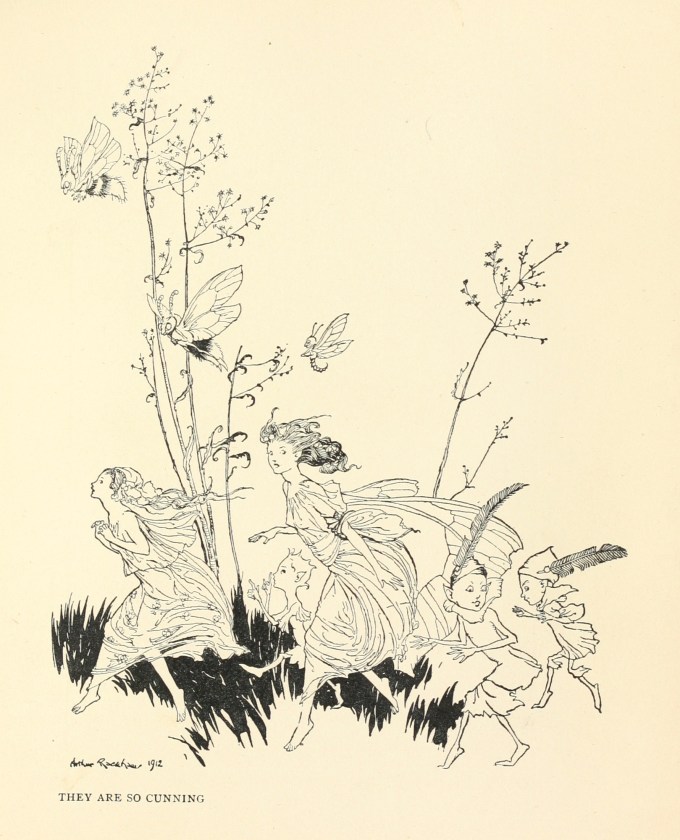

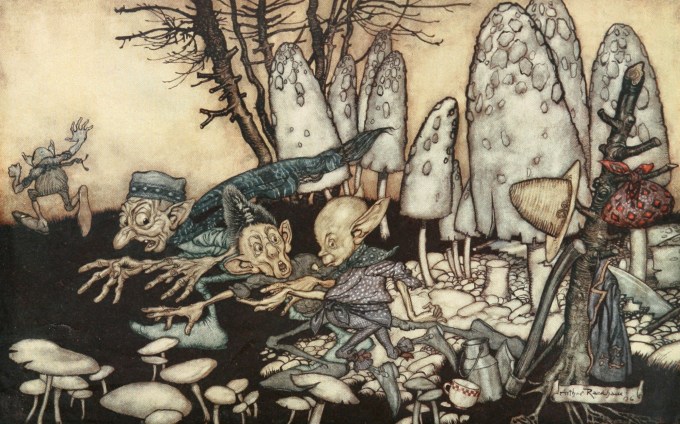

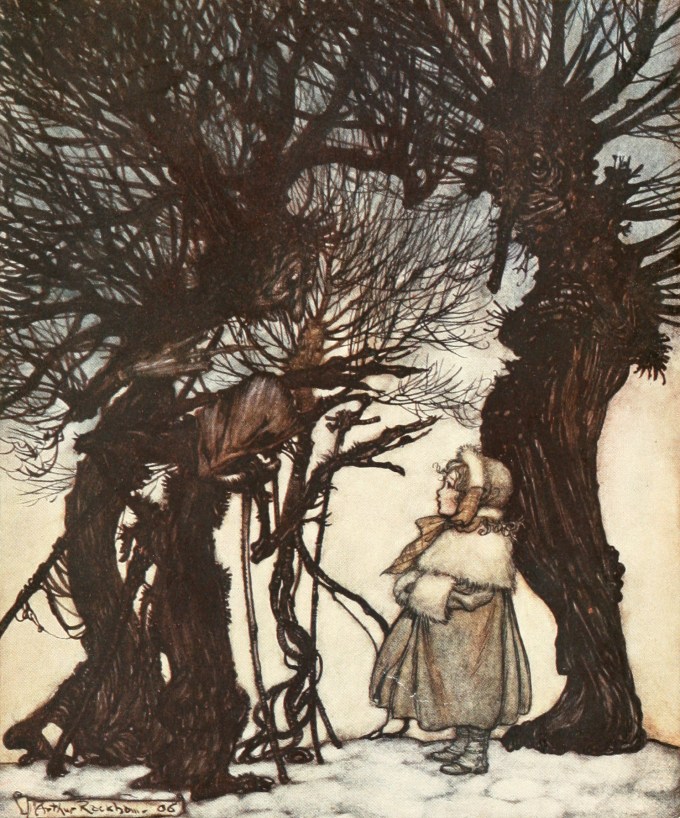

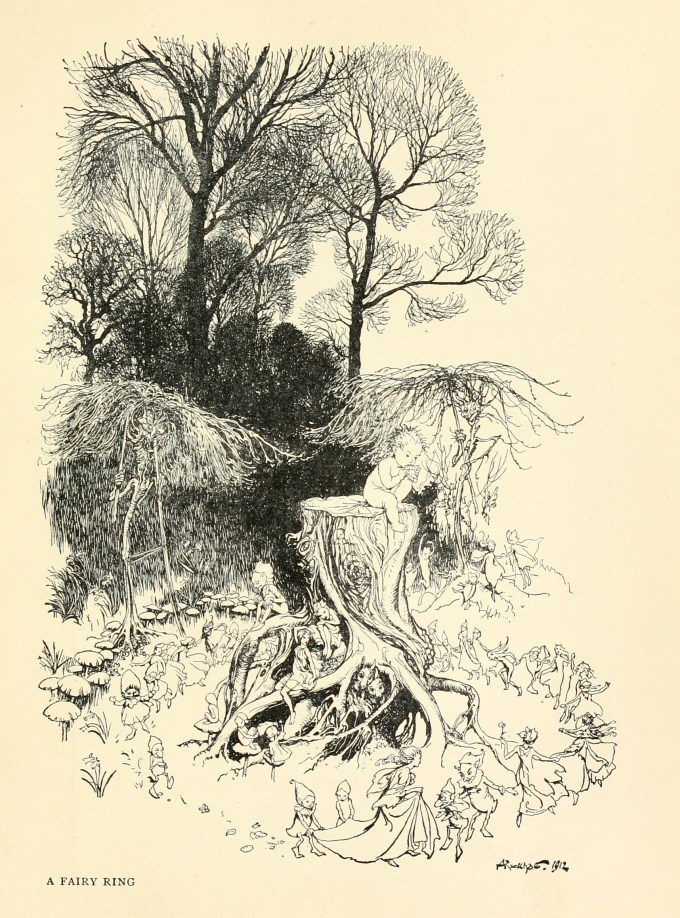

“I regret that the chance has been let slip of permanently peopling Kensington Gardens as the book might have done it,” Rackham rued of the rise of the second Peter, overlooking the fact that it was the first, as rendered in his own enchanted art, from which the second had sprung, both in the public’s imagination and in the author’s. Without Rackham’s fairies, there might be no Wendy; without Rackham’s Queen Mab, there might not be half of Disney.

