Out of the totality arises a larger sense of reckoning — a person of uncommon soulfulness and sensitivity to the subterranean strata of life, approaching the end of his days with a cascade of curiosity, singing the ultimate question: What is all this?

Often, our deepest questions are our simplest ones, and our wildest questions — the most maddeningly unanswerable ones — are our most resaning, most redolent with meaning. This is why children’s questions are so often portals to the profoundest answers.

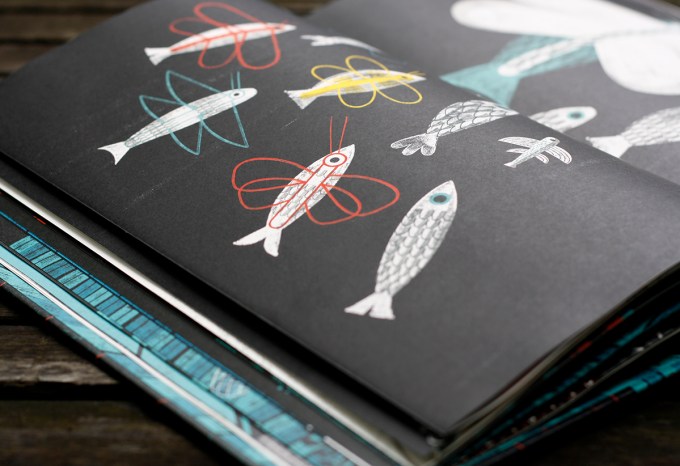

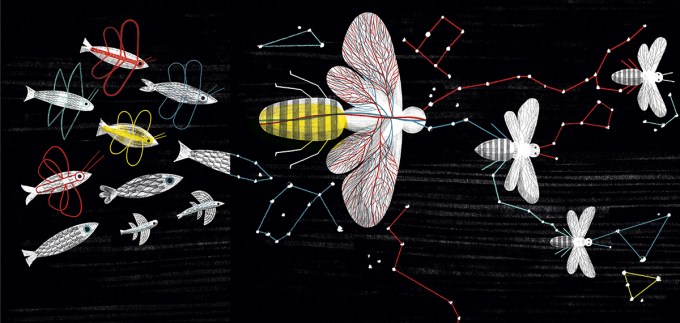

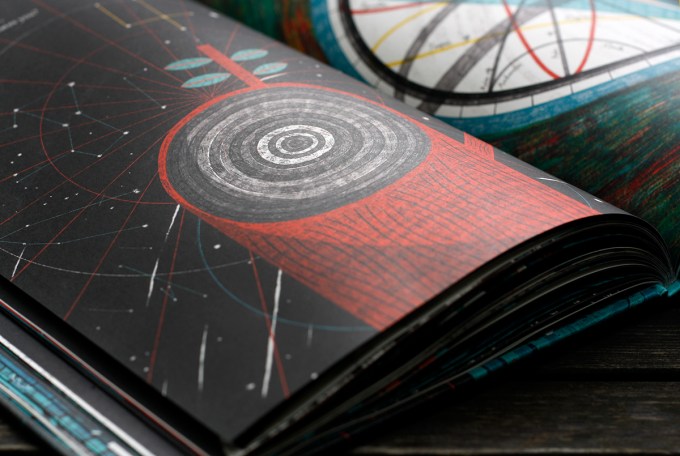

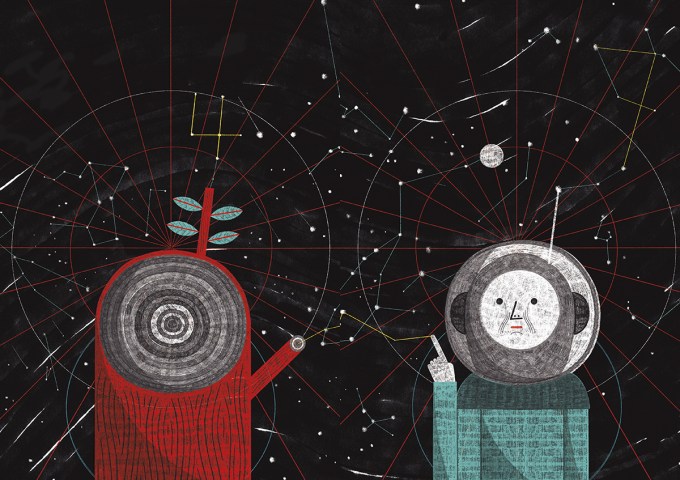

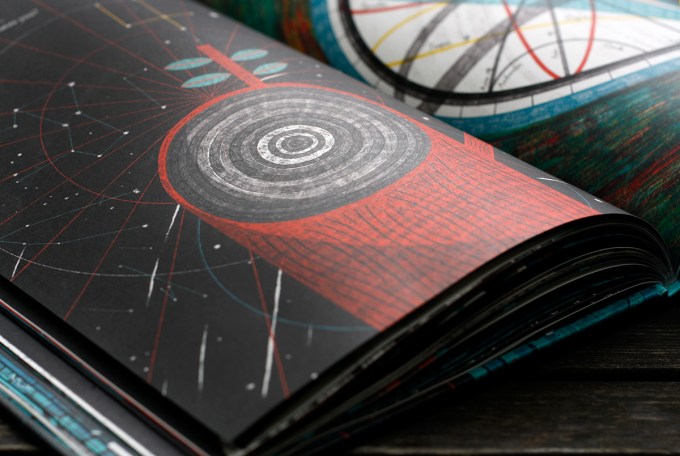

