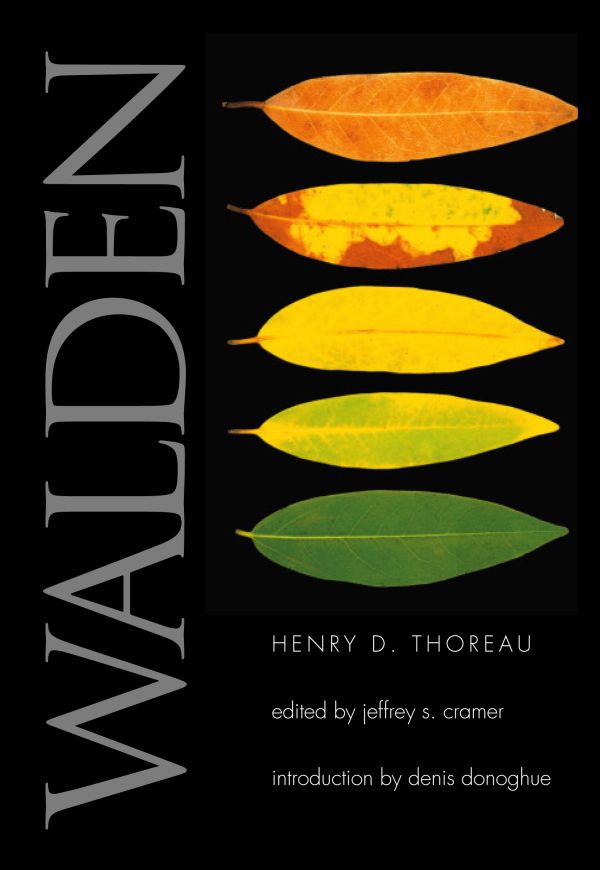

In the spring of 1936 — while waiting for his beloved to arrive from London for their wedding, contemplating enlisting in the Spanish Civil War, and germinating the ideas that would bloom into Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four — Orwell planted some roses in the garden of the small sixteenth-century cottage that his suffragist, socialist, bohemian aunt had secured for him in the village of Wallington.

PROBABLE IMPOSSIBILITIES

With a foreword by the poetic bryologist Robin Wall Kimmerer, and contributions as variegated as Ursula K. Le Guin’s love-poem to trees and arborist William Bryant Logan’s revelatory meditation on immortality and the music of trees, the anthology is a cathedral of wonder and illumination.

I don’t think art has a duty to be beautiful or uplifting, and some of the work I’m most drawn to refuses to traffic in either of those qualities. What I care about more… are the ways in which it’s concerned with resistance and repair.

