Once you’ve identified which journals will consider more philosophical submissions, the main challenge is to demonstrate the import of your ideas for the field in question and to make these ideas accessible to people with no background in philosophy. For this, it’s usually best to point to theoretical debates internal to the field and to highlight how theoretical shortcomings have practical implications. When writing on empathy in nursing, for instance, my co-author and I motivated our work by pointing to recent debates in nursing education, where many researchers expressed concern that, without an agreed-upon definition of empathy, it’s difficult if not impossible for them to assess the effectiveness of empathy training programs.

When it comes to establishing an inter- or transdisciplinary career, there’s plenty more to discuss: applying for grants in other fields, seeking out academic jobs outside of philosophy, teaching philosophy to people who are already experts in other fields, learning and refining new research methods, and managing your disciplinary identity, to name just a few. But I hope that a focus on familiarity, networking, and publishing provides a helpful starting point for those who are thinking of stepping outside of philosophy (but not outside of academia).

By attending these conferences and events, I also got a sense of the general dissatisfaction felt by both clinical and academic psychiatrists. In my experience, people turn to philosophy when they’re frustrated or unsatisfied with the theoretical foundations of their field. So, these kinds of interdisciplinary events tend to attract people who are more than happy to tell you about all the issues they see in their field and to share their ideas about how philosophy might help them intervene. Events like these can also be a great opportunity to find mentors and start interdisciplinary collaborations. Eventually, you’ll probably want the audience for your work to expand beyond those researchers who have already decided that philosophy is useful for their discipline. But it’s the researchers who are already interested in philosophy who will help you reach that audience.

Stepping Outside of Philosophy:

Reflections on a Transdisciplinary Career

by Anthony Vincent Fernandez

To start, I think it’s best to find researchers who are already interested in philosophy and who have cultivated philosophical sensibilities. But where are you supposed find them? In my experience, the best opportunities for constructive, face-to-face interaction with researchers in other fields have been at interdisciplinary philosophy conferences. I relied a lot on the networks I built at meetings of the International Network for Philosophy and Psychiatry (INPP) and the Association for the Advancement of Philosophy and Psychiatry (AAPP). Many of the participants were psychiatrists and clinical psychologists. Some had formal training in philosophy, whereas others were self-taught. In either case, their philosophical background provided a shared intellectual space for productive dialogue and debate

If, however, you do want to write a longer, more philosophical piece for a major scientific journal, there may still be opportunities to do this. In my case, I wanted to write longer pieces on how phenomenological concepts, such as empathy and embodiment, can be used in nursing research and practice. I could have aimed to publish these articles in philosophy of medicine journals. But I wanted to write directly to people working in health care. After sifting through the article types in the submission guidelines and talking with nursing researchers about where they publish more philosophically oriented ideas, I found two or three journals among the top 10 that were at least open to this kind of work. The International Journal of Nursing Studies, for instance, is flexible on article structure and allows submissions that are written more like a typical philosophy article, albeit with the caveat that it should be accessible to nurses without a philosophical background. The Journal of Clinical Nursing, on the other hand, is fairly rigid in its structure—articles need to include the typical sections (i.e., Aims and Objectives, Background, Design, Method, and so on). However, I found that some authors had managed to get more theoretical work published in this journal by writing a single line as the entire Design section, which started with “This is a discursive article….” That was enough to signal to the editors and reviewers that the content of the article differs in substantial respects from their typical articles, while still (technically) conforming to their standard article structure.

Networking. Once you’ve established enough familiarity to feel comfortable with another field, how do you find researchers to engage or collaborate with? Even if the topics and issues you’re interested in are ones that resonate with a large portion of researchers in the respective field, explaining how your philosophical work might have a positive impact on this field can be a challenging task. Many researchers, even those who are more theoretically inclined, may find it unusual to think about issues in a philosophical way.

Today, universities and grant agencies relentlessly push us to develop “interdisciplinarity” and even “transdisciplinarity” research programs. But the structure of academic training remains monodisciplinary: we receive years of formal training on discipline-specific knowledge and research methods, as well as informal training on the discipline-specific norms governing, for instance, presentations, publications, networking, and collaboration. When it comes to inter- or transdisciplinary training, on the other hand, we’re expected to figure it out ourselves. I think, however, that there’s plenty of generalizable guidance that we might share. In this post, I take the opportunity to reflect on some of the challenges I’ve encountered in my own career to provide some guidance for early career researchers based in philosophy who want to engage or collaborate with researchers in other disciplines.