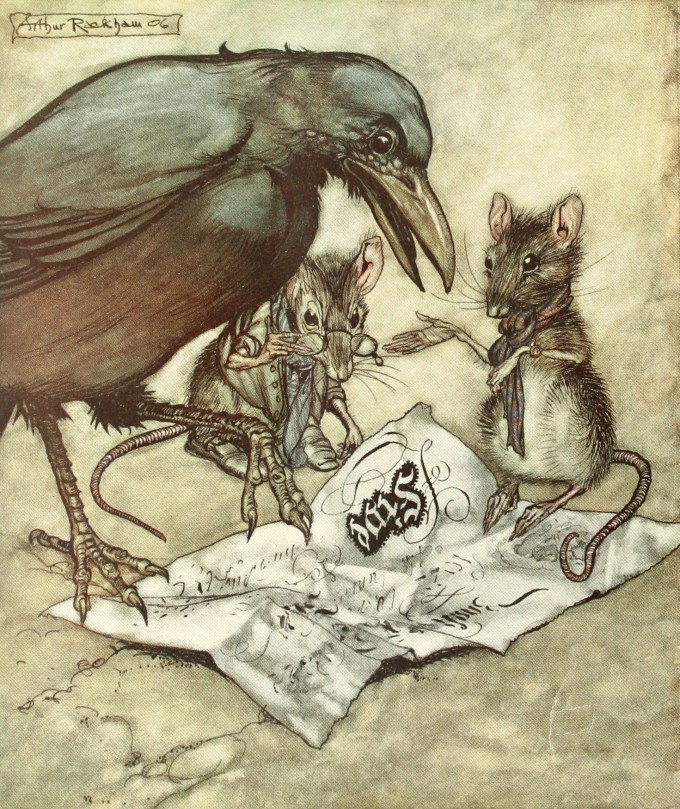

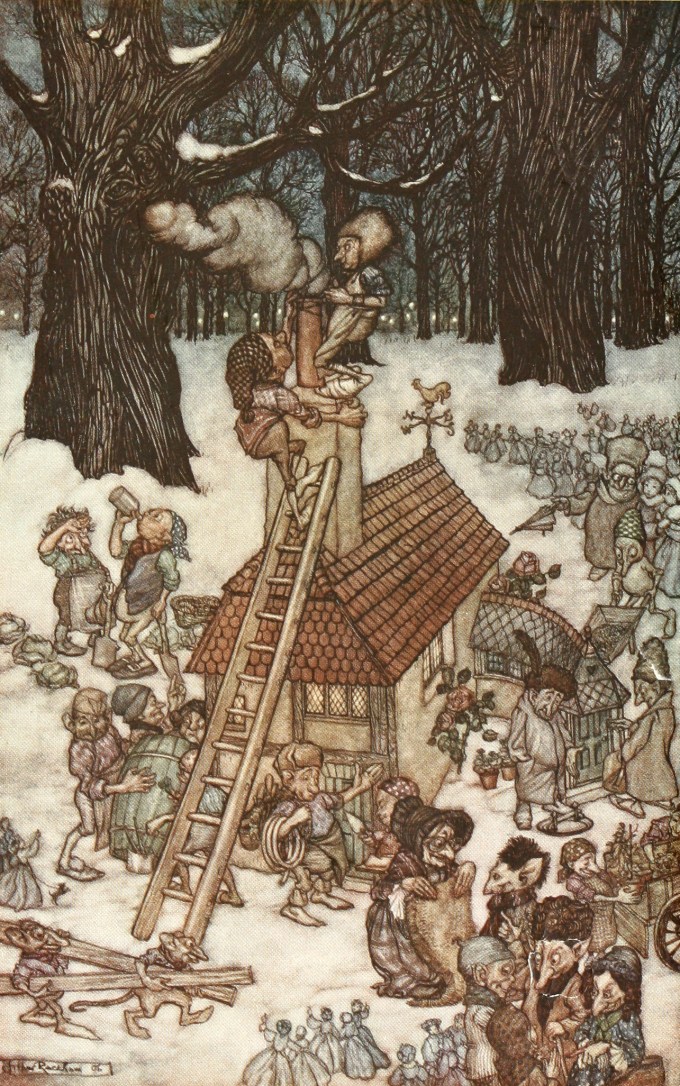

A year later, Rackham would revolutionize the technology and economics of book art with his Alice in Wonderland illustrations; Peter Pan became the R&D lab for his revolution, working within the limitations of the three-color printing process then available to create worlds of wonder with his meticulous ink lines, populating London’s familiar landscapes and places with otherworldly creatures of haunting tenderness and strangeness — Shakespearean fairies and talking mice and, of course, his signature enchanted trees.

In the first years of the twentieth century, a strange book titled The Little White Bird, or Adventures in Kensington Gardens enchanted readers with its fusion of whimsy and dark humor, its way of addressing adults in a way that honors the eternal child alive in each of us, and especially with one of its characters: a small boy named Peter Pan.

Rackham, for his part, felt betrayed by Barrie in the land of the imagination, faulting the author for creating two entirely different Peter Pans — the baby of Kensington gardens and the eternal child of Never-Never Land, which he felt had “entirely eclipsed” the first Peter despite Never-Never Land being a “poor prosy substitute” for the original world.