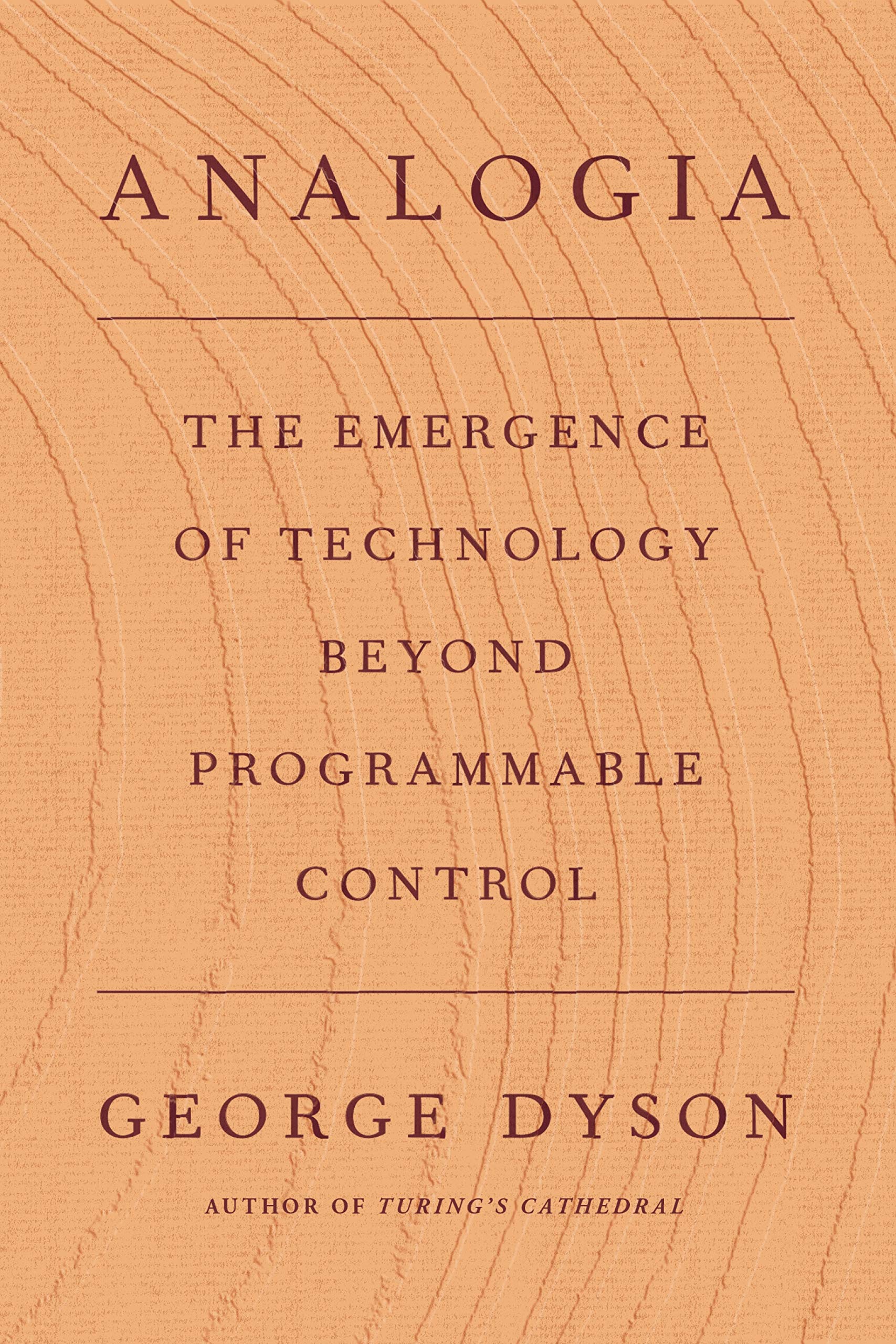

In the fourth epoch, so gradually that almost no one noticed, machines began taking the side of nature, and nature began taking the side of machines. Humans were still in the loop but no longer in control. Faced with a growing sense of this loss of agency, people began to blame “the algorithm,” or those who controlled “the algorithm,” failing to realize there no longer was any identifiable algorithm at the helm. The day of the algorithm was over. The future belonged to something else.

ORWELL’S ROSES

In the fourth epoch, so gradually that almost no one noticed, machines began taking the side of nature, and nature began taking the side of machines. Humans were still in the loop but no longer in control. Faced with a growing sense of this loss of agency, people began to blame “the algorithm,” or those who controlled “the algorithm,” failing to realize there no longer was any identifiable algorithm at the helm. The day of the algorithm was over. The future belonged to something else.

ANALOGIA

In the fourth epoch, so gradually that almost no one noticed, machines began taking the side of nature, and nature began taking the side of machines. Humans were still in the loop but no longer in control. Faced with a growing sense of this loss of agency, people began to blame “the algorithm,” or those who controlled “the algorithm,” failing to realize there no longer was any identifiable algorithm at the helm. The day of the algorithm was over. The future belonged to something else.

FUNNY WEATHER

In the fourth epoch, so gradually that almost no one noticed, machines began taking the side of nature, and nature began taking the side of machines. Humans were still in the loop but no longer in control. Faced with a growing sense of this loss of agency, people began to blame “the algorithm,” or those who controlled “the algorithm,” failing to realize there no longer was any identifiable algorithm at the helm. The day of the algorithm was over. The future belonged to something else.

A SWIM IN A POND IN THE RAIN

In the fourth epoch, so gradually that almost no one noticed, machines began taking the side of nature, and nature began taking the side of machines. Humans were still in the loop but no longer in control. Faced with a growing sense of this loss of agency, people began to blame “the algorithm,” or those who controlled “the algorithm,” failing to realize there no longer was any identifiable algorithm at the helm. The day of the algorithm was over. The future belonged to something else.

OLD GROWTH

Few people have understood this more clearly or offered more potent calibration for it than Marcus Aurelius (April 26, 121–March 17, 180).

Peek inside here.

Read more and peek inside here.

Our ancient bond with trees as companions and mirrors of our human experience comes alive afresh in Old Growth — a wondrous anthology of essays and poems about trees, culled from the decades-deep archive of Orion Magazine.