Science was one of Maria Mitchell’s two great passions. The other was poetry.

THE ANIMATED UNIVERSE IN VERSE: CHAPTER THREE

ACHIEVING PERSPECTIVE

by Pattiann Rogers

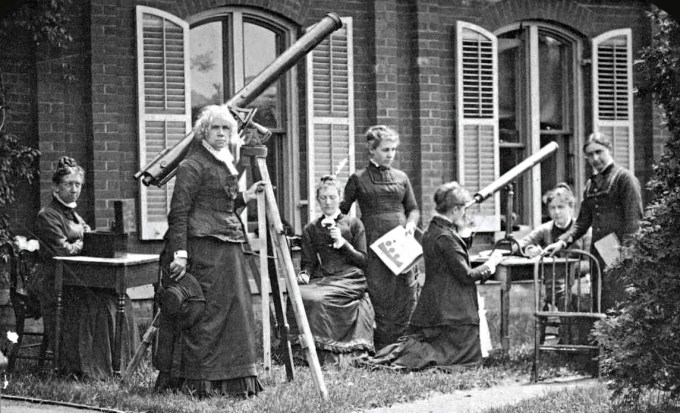

America’s first professional female astronomer, she was also the first woman employed by the federal government for a “specialized non-domestic skill.” After discovering her famous comet, she was hired as “computer of Venus,” performing complex mathematical calculations to help sailors navigate the globe — a one-woman global positioning system a century and a half before Einstein’s theory of relativity made GPS possible.

It was this living example that became Maria Mitchell’s great poem, composed in language of being — as any life of passion and purpose ultimately becomes.

Two centuries ago, Maria Mitchell — a key figure in Figuring — understood this with uncommon poetry of perspective.

And even in the gold and purple pretense

Of evening, I make myself remember

That it would take 40,000 years full of gathering

Into leaf and dropping, full of pulp splitting

And the hard wrinkling of seed, of the rising up

Of wood fibers and the disintegration of forests,

Of this lake disappearing completely in the bodies

Of toad slush and duckweed rock,

40,000 years and the fastest thing we own,

To reach the one star nearest to us.

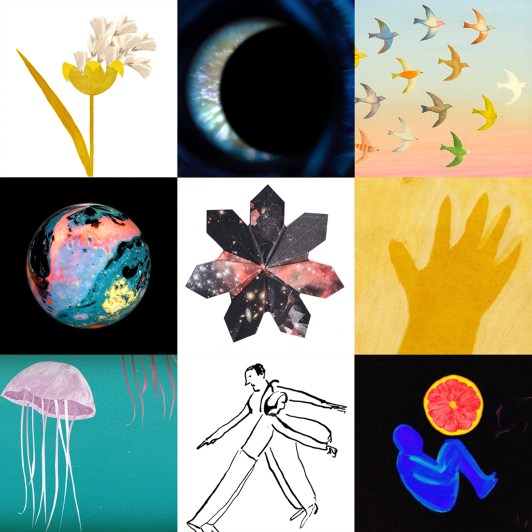

Published in her collection Firekeeper (public library), it is read for us here by the ever-optimistic David Byrne, with original art by his ever-perspectival longtime collaborator Maira Kalman and original music by the symphonic-spirited Jherek Bischoff.

Maria Mitchell’s students went on to become the world’s first class with academic training in what we now call astrophysics. They happened to all be women.

And when you speak to me like this,

I try to remember that the wood and cement walls

Of this room are being swept away now,

Molecule by molecule, in a slow and steady wind,

And nothing at all separates our bodies

From the vast emptiness expanding, and I know

We are sitting in our chairs

Discoursing in the middle of the blackness of space.

And when you look at me

I try to recall that at this moment

Somewhere millions of miles beyond the dimness

Of the sun, the comet Biela, speeding

In its rocks and ices, is just beginning to enter

The widest arc of its elliptical turn.

[embedded content]

When Maria Mitchell began teaching at Vassar College as the only woman on the faculty, the college handbook mandated that neither she nor her female students were allowed outside after nightfall — a somewhat problematic dictum, given she was hired to teach astronomy. She overturned the handbook and overwrote the curriculum, creating the country’s most ambitious science syllabus, soon copied by other universities — including the all-male Harvard, which had long dropped its higher mathematics requirement past the freshman year.

“Mingle the starlight with your lives,” she often told her students, “and you won’t be fretted by trifles.”

Mitchell taught astronomy until the very end of her long life, when she confided in one of her students that she would rather have written a great poem than discovered a great comet. But scientific discovery is what gave her the visibility to blaze the way for women in science and enchant generations of lay people the poetry of the cosmic perspective.

At her regular “dome parties” inside the Vassar College Observatory, which was also her home, students and occasional esteemed guests — Julia Ward Howe among them — gathered to play a game of writing extemporaneous verses about astronomy on scraps of used paper: sonnets to the stars, composed on the back of class notes and calculations.

Previously on The Universe in Verse: Chapter 1 (the evolution of flowers and the birth of ecology, with Emily Dickinson); Chapter 2 (Henrietta Leavitt, Edwin Hubble, and the age of space telescopes, with Tracy K. Smith).

And yet here we are, our transient lives constantly fretted by trifles as we live them out in the sliver of spacetime allotted us by chance.

This is the third of nine installments in the 2021/2022 animated season of The Universe in Verse in collaboration with On Being, celebrating the wonder of reality through stories of science winged with poetry. Here are Chapter 1 (the evolution of flowers and the birth of ecology, with Emily Dickinson) and Chapter 2 (Henrietta Leavitt, Edwin Hubble, and the human hunger to know the cosmos, with Tracy K. Smith).

Straight up away from this road,

Away from the fitted particles of frost

Coating the hull of each chick pea,

And the stiff archer bug making its way

In the morning dark, toe hair by toe hair,

Up the stem of the trillium,

Straight up through the sky above this road right now,

The galaxies of the Cygnus A cluster

Are colliding with each other in a massive swarm

Of interpenetrating and exploding catastrophes.

I try to remember that.