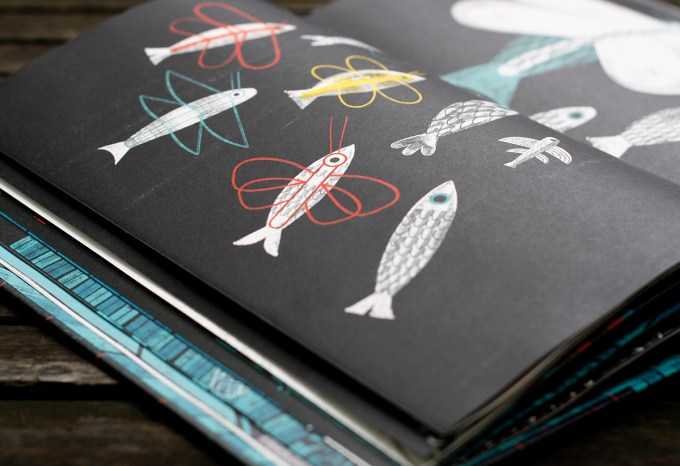

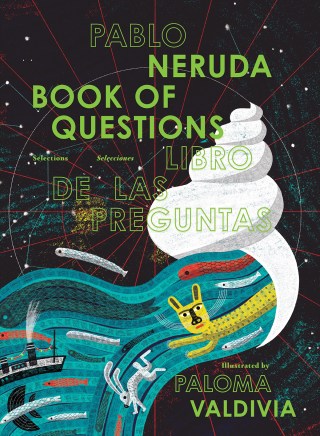

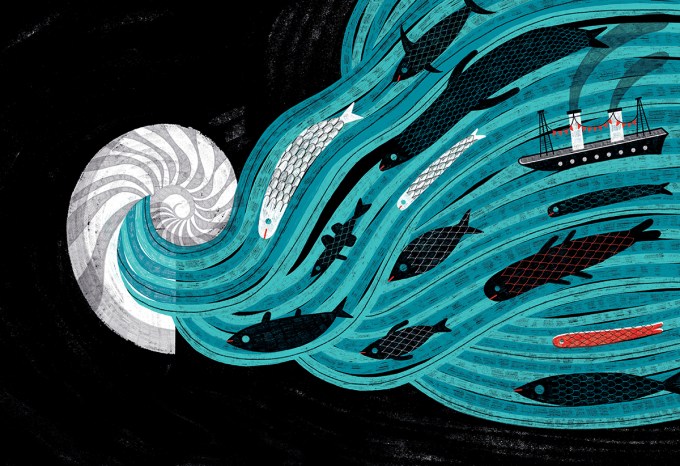

Illustrations courtesy of Enchanted Lion Books; photographs by Maria Popova

Three and a half centuries after Kepler composed his Harmony of the World, envisioning the Earth as an ensouled body that breathes and sounds — a vision that landed his mother in a witchcraft trial — and a century after Ernst Haeckel birthed the notion of ecology, Neruda asks:

His Book of Questions (public library) now comes alive in a stunning bilingual picture-book, illustrated by Chilean artist Paloma Valdivia, whose father grew up in the same coastal region that shaped Neruda’s boyhood and whose grandmother was friends with Neruda’s sister.

