In his altogether superb essay collection About This Life: Journeys on the Threshold of Memory (public library) — which also gave us his insight into the role of pattern, perspective, and trust in storytelling — he considers the essence of the art, into which he arrived through the portal of anthropology:

Lopez recounts how once, on a long trans-Pacific flight, his seat-mate discerned his occupation, professed that his thirteen-year-old daughter aspired to become a writer, and asked his advice.

If I were asked what I want to accomplish as a writer, I would say it’s to contribute to a literature of hope. With my given metaphors, rooted in a childhood spent outdoors in California and which take much of their language from Jesuit classrooms in New York City, I want to help create a body of stories in which men and women can discover trustworthy patterns.

Complement with George Saunders on the key to great storytelling, Maurice Sendak on music as the secret to storytelling, Anton Chekhov’s six rules for a great story, and Jeanette Winterson’s ten tips on writing (which apply to just about all creative work), then revisit Beethoven’s touching letter of advice to a little girl who had asked him what it takes to be an artist.

One of the most poignant, precise takes on the power and secret of storytelling I have ever encountered comes from Barry Lopez (January 6, 1945–December 25, 2020), whose vast and varied body of work illuminates with uncommon radiance the interleaving of nature and human nature — the way our relationship with Earth and the universe shapes our relationship with ourselves and each other.

At its best, storytelling dilates the locus of you to locate the doom and glory in the knowledge that we are each a part of something greater than ourselves; to make of that knowledge something greater than an identity. Something we might call belonging. Something we might call transcendence.

Looking back on his own aspiration from the fortunate lookout of a long and accomplished life, he reflects:

Read. Find out what you truly believe. Get away from the familiar. Every writer… will offer you thoughts about writing that are different, but these are three I trust.

- Tell her to read… Tell her to read whatever interests her, and protect her if someone declares what she’s reading to be trash. No one can fathom what happens between a human being and written language. She may be paying attention to things in the words beyond anyone else’s comprehension, things that feed her curiosity, her singular heart and mind. Tell her to read classics like The Odyssey. They’ve been around a long time because the patterns in them have proved endlessly useful, and, to borrow Evan Connell’s observation, with a good book you never touch bottom. But warn your daughter that ideas of heroism, of love, of human duty and devotion that women have been writing about for centuries will not be available to her in this form. To find these voices she will have to search. When, on her own, she begins to ask, make her a present of George Eliot, or the travel writing of Alexandra David-Neel, or To the Lighthouse.

- Tell your daughter that she can learn a great deal about writing by reading and by studying books about grammar and the organization of ideas, but that if she wishes to write well she will have to become someone. She will have to discover her beliefs, and then speak to us from within those beliefs. If her prose doesn’t come out of her belief, whatever that proves to be, she will only be passing along information, of which we are in no great need. So help her discover what she means.

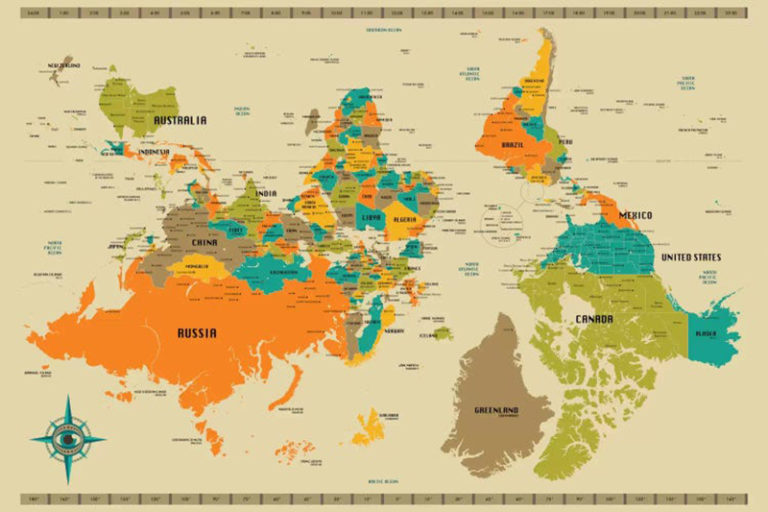

- Tell your daughter to get out of town, and help her do that. I don’t necessarily mean to travel to Kazakhstan, or wherever, but to learn another language, to live with people other than her own, to separate herself from the familiar. Then, when she returns, she will be better able to understand why she loves the familiar, and will give us a fresh sense of how fortunate we are to share these things.

He instructed the man to tell her three things: the first evocative of W.E.B. Du Bois’s advice to his own teenage daughter; the second of Rachel Carson’s assurance that “if you write what you yourself sincerely think and feel and are interested in… you will interest other people”; the third of Susan Sontag’s insistence that the writer’s job is “to make us see the world as it is, full of many different claims and parts and experiences.”

With an eye to his formative childhood passion for raising tumbler pigeons and releasing them into the open sky — “an experience so exhilarating I would turn slowly under them in circles of glee” — he adds:

This is what Lopez offered the eager father beside him:

In all human societies there is a desire to love and be loved, to experience the full fierceness of human emotion, and to make a measure of the sacred part of one’s life. Wherever I’ve traveled — Kenya, Chile, Australia, Japan — I’ve found that the most dependable way to preserve these possibilities is to be reminded of them in stories. Stories do not give instruction, they do not explain how to love a companion or how to find God. They offer, instead, patterns of sound and association, of event and image. Suspended as listeners and readers in these patterns, we might reimagine our lives. It is through story that we embrace the great breadth of memory, that we can distinguish what is true, and that we may glimpse, at least occasionally, how to live without despair in the midst of the horror that dogs and unhinges us.

Without story, there is no self. For all human beings, internal narrative is the pillar of memory and identity. For the subset of our species who identify as writers, storytelling is the shape we give to our longing to comprehend and connect with the world. “Storytelling is a tool for knowing who we are and what we want,” wrote Ursula K. Le Guin, that exquisite specimen of the subset. The storyteller’s role, wrote the exquisite Baldwin, is “to make you realize the doom and glory of knowing who you are and what you are.”

Looking at the father trying to absorb it all, Lopez distilled his advice:

Every story is an act of trust between a writer and a reader; each story, in the end, is social. Whatever a writer sets down can harm or help the community of which he or she is a part. When I write, I can imagine a child in California wishing to give away what he’s just seen — a wild animal fleeing through creosote cover in the desert, casting a bright — eyed backward glance. Or three lines of overheard conversation that seem to contain everything we need understand to repair the gaping rift between body and soul. I look back at that boy turning in glee beneath his pigeons, and know it can take a lifetime to convey what you mean, to find the opening. You watch, you set it down. Then you try again.