In some of his recent courses, Daniel Munro, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Toronto, has tried assigning something different from the traditional essays and exams: creative public philosophy projects.

Engaging Students’ Diverse Background Skills. A diverse student body means that different students are comfortable working in different media and genres. Some are naturally disposed to writing academic essays, while others may never become fully comfortable with them. We can make philosophy more accessible and relatable to a diverse set of students by offering opportunities to do philosophy in less traditional ways. A computer science major might feel especially at home coding an interactive computer game, as did my student Alice Zhang. A singer-songwriter might be comfortable expressing himself through song, as was my student RJ Paz-Viray.

Assigning Public Philosophy Projects to Undergraduates

by Daniel Munro

I’d love to hear from other instructors who have used assignments like this: what have you done that’s worked particularly well, and what do you see as the benefits and limitations? Or, if you’ve only thought about using this sort of assignment but haven’t done so, what’s stopping you?

Screenshot from Muhammad Abdurrahman’s video review of Her

- Create a YouTube video or podcast.

- Propose a substantive edit to a Wikipedia article or propose an entirely new Wikipedia article.

- Write a philosophical op-ed or blog post.

- Conduct a philosophically substantive interview with someone whose work is related to course content (philosopher, academic, artist, journalist, etc.).

- Utilize another online medium or social media platform (Reddit, Twitter, Facebook, etc.), perhaps by designing some way to engage non-course participants in philosophical activity.

I’ve had students produce everything from YouTube videos and blog posts to recorded songs and computer games (read on to see some examples from my recent “Minds and Machines” course). After several iterations, I’ve had the chance to reflect on the benefits and limitations of this sort of assignment.

Pedagogical Benefits

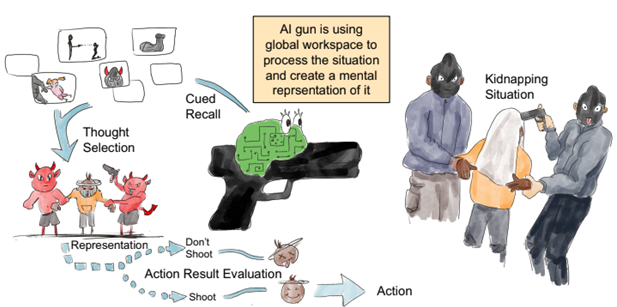

Screenshot from Kristal Menguc’s illustrated essay on AI-powered guns

In several recent undergraduate courses, I’ve offered students the option to design a creative “public philosophy project” in lieu of writing a traditional term paper. Typically, around 10-15% of students choose this option, and I’m consistently impressed with the quality and creativity of their work.

In the following guest post,* he talks about both the benefits and drawbacks of assignments like this, and solicits suggestions and ideas from others who have (or have thought of) giving similar assignments.

Student time. Projects like this require more time and effort than writing a paper, since students must design their own topic, design the creative aspects of the project, and work on tasks such as video editing or audio recording. It’s important to be upfront with students about this so that they can start managing their time and expectations early on in the process. I also try to be quite flexible with deadlines to accommodate unforeseen complications or technical difficulties.

Demonstrating the power of philosophy. Through assignments like this, students can use philosophical tools to analyze topics about which they’re personally passionate. They thereby learn how philosophy can help them acquire a deeper understanding of domains outside of their particular course context. In this vein, my student Chang (Hazel) Gao told me she undertook her philosophical interview with a visual artist because she “wanted to understand his artworks better through philosophy.” Similarly, my student Muhammad Abdurrahman produced a philosophical video review of the film Her, while my student Kristal Menguc produced an illustrated essay grappling with the ethics of AI in law enforcement. My hope is that practicing using philosophical tools in these ways will encourage students to continue doing so once they’ve moved on from my courses.

Instructor time. Working closely with students on their projects takes extra time. Because of this, I’m not sure how well this would scale up to an assignment that’s required of all students rather than being optional. In a large class, I expect that sacrificing the opportunity for closer mentorship of each student may make it more difficult for students to plan out their projects.

Limitations and Drawbacks

I let students know about this option at the very beginning of the semester, and I direct them to a blurb on my syllabus with some examples of what their projects might look like, including:

Screenshot from Alice Zhang’s computer game “DUM Academy”

Encouraging a deeper grasp of course material. You must have a good grasp of complex philosophical ideas before you can effectively explain them to non-specialists. Encouraging students to make their work accessible to a general audience thus encourages them to develop a deeper grasp of course material. As my student Alice put it when describing how she developed her computer game: “an important part of the project was that it had to be public, meaning that others outside of the course should be able to access it. While developing my game, many of my friends wanted to play through and test it. Helping them understand my game and trying to explain course content to them made for a much more enriching learning experience.”

- Students often implicitly assume that their audience has some shared background knowledge of course material. Accordingly, their writing typically leaves some gaps in explanation, and as non-experts they’re not always able to recognize and fill these gaps. This is often replicated in their projects, despite their conscious attempt to create public-facing work. For many students, producing work that’s genuinely suitable for public consumption would require more rounds of editing and revision than are possible within a single semester.

- As with most student work, there are typically some inaccuracies in students’ explanations of other philosophers’ ideas. These would also need to be ironed out through more editing and revision before their work could be truly public-facing.

Public-facing work by non-experts. There are a couple of limitations involved in tasking non-experts with producing public-facing work:

Given the open-ended nature of this assignment, I work more closely with each student than I would on a traditional paper. I require them to send in their initial ideas several weeks before the end of the term, and I typically meet with each student once or twice (or exchange several emails) to hash out their plans. Students often initially propose projects that involve merely explaining other philosophers’ ideas for a general audience. So, we often spend some time discussing how to incorporate substantive philosophical work of their own into the specific medium in which they’re working, by making an original argument or doing some kind of comparative work.