THE BOY WHOSE HEAD WAS FILLED WITH STARS

Before I Grew Up (public library) was born — part elegy and part exultation, reverencing the vibrancy of life: the life of feeling and of the imagination, the life of landscape and of light, the life of nature and of the impulse for beauty that irradiates what is truest and most beautiful about human nature.

Here are a handful I wrote about this year and loved with all my heart — a list of loves partial in both senses of the word and invariably incomplete, given the limitations of any one person’s finitude of time and singularity of thought.

Peek inside here.

As she teaches the baby to look at this color, this shape, this quality of light, we see the grownup relearn to see with those baby-eyes that are awake to the luminous everythingness of everything, undulled by the accumulation of filters we call growing up. What emerges is a celebration of attention as affirmation of aliveness, a vibrant testament to Simone Weil’s exquisite observation that “attention is the rarest and purest form of generosity.” Page after painted page, a generous presence unfolds — presence with the new life of this small helpless observer of the world, presence with the ancient life of sky and sea.

BEFORE I GREW UP

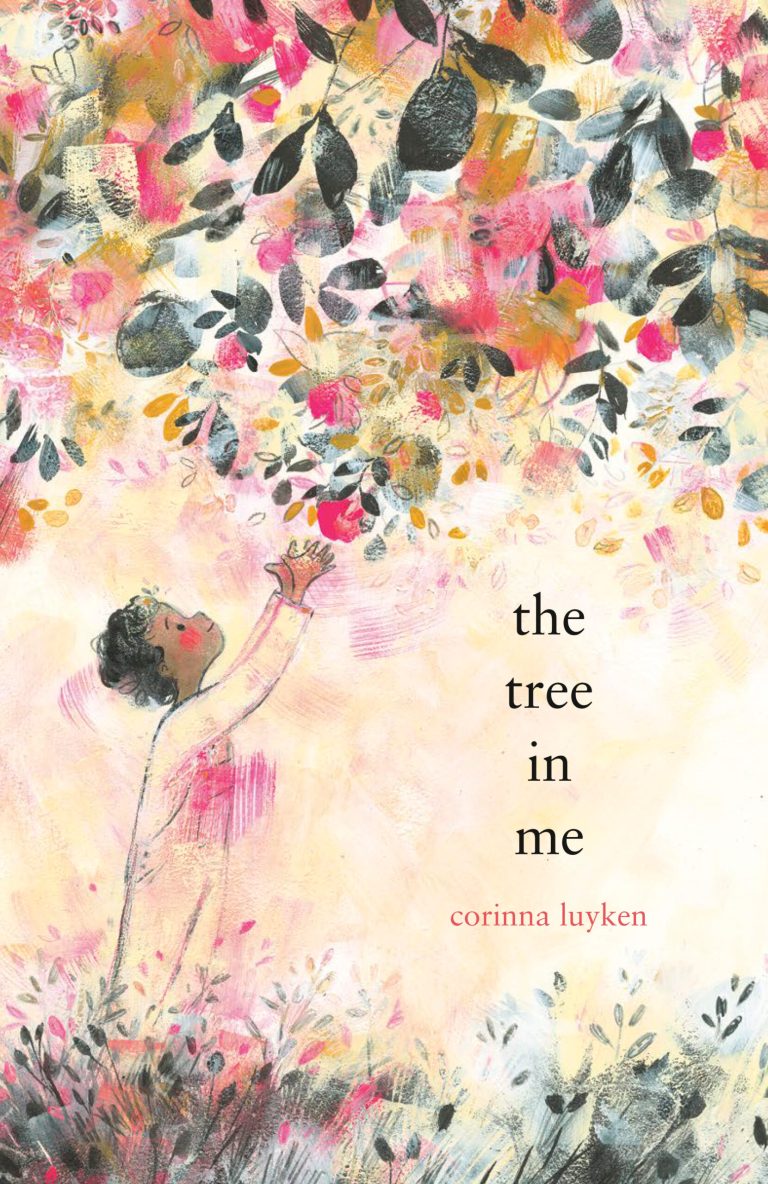

THE TREE IN ME

WHAT IS A RIVER

SEEKING AN AURORA

DARLING BABY

MAKE MEATBALLS SING

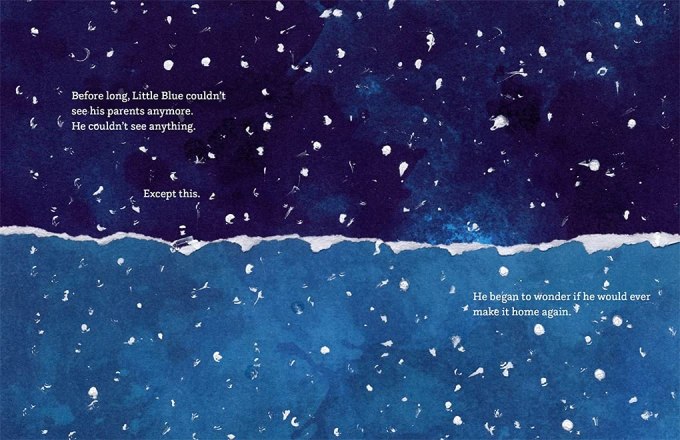

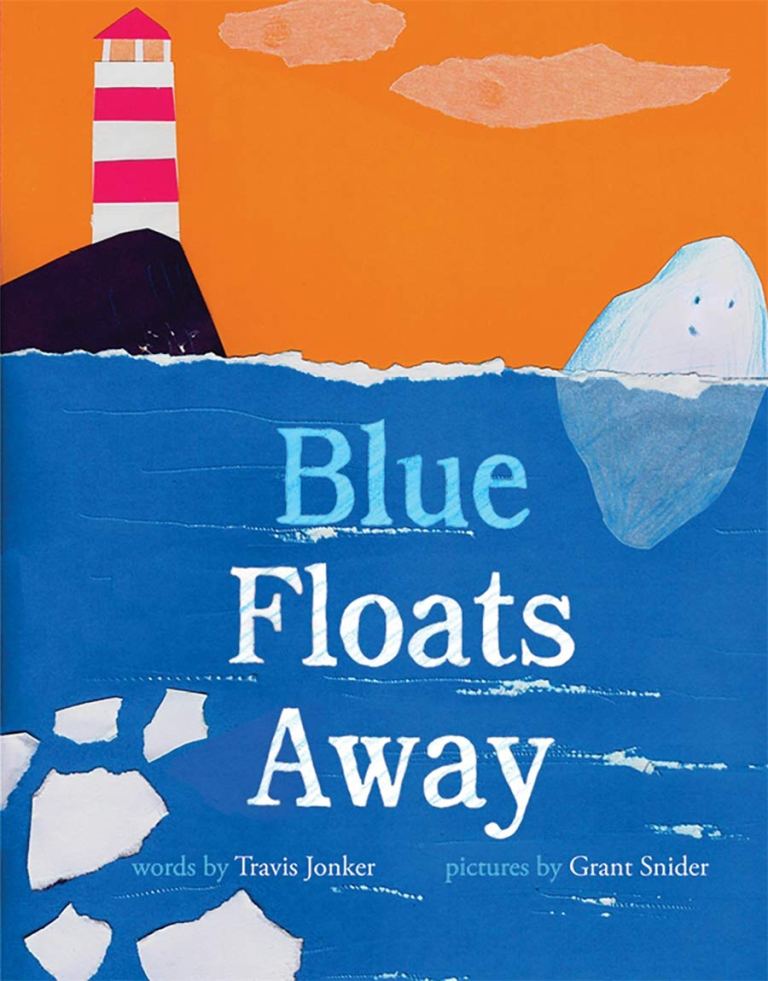

BLUE FLOATS AWAY

(AND FROM ME: THE SNAIL WITH THE RIGHT HEART)

While the story is inspired by a beloved young human in my own life, who is living with the same rare and wondrous variation of body as the real-life mollusk protagonist, it is a larger story about science and the poetry of existence, about time and chance, genetics and gender, love and death, evolution and infinity — concepts often too abstract for the human mind to fathom, often more accessible to the young imagination; concepts made fathomable in the concrete, finite life of one tiny, unusual creature dwelling in a pile of compost amid an English garden.

Peek inside here.

Artist and author Corinna Luyken draws on this intimate connection between the sylvan and the human in The Tree in Me (public library) — a lyrical meditation on the root of creativity, strength, and connection, with a spirit and sensibility kindred to her earlier emotional intelligence primer in the form of a painted poem.

If we are lucky enough, or perhaps lonely enough, we learn to reach out from this primal loneliness to other lonelinesses — Neruda’s hand through the fence, Kafka’s “hand outstretched in the darkness” — in that great gesture of connection we call art.

