In her classic on the sublime and the good — which includes the finest definition of love, and was later included in the posthumous Murdoch anthology Existentialists and Mystics: Writings on Philosophy and Literature (public library) — freedom emerges as a primary lens on the beautiful, the sublime, and the good.

Looking back on the history of literature since antiquity, she derives a kind of pocket history of freedom — of our ideas about it — in five roughly chronological phases:

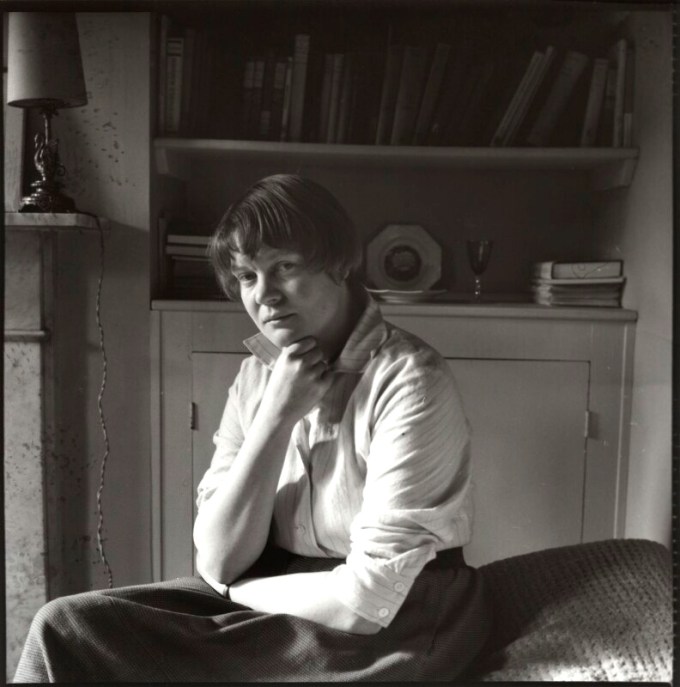

“Nothing is more unbearable, once one has it, than freedom,” James Baldwin wrote in one of the greatest novels of the twentieth century. At the same time, across the Atlantic, Iris Murdoch (July 15, 1919–February 8, 1999) was aiming her uncommonly penetrating intellect at the history of art — and literary art in particular, with its pinnacle in the novel — as an instrument of freedom.

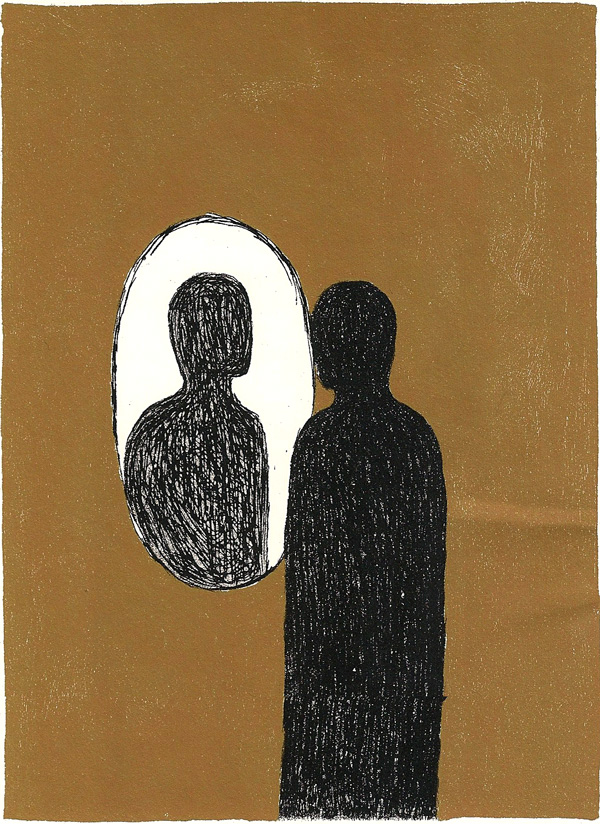

In literature — in this the common record of human thought and feeling, in this sandbox in which we play out our reckonings with the most urgent and eternal questions of existence — we can find a history of freedom, of our ideas about what it means to be free, inseparable from our ideas about love, inseparable from what Murdoch calls “the tragic freedom implied by love” — tragic because it is rooted in the fundamental and fundamentally discomposing fact that “others are, to an extent we never cease discovering, different from ourselves.”