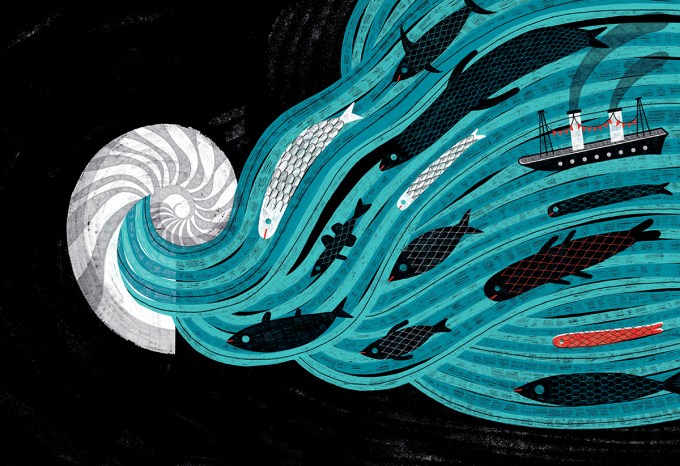

Many are aimed at bodies of water, evocative of poet, painter, and philosopher Etel Adnan’s sublime meditation on the sea and the soul.

Some both sting and salve with their almost unbearable soulfulness:

Complement the paper-cast enchantment that is this Book of Questions with Neruda’s love letter to the forest, his ode to silence, his stirring Nobel Prize acceptance speech, and a lovely picture-book about his life, then revisit artist Margaret C. Cook’s stunning century-old illustrations for Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass.

Pablo Neruda (July 12, 1904–September 23, 1973) channeled 320 such questions — questions earthly and cosmic about art and life, dreams and death, nature and human nature; magical-realist questions that could have been asked by a child or a sage — into his final work of poetry, originally published months before his sudden death.

Do unshed tears

wait in little lakes?

“To lose the appetite for meaning we call thinking and cease to ask unanswerable questions,” Hannah Arendt wrote in her superb meditation on the life of the mind, would mean to “lose not only the ability to produce those thought-things that we call works of art but also the capacity to ask all the answerable questions upon which every civilization is founded.”

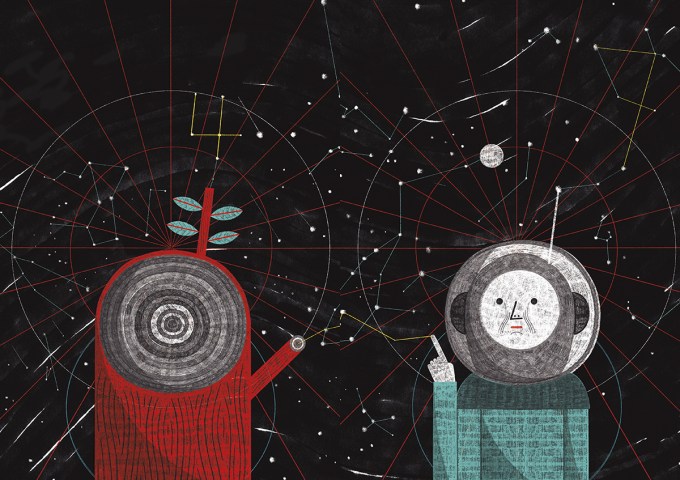

Why do trees hide

the splendor of their roots?

Some break us free from the solitary confinement of our own consciousness:

Valdivia reflects in her artist’s afterword:

But our questions, besides having the power to civilize us, also have the power — perhaps even more needed today — to rewild us.

Illustrating these poems was like deciphering a map of the poet, exploring the territories of his words, looking for meanings in his houses and among his collections, tracing symbolic pathways — only to arrive at understanding, after five years of creative labor, that there are no answers, only more questions arising from Neruda’s questions.

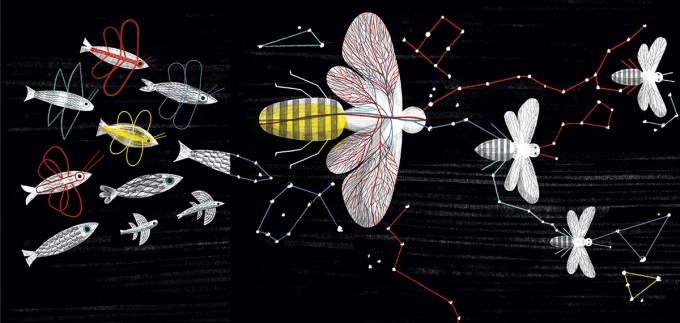

Does the earth chirp like a cricket

in the symphony of the skies?

Why do the waves ask me

the same questions I ask them?

Of Neruda’s original questions — each of them unanswerable, all of them worth asking, crackling with some vital spark of playfulness or poignancy — seventy come ablaze amid the vibrant illustrations and fold-out delights, radiant with the colors and textures of Latin American tapestry.

What emerges is the abstract, lyrical counterpart to the questions of meaning Tolstoy faced at the end of his own days.

Given Valdivia’s roots and her personal resonance with Neruda, many of the illustrated questions are chosen for and filtered through the lens of landscape and its ecosystems.

Some are laced with the abstract wonderment of astronomy.

Is 4, 4 for everyone?

Are all sevens the same?