Hubble’s Law staggers the imagination with the awareness that even our most intimate celestial companion, the Moon, is slowly moving away from us every day, about as fast as your fingernails grow. This means that at some future point, the greatest cosmic spectacle visible from Earth will be no more, for a total solar eclipse is a function of the glorious accident that the Moon is at just the right distance for its shadow to cover the entire face of the Sun when passing before it from our vantage point — a shadow that will grow smaller and smaller as our satellite drifts farther and farther away. Before Hubble, the study of astronomy had already stunned the human mind with the awareness that this entire drama of life is a miracle of chance, unfolding on a common rocky planet tossed at just the right distance from its star to have the optimal temperature and optimal atmosphere for supporting life. Hubble sent the human mind spinning with the swirl of gratitude and terror at the awareness that it is all a temporary miracle.

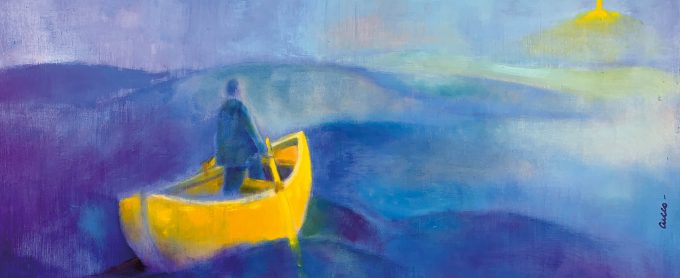

A river is a thread.

It embroiders our wold with beautiful patterns.

It connects people and places, past and present.

It stitches stories together.

Peek inside here.

Inspired by Thich Nhat Hanh’s timeless and transformative mindfulness teachings, which she first encountered long ago in the character-kiln of adolescence and which profoundly influenced her worldview as she matured, Luyken considers the book “a seedling off the tree” from the great Zen teacher’s classic tangerine meditation — the fruition of her longtime desire to make something beautiful and tender that invites the young (and not only the young) to look more deeply into the nature of the world, into their own nature and its magnificent interconnectedness to all of nature. After years of incubation, after many trials that landed far from her vision, a spare poem came to her. Paintings grew out of the words. A book blossomed.

And then I did: The Snail with the Right Heart: A True Story (public library) is a labor of love three years in the making, illustrated by the uncommonly talented and sensitive Ping Zhu, whom I asked for the honor after she staggered me with the painting that became the cover of A Velocity of Being: Letters to a Young Reader.

Rivers are the crucible of human civilization, pulsating with the might and mystery of water, their serpentine paths encoded with the precision of pi, their ceaseless flow encoded in our greatest poems.