Murdoch examines the relationship between freedom and love in confronting and reconciling difference:

Freedom is our ability to rise out of history and grasp a universal idea of order which we then apply to the sensible world.

Although Murdoch never lived to see this pandemic of selfing, in art and life, she furnished us with the antidote to it: the willingness to rise beyond ourselves — beyond our selves, which include our personal position in spacetime and our personal experience of the events unfolding in it — so that we may see a fuller picture of reality:

- TRAGIC FREEDOM: This is the concept of freedom which I have related to the concept of love: freedom as an exercise of the imagination in an unreconciled conflict of dissimilar beings. It belongs especially to, was perhaps invented by, the Greeks. The literary form is tragic drama.

- MEDIEVAL FREEDOM: Here the individual is seen as a creature within a partly described hierarchy of theological reality. The literary forms are religious tales, allegories, morality plays.

- KANTIAN FREEDOM: This belongs to the Enlightenment. The individual is seen as a non-historical rational being moving towards complete agreement with other rational beings. The literary forms are rationalistic tales and allegories and novels of ideas.

- HEGELIAN FREEDOM: This belongs mainly to the nineteenth century. The individual is now thought of as a part of a total historical society and takes his importance from his role in that society. The literary form is the true novel (Balzac, George Eliot, Dickens).

- ROMANTIC FREEDOM: This belongs mainly to the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, though it has its roots earlier. The individual is seen as solitary and as having importance in and by himself. Both Hegelian and Romantic freedom are of course developments of Kantian freedom. Hegel makes the Kingdom of Ends into a historical society; while the Romantic concludes from the unhistorical emptiness of Kant’s other rational beings that in fact one may as well assume that one is alone. (This is one line of thought leading to existentialism. Angst is the modern version of Achtung [Kant’s notion of the experience of respect for moral law]; we now fear, not the law itself, but its absence.) The literary form is the neurotic modern novel… The novel fails to be tragic because, in almost every case, it succumbs to one of the two great enemies of Love, convention and neurosis. The nineteenth-century novel succumbed to convention, the modern novel succumbs to neurosis. The nineteenth-century novel is better than the twentieth-century novel because convention is the less deadly of the two.

Freedom is exercised in the confrontation by each other, in the context of an infinitely extensible work of imaginative understanding, of two irreducibly dissimilar individuals. Love is the imaginative recognition of, that is respect for, this otherness.

To this I would add that in the twenty-first century, we have invented a third and greatest enemy of Love: selfing. We are rapidly approaching the event horizon of a literary landscape in which there are more memoirs than there are novels, a landscape in which the light of the empathic and speculative imagination has been eclipsed by the recursive self-reference of the human ego. We are seeing this play out in varying degrees in all the arts, from photography to poetry, and we are participating in it, as creators or celebrators, forgetting somehow that the way to be interesting is to be interested — in something other than oneself; that to be an artist is to be wide-eyed with wonder at the world beyond one’s own skin and experience, and to transmute this wonder into quickenings of beauty and meaning, which grant us, in Murdoch’s lovely term, “an occasion for unselfing.”

This is the truest test of art and the ultimate frontier of freedom.

Complement this fragment of Existentialists and Mystics — which also gave us Murdoch on truth and the meaning of goodness, art as a force of resistance, and the key to great storytelling — with Erich Fromm on the paradox of freedom and Alan Watts on its most elusive meaning, then revisit the philosopher of mind Amélie Rorty on the seven layers of identity in literature and life.

The memoir is the selfie of literature. Even at its best, it is the sub-art of skillful selfing; at its worst, it hovers between self-help and self-vindication. In our phase of history, in our literature and our art, we have forgotten something fundamental: We are nowhere less free than in the trap of the self. We are also nowhere less capable of Love — for love, as Murdoch herself put it in her superb definition, is “the extremely difficult realisation that something other than oneself is real.”