First, a few lines about me. I’ve aimed for an interdisciplinary career from the start, engaging and collaborating with researchers in a variety of fields, including psychiatrists, clinical psychologists, and nurses. Recently, I moved from a position in a philosophy department to a new position in a department of sports science and clinical biomechanics, where I now work alongside sports scientists and rehabilitation therapists. My primary philosophical background is in phenomenology and continental philosophy. And most of my work is on issues related to health and illness. However, my reflections here are on issues that I hope are generalizable to anyone working in philosophy who wants to engage with researchers in other fields. I’ve decided to limit my reflections to three key themes—Establishing Familiarity, Networking, and Publishing—which I hope will provide a good starting point for graduate students and early career researchers. But there are plenty more challenges to discuss.

Starting with a standard scientific article might seem daunting. Articles in most scientific fields look much different from philosophy articles. However, scientific journals often have multiple article types. If you’re trying to familiarize yourself with philosophical debates in another field, then it can be helpful to skim over editorials, commentaries, and letters to the editor. These often provide reflections on key issues in the field, including current crises or challenges, recent theoretical or methodological developments, and proposals for new directions in scientific research. It can also be helpful to read blog posts by people who hold high-level administrative roles, such as leaders of major organizations, editors of the top journals, and heads of grant agencies, they not only have a birds-eye-view of the field as a whole—they also play an important role in steering the field itself.

Establishing Familiarity. Once you know which field you want to engage with, the first challenge is to establish some familiarity with it. As a philosopher, the obvious approach to establishing familiarity with another field is to look at work in the “philosophy of X” (philosophy of biology, philosophy of psychology, philosophy of literature, and so on). You’ll probably feel most comfortable with this literature—it’ll be written in a familiar style and engage with authors you’ve already read. But is it the best place to establish familiarity with another academic field? There’s an important difference between philosophical debates about other academic fields and philosophical debates within other academic fields. In some cases, philosophical debates about other academic fields diverge from the interests of researchers in the field in question and, as a result, have little to no impact on that field. So, what’s the alternative? How do you familiarize yourself with philosophical debates playing out in other academic fields?

In this guest post*, Anthony Vincent Fernandez (Assistant Professor of Applied Philosophy at the Danish Institute for Advanced Study & Department of Sports Science and Clinical Biomechanics, University of Southern Denmark, and part-time Research Fellow, Faculty of Philosophy, University of Oxford) provides some guidance for those interested in an interdisciplinary or transdisciplinary academic career, based on his experiences and challenges pursuing one.

Once you’ve become skilled at writing for audiences in other fields and publishing outside of philosophy, does this mean that you’ll have no reason to return to publishing in philosophy journals? For most of us, I don’t think this will ever be the case. There will always be good reasons (even beyond the practicalities of hiring, tenure, and promotion) to publish some of your work in philosophy journals. In my own case, I find it constructive to think through new philosophical ideas without having to clarify, from the start, how exactly these ideas might be applied to another field. Interdisciplinary philosophy journals provide an excellent space to work these ideas out and defend them according to philosophical standards of argumentation. Once you’re satisfied that the ideas are, in fact, philosophically defensible, then you have a theoretical foundation from which you can develop more concrete applications or even engage in collaborative empirical research. In my own case, researchers in other fields have reached out to initiate new collaborations because of my work in interdisciplinary philosophy journals. And I don’t think the ideas I developed in that work could have been published in scientific journals.

* * * * *

In my case, for example, I was interested in theoretical issues in the classification and diagnosis psychiatric disorders. For a big picture view of psychiatry’s general attitude toward the current norms, I read editorials and blog posts by major figures in the field, such as leaders of the US National Institute of Mental Health. Through this literature, I was able to get a sense of where research on psychiatric classification is heading, not just where it’s been (which was the focus of most of the philosophical literature on the topic).

