Punctuating the incantations of what women may not do is the sudden, striking, almost ironic chorus line:

These might seem like amusing specimens from the fossil record of culture, but they encode the broader and darker history of regulating women’s sovereignty of sinew and spirit — our autonomy of over our own bodies: how we move them through the world and how the world moves through them. Today, with neuroscience finally affirming what the poets and philosophers have long known — that consciousness is a full-body phenomenon, or as Walt Whitman memorably put it in Maria Ward’s time, that the body is the soul — it is more plainly evident than ever that regulatory control of the body is a bid for control of the mind, of the soul, of consciousness itself.

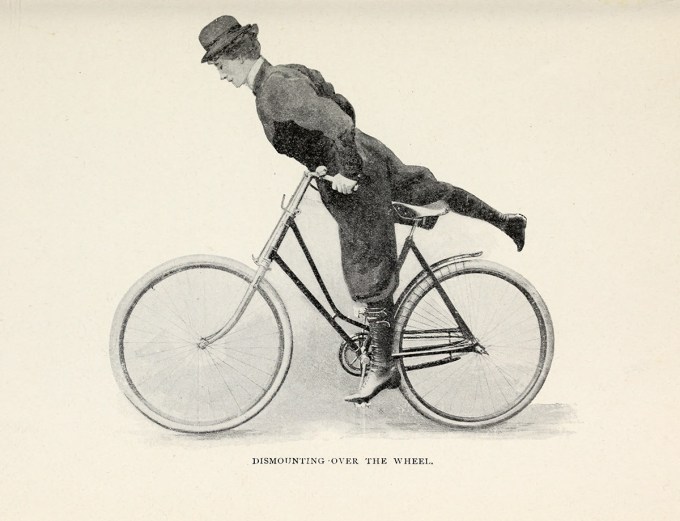

“You are at all times independent. This absolute freedom of the cyclist can be known only to the initiated,” Maria Ward wrote in her blazing 1896 manifesto Bicycling for Ladies, celebrating the bicycle as an instrument of emancipation, self-reliance, and unselfconscious joy a year after the New York World published its tragicomical list of don’ts for women on two wheels.

That is what visionary composer and National Sawdust founder Paola Prestini explores with elegance and enchantment in her piece Biking Through Time, which I had the pleasure of seeing performed live by the Brooklyn Youth Chorus — the constellation of young people who, several springs earlier, brought to life David Byrne’s countercultural anthem of resistance and resilience.

You may ride a bike!

No… no… must comply with your husband.

You may ride a bike!

No… no… must comply with your husband.

You may ride a bike!

No… no… no… no… no… no… no… no…

Complement with “Thrush Song” — the haunting choral tribute to Rachel Carson, on which Paola and I collaborated for the 2020 Universe in Verse, brought to life by another constellation of young voices — then revisit the trailblazing life and art of Alice Austen, who mounted fifty pounds of photography equipment on her bicycle to become a pioneer of street photography and the nineteenth century’s foremost documentarian of queer culture.

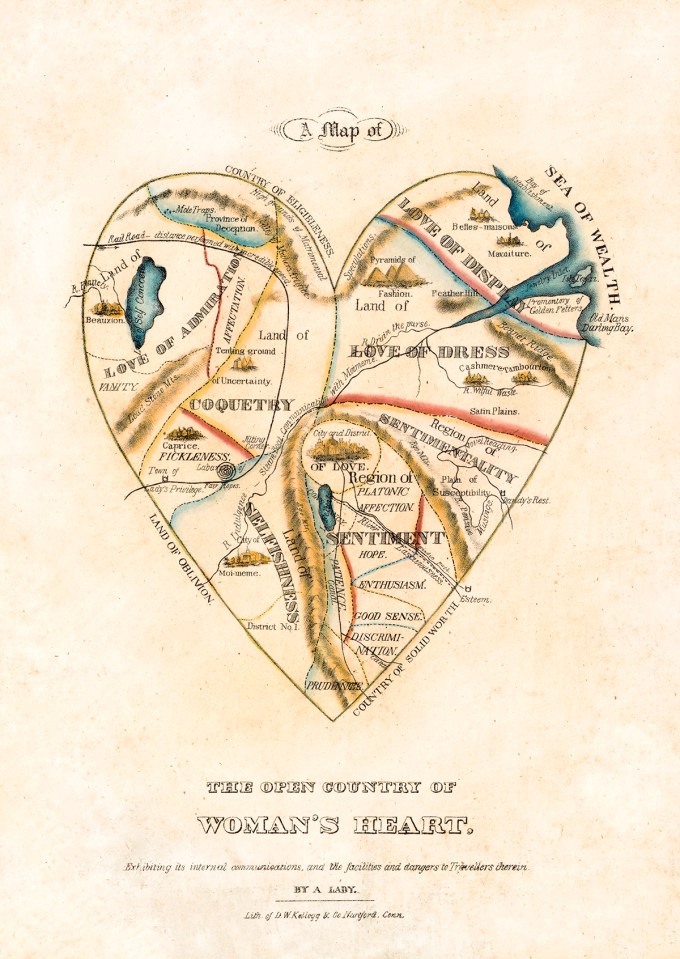

Anchored in three historical artifacts — this “map of woman’s heart” from the first half of the nineteenth century, satirizing Victorian gender stereotypes; the aforementioned list of don’ts for women on bicycles from the end of the nineteenth century, which includes dicta like “don’t faint on the road,” “don’t scream if you meet a cow,” and “don’t try to ride in your brother’s clothes to see how it feels”; and these rules of conduct for women, pinned on the door of a Spanish church in the 1960s, which decree that “no decent woman or girl is ever seen on a bicycle” — the piece then time-travels to “the land of the free,” synthesizing some of the legally sanctioned don’ts for American women in the 1970s: no credit cards, no Ivy League education, no protection from sexual harassment in the workplace, no legal access to birth control.

[embedded content]

Suddenly, the piece becomes a sort of cultural elegy, in the classic sense of celebration and lamentation fused into one, reminding us just how long the arc of progress is, how much of what we take for granted today is the hard-won victory of generations past (as I realized afresh, having ridden my bicycle to the nineteenth-century fishery turned event space where the young people sang), and how, as Zadie Smith observed in her electrifying meditation on optimism and despair, “progress is never permanent, will always be threatened, must be redoubled, restated and reimagined if it is to survive.”