Sound, color, and wonderment where the body meets the soul.

By Maria Popova

[embedded content]

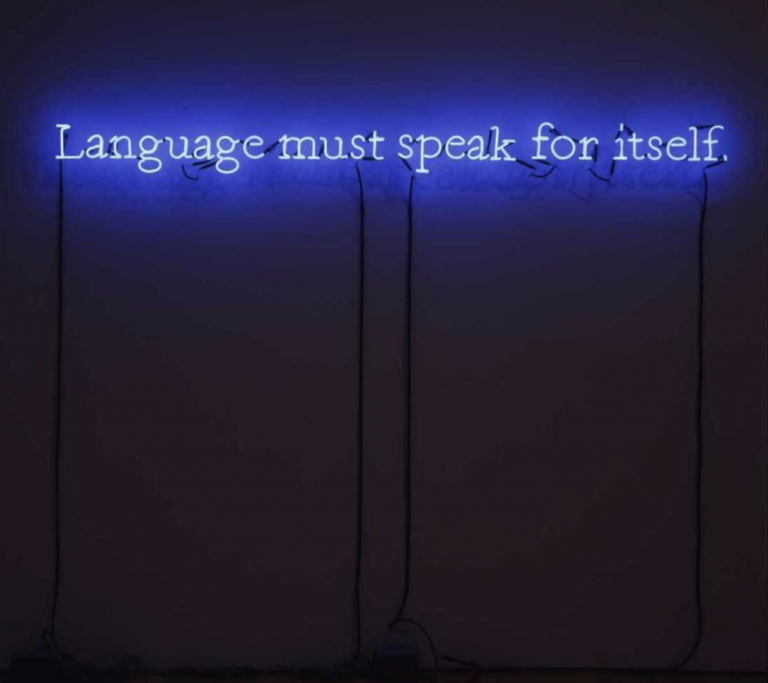

Inspired by communal ritual dances and drawing on conversations with a musician, a music therapist, a neuroscientist, and several dancers, the film is part visual sketchbook of recorded sounds and part abstract existential inquiry. What emerges is a subtle meditation on the limitations of words — that is, of disembodied language — in conveying emotional meaning, which is (as Whitman well knew) an ongoing dialogue between the body and the soul, cerebral and sensorial at the same time, a quickening of thought and feeling that moves through us as we move through the world.

Half a century earlier, Virginia Woolf exulted in how music and dance rehumanize us, how “dance music… stirs some barbaric instinct — lulled asleep in our sober lives — [so that] you forget centuries of civilization in a second.”

Generations after Whitman, after Woolf, after Watts, artist Lottie Kingslake — who animated the stunning poem-song “Singularity” for The Universe in Verse — shines a sidewise gleam on these questions in her lovely animated film So I Danced Again…

It’s very hard, finding words for things, isn’t it? Finding the words for things. But, then, perhaps we shouldn’t be thinking about it too much, and just enjoying it.

“If the universe is meaningless, so is the statement that it is so,” Alan Watts quipped as he aimed his wry wisdom at the paradox of our search for meaning. “The meaning and purpose of dancing is the dance.”