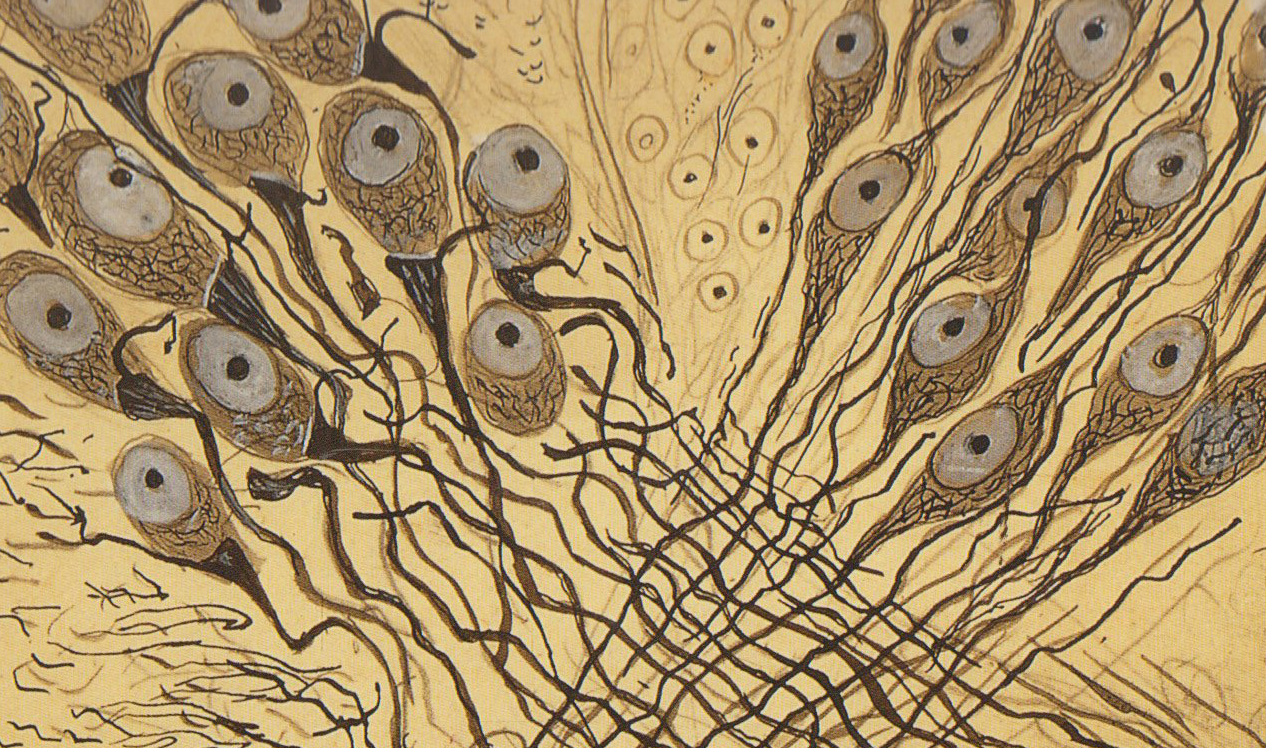

[Santiago Ramón y Cajal, brain illustration (detail)]

With a few exceptions, philosophy journals tend to have only one submission type: a full-length article, usually around 7,000 to 12,000 words. Science journals, on the other hand, usually have numerous submission types. The Lancet journals, for instance, publish around a dozen different types of articles, including editorials, comments, perspectives, hypotheses, and policy pieces, in addition to their standard full-length original research articles. For many science journals, the Original Research category is almost exclusively reserved for reporting the results of empirical studies. If you collaborate with an interdisciplinary team of researchers, then it’s possible to publish in this category. When working on your own or with other philosophers, however, it’s probably more realistic to aim for some of the shorter article types. Editorials, comments, and perspectives, for example, tend not to have a rigid structure. They allow for freeform writing, which most of us in philosophy are more comfortable with.

Publishing. Once you’ve familiarized yourself with a field and developed a research network, how do you go about publishing in this new area? Beyond familiarizing yourself with the current debates and issues, you’ll also need to learn to navigate the publishing norms of a new field. This may include differences in writing style, article structure, reviewing standards, and even new norms governing how to interact with editors and critique other researchers.

Universities say they want their faculty to pursue “interdisciplinary” and “transdisciplinary” work. Yet it might be difficult to figure out how to do that given the structure of academia and the nature of academic training.